Drawing a map of distributed data systems

Published by Martin Kleppmann on 15 Mar 2017.

How we created an illustrated guide to help you find your way through the data landscape.

Designing Data-Intensive Applications, the book I’ve been working on

for four years, is finally finished, and should be available in your favorite bookstore in the next

week or two. An incomplete beta (Early Release) edition has been available for the last 2½ years as

I continued working on the final chapters.

Throughout that process, we have been quietly working on a surprise. Something that has not been

part of any of the Early Releases of the book. In fact, something that I have never seen in any tech

book. And today we are excited to share it with you.

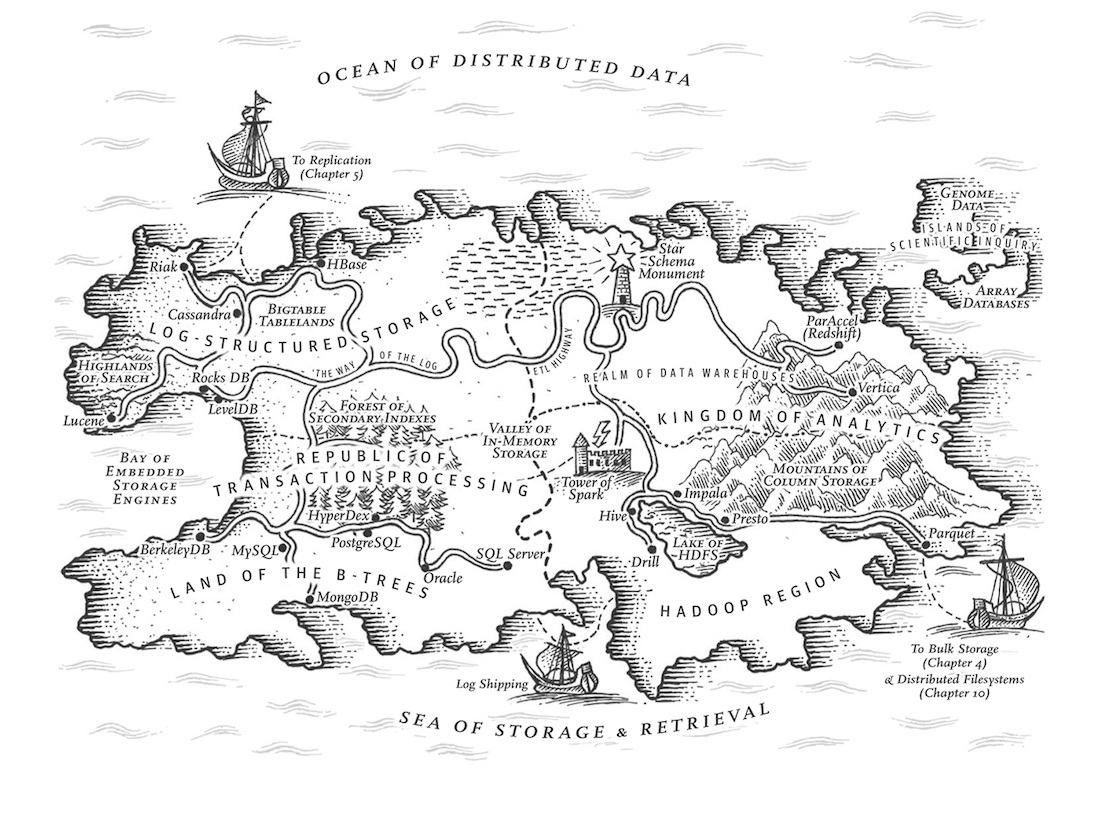

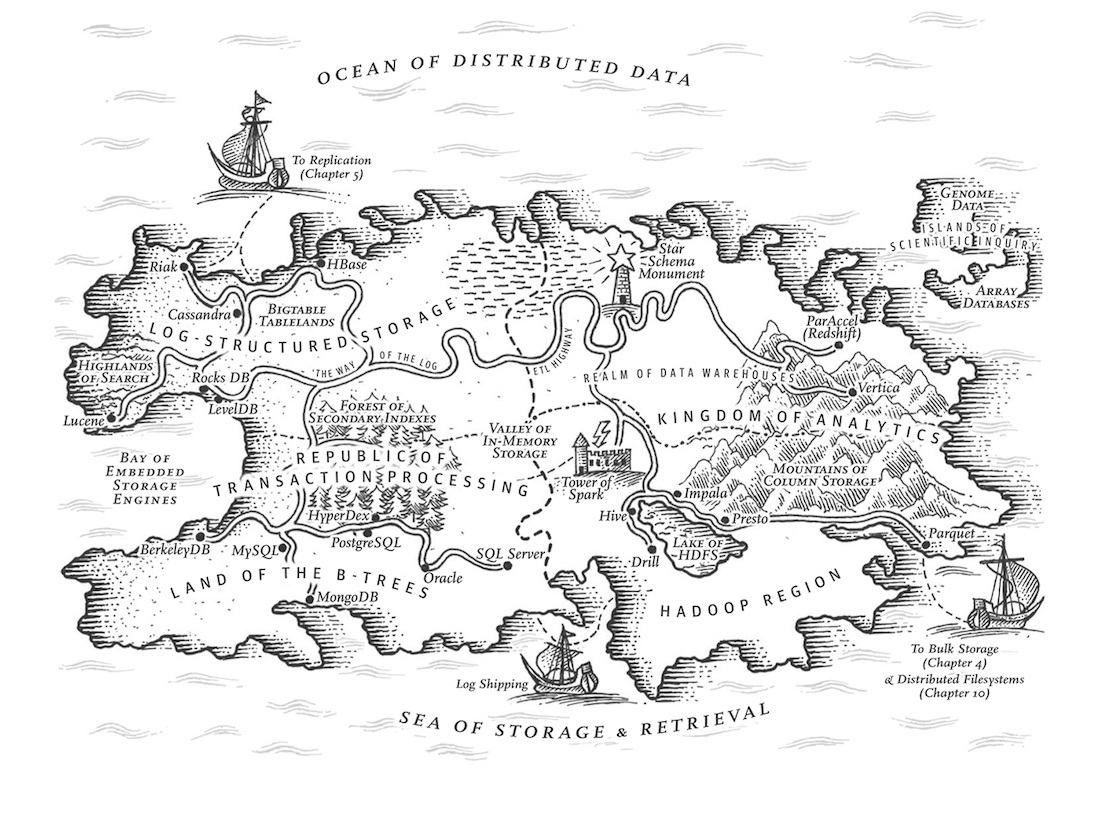

In Designing Data-Intensive Applications, each of the 12 chapters is accompanied by a map. The map

is a kind of graphical table of contents of the chapter, showing how some of the main ideas in the

chapter relate to each other.

Here is an example, from Chapter 3 (on storage engines):

Figure 1. Map illustration from Designing Data-Intensive Applications, O’Reilly Media, 2017.

Don’t take it too seriously—some of it is a little tongue-in-cheek, we have taken some artistic

license, and the things included on the map are not exhaustive.

But it does reflect the structure of the chapter: political or geographic regions represent ways of

doing something, and cities represent particular implementations of those approaches. Similar things

are more likely to be close together, and roads or rivers represent concepts that connect different

implementations or regions.

Most computing books describe one particular piece of software and discuss all the aspects of how it

works. This book is structured differently: it starts with the concepts—discussing the high-level

approaches of how you might solve some problem, and comparing the pros and cons of each—and then

points out which pieces of software use which approach. The maps use the same structure: the region

in which a city is located tells you what approach it uses.

For example, in the map above, you can see a high-level subdivision into two countries: transaction

processing and analytics. Within transaction processing, there are two regions: log-structured

storage and B-trees, which are two ways of implementing OLTP storage engines. Within the B-tree

region, you see databases like MySQL and PostgreSQL[1], while within

the log-structured region you see databases like Cassandra and HBase. On the analytics side, you can

see that the mountain range representing column storage reaches into both the data warehousing and

the Hadoop regions, since the approach applies to both.

The maps are in black and white, both because of practicalities of printing and also because I was

looking for a

Tolkien-esque style.

You are, of course, welcome to color them in yourself. In fact, by coloring them in, you would be

following a fine tradition: for over three centuries, maps were printed in black and white from an

engraved copper plate, and then colored in by hand.

