Book Review: The Future of Fusion Energy

Published by Martin Kleppmann on 03 Jan 2022.

I give a five-star ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ rating to the following book:

Jason Parisi and Justin Ball. The Future of Fusion Energy. World Scientific, 2019. ISBN 978-1-78634-749-7. Available from Amazon US, Amazon UK, and many other retailers.

I came to this book looking for answers to questions such as: Is there still hope that a fusion power plant will ever be viable? If so, what exactly are the main obstacles on the way there? Why has progress in this field been so slow? And what should I make of the various startups claiming to have a fusion power plant just round the corner?

The book provides an excellent, detailed answer to these questions, and more. It’s the best kind of popular science book: you don’t need a physics degree to read it, but it doesn’t fob you off with oversimplified hand-waving either; all of the core arguments are convincingly backed up with evidence. There are some equations, but they are not necessary for understanding the book: as long as you know the difference between an electron, a proton, and a neutron, you’ll be able to follow it.

The book is clear about which constraints on fusion energy are fundamental limits of nature, and which constraints can be overcome with better technology. It offers optimism that fusion power is possible, highlighting the most promising paths to getting there, while remaining honest about the open problems that are yet to be solved. My take-away was that core problems, such as plasma turbulence, are very difficult, but likely solvable with more brainpower and experiments.

The book also provides compelling arguments in favour of fusion: not only the obvious case of providing cheap energy without carbon emissions or seasonal variation, but also that compared to fission, there is much less risk that the technology will facilitate the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

