Yes/No/Cancel causes Aspirin sales to soar

Published by Martin Kleppmann on 19 Jul 2007.

Welcome to Yes/No/Cancel, the online usability magazine. This first article describes the origin of

the name, and explains why it is bad to use buttons labelled Yes, No and Cancel in computer

programs. I also discuss why user-friendliness in general is a very important topic.

This online

magazine (or blog if you will) is about user-friendliness, and lack thereof. It criticises bad

design and promotes good design. One might think that after usability research has been conducted

for many years and many books have been written on the topic, finally people would have learnt to

get it right. But no – my impression is that many products are as bad as ever, and the reason why I

am writing this is to raise awareness of these problems.

But why should you care? As a user, you

should care because you have a choice – you can stop using/buying the product that is not friendly

to use. You can switch to a better one, saving you frustration and annoyance. As a manufacturer, you

should care for much the same reason – you are in a competitive environment, and if you don’t

carefully consider the needs of your customers, you will see them leaving very soon!

Maybe you ask

how this website got its name. Yes/No/Cancel, that sounds like computers. Yes, and a lot of the

content here (but definitely not all) is going to be about computer software. Today, many pieces of

software are amongst the most complex pieces of engineering which the human mind has devised. It is

therefore not too surprising that some software packages are extremely difficult to use. But

software is also used by many people every day who don’t want to know about this complexity. Is

difficulty of use really necessary? There are some examples of extremely complex systems which are

absolutely straightforward to interact with (Google search for example –

it’s the work of a big team of the world’s best software engineers over several years, and still

it’s just a simple search box).

Making complicated systems easy to use is actually quite a

difficult problem. Part of the problem is that the engineers designing the system are often used to

a certain way of doing things, but this way is not always best adapted to a particular situation or

audience. The designers and developers of a system must therefore constantly be questioning their

habits, so that they can find better ways of solving problems if better ways exist.

One particular

bad habit of programmers annoys me so much that I decided to name this website after it.

Johannes suggested the name: Yes/No/Cancel. The choice you are so

often presented with in many computer applications, and so often you have to stop and think, because

it’s not immediately clear what each of the choices is actually going to do. Which one of the

buttons will cause all your work to be lost if you press it? Which one will save it? And what does

Cancel mean anyway? Aaargh, it causes headaches.

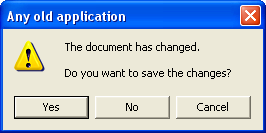

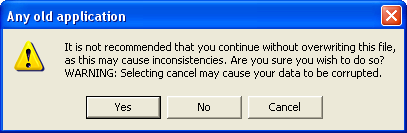

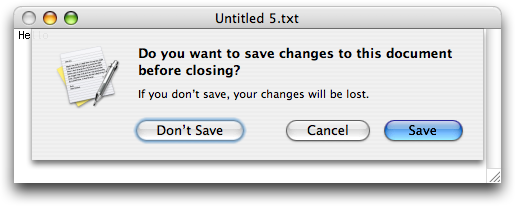

Let me explain this with a few examples. A

situation in which you frequently encounter a Yes/No/Cancel dialog box is when you are trying to

close a document without having saved it. Like

this:

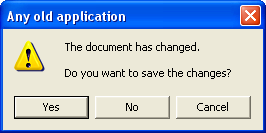

Nice of it to ask, you say – you had completely forgotten to save. Ok. Now

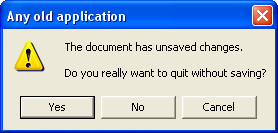

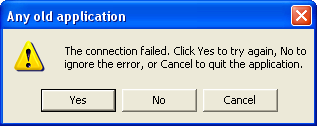

compare it to this one:

Can you believe it? It’s asking the opposite question! Now even if you

usually know by habit which button to press, suddenly you have to stop and think. And this box is

even worse, because it’s not clear what the difference is between No and Cancel.

Fundamentally the problem here is that we are actually asking two questions at the same time:

- Do you want to save the document?

- Do you want to quit the application?

The answer to each question might be yes or no, which gives us four different possible actions:

- save changes and quit (the “Yes” button in the first example)

- discard changes and quit (the “No” button in the first example)

- do nothing – do not save and do not quit (the “Cancel” button in the first example)

- save changes but do not quit

The fourth option is generally perceived

to be silly, so there is no button for that purpose and we get a choice of three. In the first

example picture, these three correspond to Yes, No and Cancel respectively. What about the second

example? Clicking Yes will “discard changes and quit”. Maybe clicking No will save changes and quit,

or maybe it will do nothing. Who knows what cancel will do, let alone the mystery of the red X in

the corner.

Already with simple examples like this, you can begin to see that it’s a bad idea to

label buttons as Yes, No and Cancel. The meaning of these words depends very much on the question.

In fact, if you have no previous computing experience, you will probably have no idea what to

answer. As a user, you just want to know which button is going to cause your work of the last 2

hours to be lost – and neither of these examples makes it immediately clear which the “dangerous”

button is.

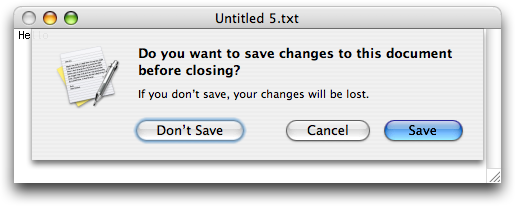

Apple have tried to avoid this problem by not labelling the buttons Yes/No/Cancel, but

more descriptively:

Using a verb (in this case “save”) is recommended in Apple’s

Human Interface Guidelines.

Also note that the “dangerous” button (which discards changes and quits) is set apart from the two

“safe” buttons. This is clearly much better already, but the program is still trying to answer two

questions at the same time, which you may consider to be an unnecessary complication.</p>

I won’t dwell

on any Microsoft vs. Apple discussion though, because what I am saying applies not just to these two

companies, but also to every other organisation or person who writes software. And there are some

terrible occurrences of Yes/No/Cancel in the world for which neither Microsoft nor Apple carries any

blame.

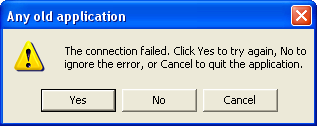

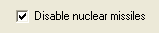

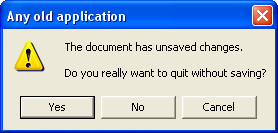

One terrible thing which you see sometimes is an implicit relabelling of the buttons. Here

the programmer clearly couldn’t be bothered to make his own buttons, and instead placed the burden

on the user:

You really need to switch

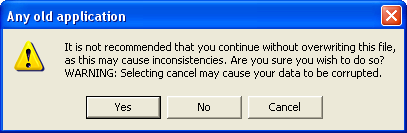

on your brain to decide which button to press. And by phrasing the question badly, it can get even

worse:

At this point, I very much hope that you will have run out

of the room screaming. And maybe returned to read the rest of this article. (With a headache.)

You might think that the last example was very contrived, but the point I wanted to make was about

negative questions. Why ask whether not to do something (the negative) if you can simply ask whether

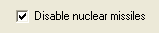

to do something (the positive)? I find this occurring particularly frequently with respect to

checkboxes:

It is counterintuitive to put a tick in a box for something you don’t want. Just don’t ask negative

questions. But that’s a story for another day.

A few final remarks:

If you found this post useful, please

support me on Patreon

so that I can write more like it!

To get notified when I write something new,

follow me on Bluesky or

Mastodon,

or enter your email address:

I won't give your address to anyone else, won't send you any spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.