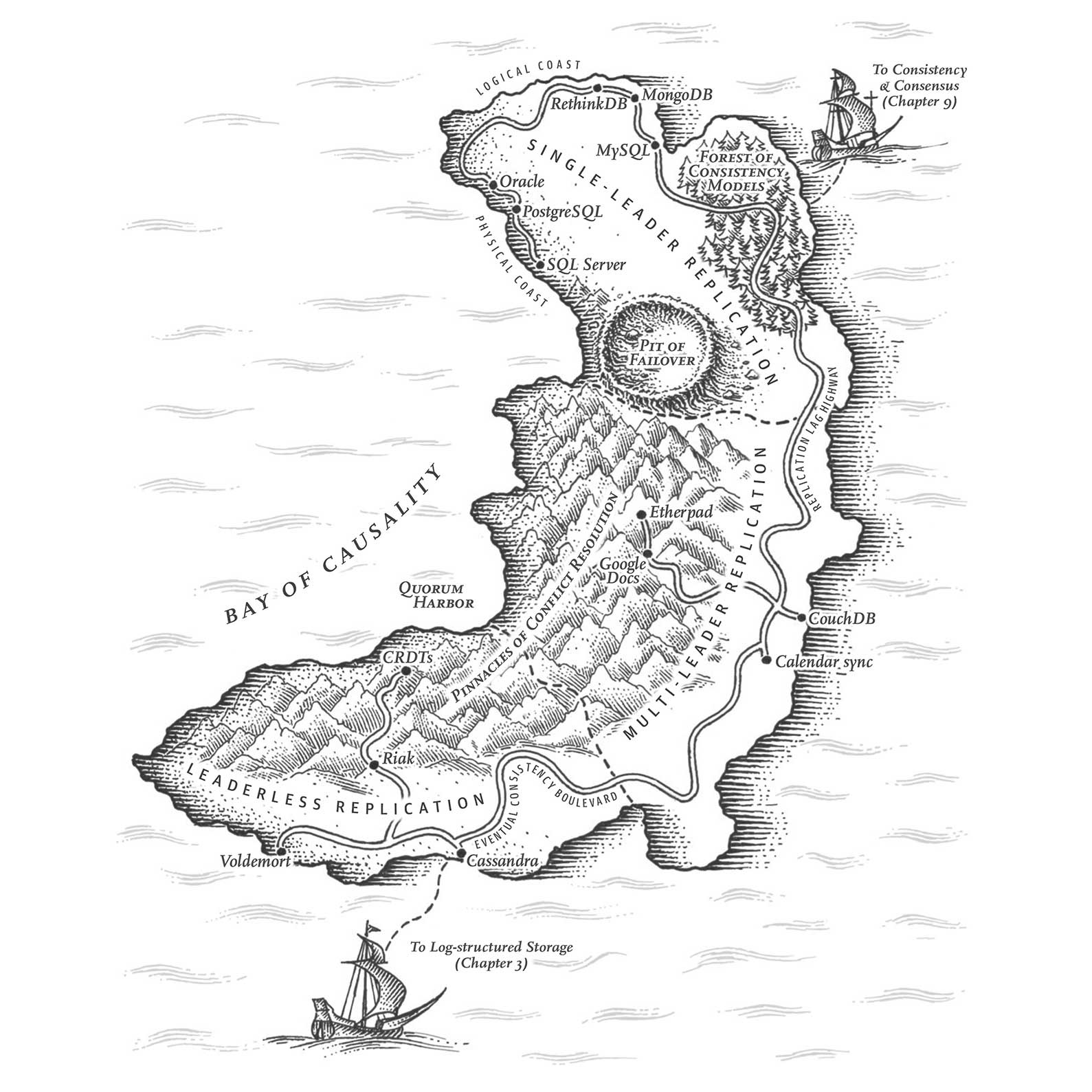

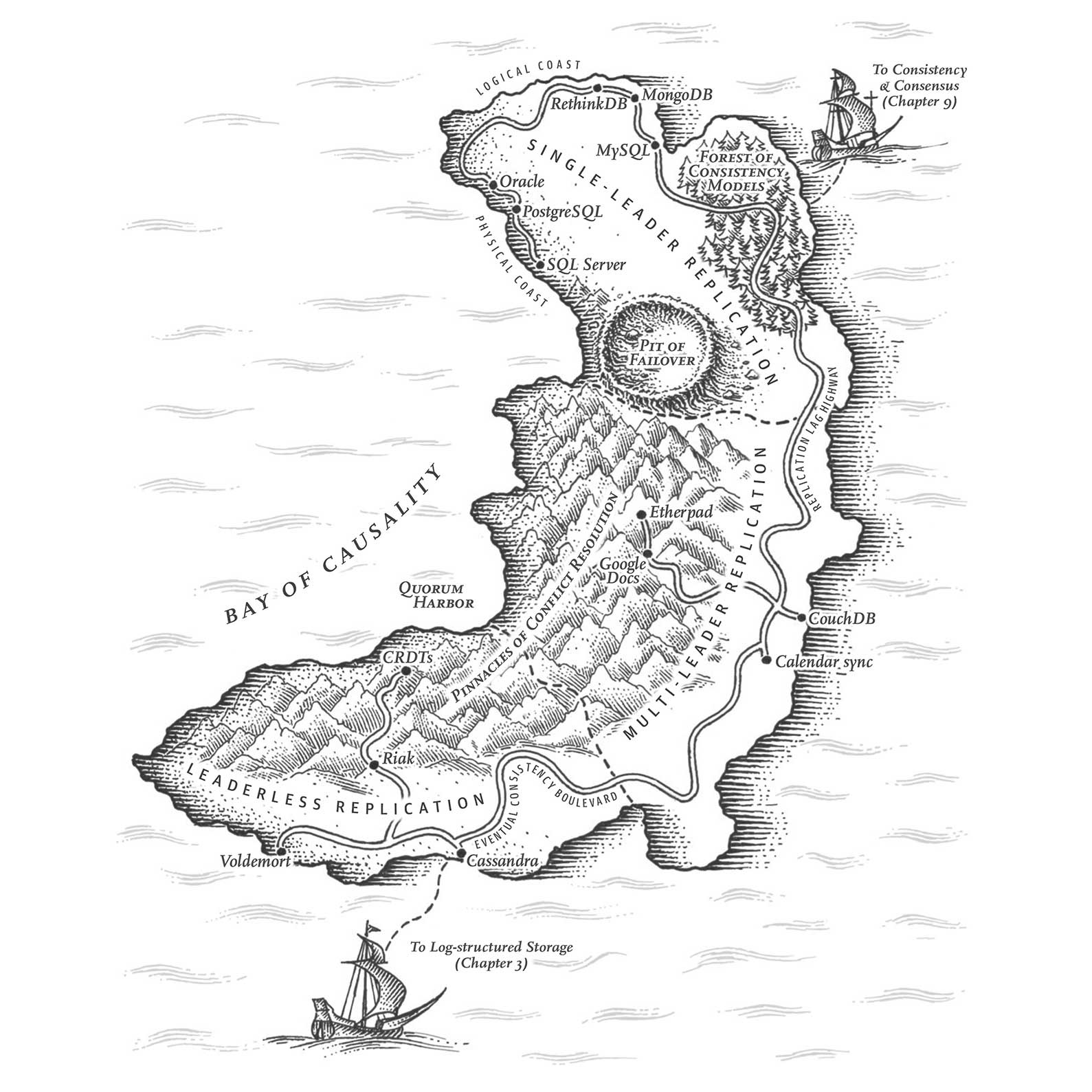

Each of the chapters has a map like that, focusing on the particular aspects discussed in that

chapter. This means that some cities appear on multiple islands—the data landscape is

multidimensional, so a city may lie in more than one (conceptual) realm. For example, the map below

is for Chapter 5 (on the topic of replication):

Figure 2. Map illustration from Designing Data-Intensive Applications, O’Reilly Media, 2017.

Cities representing Cassandra, MongoDB, MySQL, and others appear on both this map, the Chapter 3 map

above, and some other maps, too.

Shipping routes connect some of the ports shown in the maps, in cases where there is a noteworthy

link between chapters. Most of the maps are of islands, but there are some exceptions. (I won’t give

away too much, but I just want to say…beware of the

Kraken.)