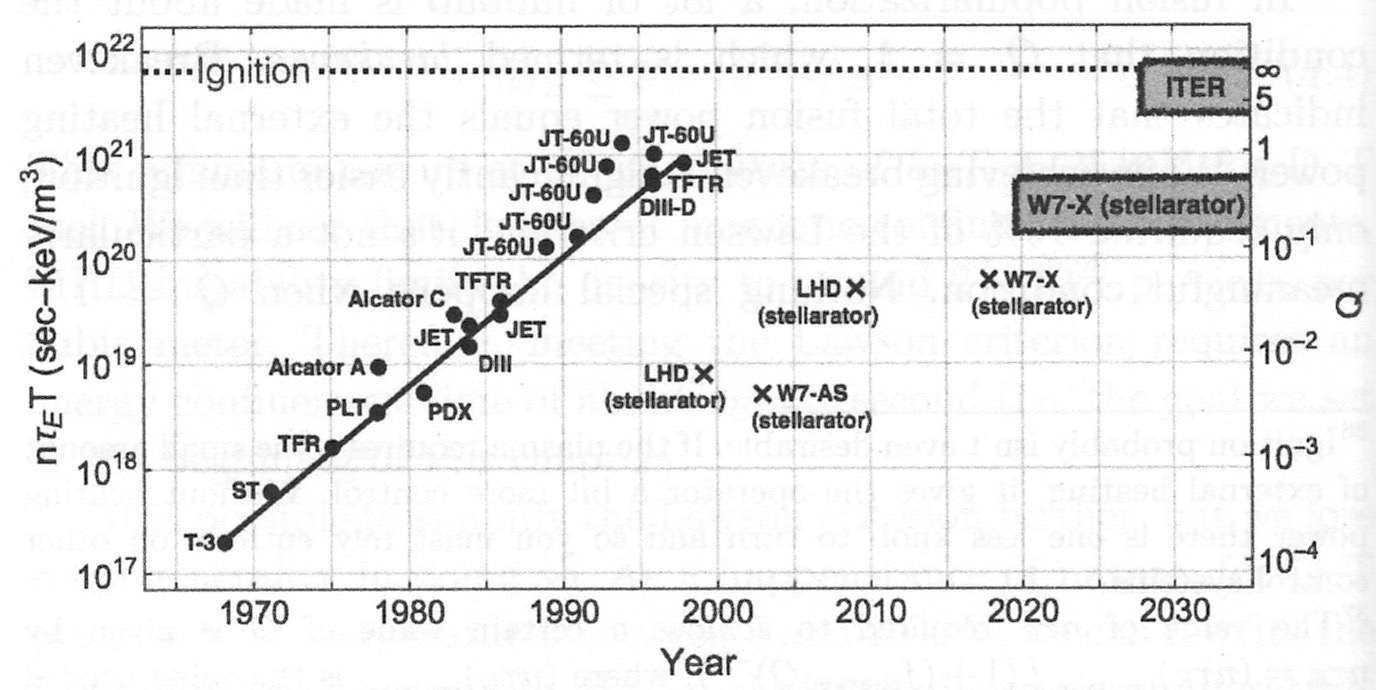

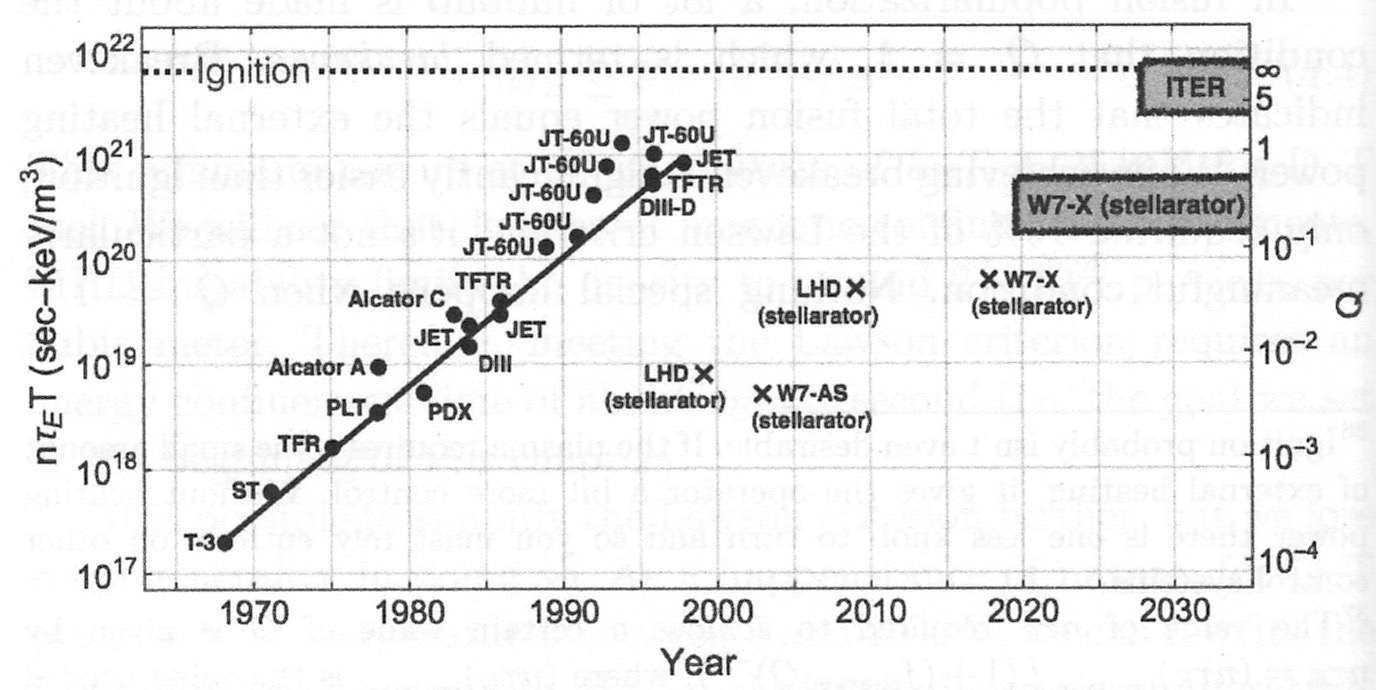

The need to transition away from fossil fuels is so urgent that we can’t afford to wait for fusion — renewables and fission are still crucial. However, for the medium to long term, fusion offers optimism. From about 1970 to 2000, fusion research made very impressive progress, with the key performance metric doubling every 1.8 years — faster even than Moore’s law, and getting pretty close to the point where the fusion reaction is self-sustaining without having to continually feed in external energy (the dotted line labelled “ignition” on the following diagram)!

Figure 4.25 from the book. Note the log scale on the y axis, so the straight line from 1970 to 2000 is actually exponential growth.

Since 2000, progress has stalled, and the book argues that this is primarily because research in the field has been under-funded, not because of any particular fundamental limit. Of course, anybody can claim that more money will solve their problems, but in this case I’m inclined to believe it. What changed in 2000 is that the fusion research community started putting all their eggs in one basket (ITER), because there wasn’t the money for multiple baskets. More money would allow more parallel experiments to explore different approaches and see which ones work better.

Investment in fusion research is small compared with investment in renewables and fission R&D, and tiny compared to things like agricultural and fossil fuel subsidies. Even if it’s not guaranteed that fusion will work, given the potentially transformative nature of cheap, climate-friendly energy to human civilisation, it seems well worth putting some more money in it and giving it our best shot (in addition to faster ways of getting off fossil fuels, such as renewables, of course).

I won’t try to summarise the technical details of the book, but if you are interested in them, I can assure you that you will find this book worthwhile.

If you found this post useful, please

support me on Patreon

so that I can write more like it!

To get notified when I write something new,

follow me on Bluesky or

Mastodon,

or enter your email address:

I won't give your address to anyone else, won't send you any spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.