How to negotiate a price: Return on Indignation

Published by Martin Kleppmann on 30 Jan 2010.

As an entrepreneur you have to negotiate things: customer contracts, freelance rates, investments,

acquisitions and more. These things are really important, but you probably grew up in a western

country where you buy the bar of chocolate for the price it says on the shelf, no more and no less.

We’re not used to negotiating things. So how do you determine a good price?

I’m sure much has been

written about this already, but I’ve not really read any of it. Instead I made up some principles

based on my own bit of experience and a bit of common sense, and maybe you will find them

useful.

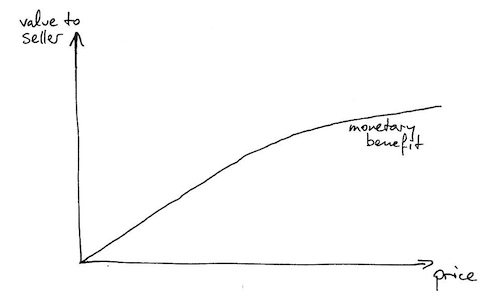

So let’s take a look at a negotiation from the point of view of the seller. When you’re

selling something, you want to charge as much as you can get away with. The higher the price, the

better for you, i.e. the higher the monetary benefit of the sale to

you.

The first bit of money makes a big difference –

maybe you really need it so that you can pay the rent, otherwise you’ll get kicked out of your

house. Within this range, having more money is clearly a lot more valuable for you. However, as the

amounts increase and you have secured an acceptable standard of living, I would argue that the

benefit of the money to you slows down. Frankly, a top-paid investment banker would barely

notice the difference if their salary or bonus was increased or decreased by 50%.

But nevertheless,

although it gradually flattens a bit, the line is always increasing. If you can get more out of a

deal, it’s a better deal. At first glance anyway.

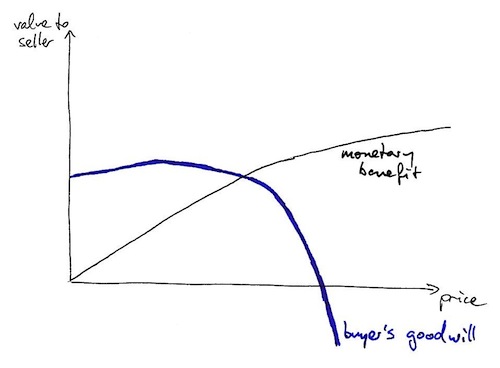

However, that’s not the end of the story. When I

am negotiating with someone, this is usually someone I actually want to work with, and I want to

stay friends with them. You don’t want to charge so much that they will simply walk away. And if

you’re in a strong position where the buyer doesn’t have much choice (eg. because it’s something

urgent and they don’t have time to find someone else), you don’t want to abuse your position, as

otherwise you will get a bad reputation as someone who takes advantage of others.

Therefore, you

should be taking your relationship with the buyer into account. How indignant they will be about

your price will depend on a lot of factors (the market value of what you have to offer, how much you

charged them previously, how much they can afford, etc). But in general there will be some sort of

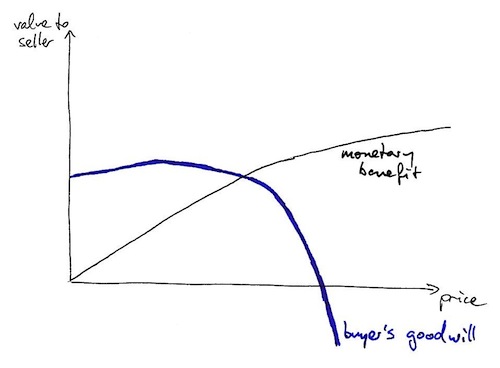

function describing how happy they are depending on the price (BogoGraph alert!):

Here I plotted in blue the buyer’s “goodwill” (not in

any financial sense, just in the sense of “how much they like you”). If you charge too much, they

will obviously hate you, so the graph goes downhill very rapidly beyond a certain point. You

probably don’t want to go there. I think it is also possible to charge too little, which conveys the

message that what you have is not particularly good and not worth very much; but that won’t offend

your buyer nearly as much as overcharging them. So I’d say that the graph first goes up a little

bit, and then goes down a lot.