I am incredibly delighted that O’Reilly was willing to take on this crazy idea of creating maps. It

took a whole team to make them happen: from my

rough pencil sketches (which

showed the structure but had absolutely zero artistic value),

Shabbir Diwan,

Edie Freedman, and Ron Bilodeau

created the beautifully illustrated versions you see above, and

Marie Beaugureau patiently managed several rounds of revisions, in

which we painstakingly polished all the details.

Perhaps you’re curious to know how we got onto the idea of creating maps. Early on in the Early

Release of the book, some readers told me they would love some kind of flowchart to help them decide

quickly which database they should use for their application. Such flowcharts

have been attempted,

but I never liked them much—it is tempting to read them out of context and jump to conclusions too

quickly, and they have to simplify the issues to the point of almost being intellectually dishonest.

My goal for Designing Data-Intensive Applications was different. I can’t in good faith give you

a recommendation for one particular tool because I don’t know enough about your particular

requirements. However, I can teach you what questions to ask and how to evaluate vendors’ claims

critically. That requires more subtlety and detail than can be expressed in a one-page flowchart,

which is why the book is 600 pages long, not one page.

However, I did think that some kind of graphical representation of the main ideas and structure

would be useful. I thought about Venn diagrams, but

they’re excruciatingly boring. I thought about mind maps,

and then started taking the “maps” bit more literally. I thought about the

Atlas of Experience by Louise

van Swaaij and Jean Klare, a sublime book that represents aspects of human life as fictitious

places on a geographic map.

(It is originally in Dutch;

the English translation is, sadly, out of print.)

The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton

Juster and Jules Feiffer does

a similar thing.

Closer to technology, similar map-style visualizations have been used to

represent online communities, to visualize the

history of relational databases and

programming languages, and to

explain libraries related to Facebook’s React.

I simply love the style.

Other inspirations for me are the ornate maps produced in the medieval and renaissance periods,

especially when it comes to whimsical

sea monsters.

For example, around 1590, Abraham Ortelius published a

wonderful map of Iceland,

with Mount Hekla spewing fire, and surrounded by fantastical

sea monsters:

Figure 3. “Islandia” map by Abraham Ortelius, ca. 1590. Source:

Wikimedia Commons

I feel those maps and sea monsters reflect the 16th-century sense of excitement to explore the earth

and discover new places, as well as the dangers of sailing across unknown seas. And perhaps a bit of

that excitement exists today in our exploration of technologies for storing, processing, and using

data. There seems to be a lot of potential, but we also don’t really know what we’re doing, and it’s

sometimes a bit dangerous (raise your hand if you’ve lost data at some point because something went

wrong).

We hope the maps in Designing Data-Intensive Applications will help convey some of that

excitement, and also make you smile. In both the print and ebook editions, the map for each chapter

appears at the start of each chapter.

What’s more, we have taken all the individual chapter maps and assembled them into a poster—an

archipelago of islands representing technologies in the sea of distributed data. The poster also

includes some bonus sea monsters (of course).

If you are at

Strata + Hadoop World, San Jose

this week, you can drop by the O’Reilly booth to pick up a free print of the poster so you have

something geeky and cool to hang on the wall in your office. Alternatively,

you can download a JPG version for free from the O’Reilly website

for your personal, noncommercial use.

We hope you enjoy Designing Data-Intensive Applications and the maps as much as we enjoyed making them!

Figure 4. Me holding the poster with the maps.

[1] Footnote for the well-actually

crowd: yes, I know about hash indexes and GiST in PostgreSQL, various other index types in other

databases, and the fact that in MySQL the index type is actually a matter of the storage engine

(such as InnoDB), but those details are beside the point here. I am highlighting a dichotomy between

a page-oriented update-in-place approach and a log-structured, compaction-based approach. This

distinction is best explained with concrete examples, and the graphical representation cannot

capture all the subtleties that are discussed in the text of the book.

If you found this post useful, please

support me on Patreon

so that I can write more like it!

To get notified when I write something new,

follow me on Bluesky or

Mastodon,

or enter your email address:

I won't give your address to anyone else, won't send you any spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.