How do you figure out the shape of that curve for your buyer? That’s

hard. You need to get a few data points, for example you might try asking them for a pretty high

price and observing how upset they get. But you’ve got to be very careful – don’t abuse their trust

and don’t waste their time. The longer you spend trying to measure the blue curve, the lower it gets

overall (i.e. the more irritated they get with you). It’s better if you can use external things as

reference points – how much an alternative solution would cost them, how much they have paid for

comparable things in the past, the size of their budget (which they probably won’t tell you but you

might be able to guess indirectly).

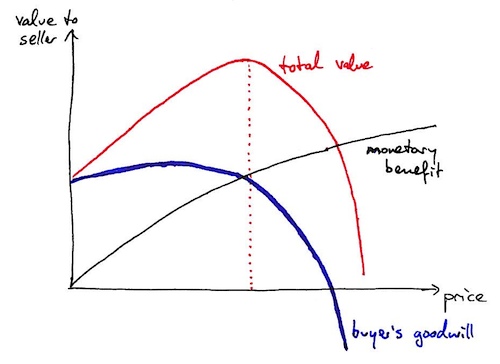

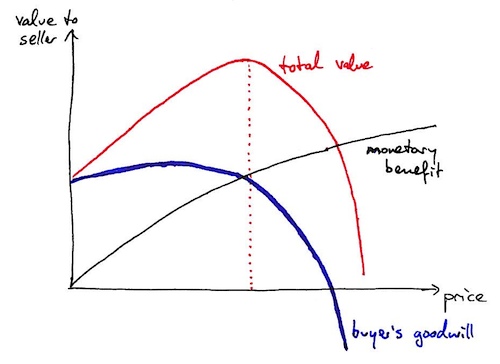

The value you get out of making the sale is twofold: on the one

side the money you get out of it, and on the other side the buyer’s goodwill (with all of its

intangible benefits, such as keeping open potential future deals, recommendations, referrals,

general happiness and warm fuzzy feelings). You want both, so let’s just add the two curves

together:

The red line is simply the sum of the blue and the

black, and represents the total value you’re getting out of the sale. Some things to

observe:

- There is a very clear maximum for the total value. This is what you should be aiming at.

- The price at which the seller’s value is maximised is always higher than the ideal

price for the buyer (i.e. the red line’s maximum is further to the right than the blue line’s

maximum). Of course the buyer would prefer to pay less – if that is not the case, you’re definitely

charging too little.

- The blue graph is like quantum mechanics: it changes when you measure it. Keep your

negotiations short, simple and clear. Don’t keep changing your mind, because that just reduces

goodwill and thus the total value. Keep in mind that the whole point of this exercise is to stay friends!

- The optimal price depends on your weighting of blue curve vs. black curve – the

less you care about the buyer’s goodwill, the higher the optimal price.

- Even if you are playing hard-nosed, it’s a game of diminishing returns. By pushing

harder you will get a bit more money, but the buyer will also get a lot more indignant. The harder

you push, the smaller your marginal gains.

This brings us to an interesting concept: you

can trade in buyer’s goodwill for more money by adjusting how much you care about how the other

party feels. There is a return on the indignation of the other party, and it’s up to you to

choose what you want this return to be.

It depends on your character and on the strategic value of

the particular deal. I generally work with quite a low return on indignation, i.e. I value goodwill

quite highly and won’t readily trade it for a bit more money. That’s

because:

- I don’t find it fun to be hard-nosed, so I’ll much rather be nice (assuming the

other party is also nice), and

- I think in terms of long-term value, and I believe that goodwill stays around for a

long time, so I’ll much rather invest in building good long-term relationships than try to extract

the maximum monetary value in the short term.

That’s my approach, and I’m sure others will think differently. But at least, with a framework

like this, you can be conscious about your return on indignation.

By the way, if you’re into pricing products which are not individually

negotiated – quite a different topic – you should definitely read

Don’t just roll the dice by

Neil Davidson.

If you found this post useful, please

support me on Patreon

so that I can write more like it!

To get notified when I write something new,

follow me on Bluesky or

Mastodon,

or enter your email address:

I won't give your address to anyone else, won't send you any spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.