Valuation caps on convertible notes, explained with graphs

Published by Martin Kleppmann on 05 May 2010.

When you’re an entrepreneur out to raise funding, you’re faced with a whole lot of legal and

financial jargon, and getting your head around it takes a lot of valuable time – that’s time in

which you’re not doing the things which really matter (namely making your product better, making

your existing customers happy and acquiring new customers).

But actually, if explained properly,

most of the legal and financial stuff isn’t that complicated. The legal documents do a terrible job

of explaining, because they define everything in legalese prose. Graphs make it much clearer, as Leo

Dirac has shown in his wonderful

graphical explanation of liquidation preferences.

You should go and look at that presentation.

I’d like to explain a different financial concept, namely the

valuation cap on convertible notes. It took me several hours to get my head around it, so I’d

like to save you those hours.

The pros and cons of convertible notes

I assume you know what a

convertible note (aka convertible loan) is: instead of buying shares in your startup, the investor

just gives you the money on a loan with some nominal interest rate. And you promise that when you

raise your next round of funding, the loan converts into shares as if they had put that money in

during that second round. Since the investor took additional risk by backing you early, they get a

discounted share price (they get more shares than someone who puts in the same amount of money in

the second round), and that discount is fixed and agreed upon beforehand. It’s typically between

about 15% and 30%.

The good thing about convertible notes is that they require less paperwork (and

are thus faster to get done), and – in theory – don’t require you to set a valuation, because the

share price will be determined in the next round. However, many investors don’t like them. If the

company is really successful (as everybody hopes it will be) and the valuation in the next round is

high, then the investors don’t get any of that increase in value – they just get their fixed

discount, and that’s it.

With some

big-name investors, the company’s value goes up

simply by being associated with the big name. Naturally, the investor will also want to benefit from

that increase in value, because otherwise there’s not much incentive for them to help.

Enter the valuation cap, which appears to now be a standard term of convertible notes, in Silicon Valley at

least. The cap is the convertible note investor basically saying: “If things go ok, I’m happy with

my fixed 20% discount. But if you do really well, I want us to treat it as if I had bought shares in

the first place.” (That way they benefit more from the success.)

So you went for a convertible note hoping that you wouldn’t have to set a valuation for your startup.

Well, with the valuation cap you don’t strictly have a valuation, but you do have a range of valuations:

the company is certainly not worth less than X, and not worth more than Y.

In effect, someone has now got to

decide on a valuation, which is a notoriously unscientific thing. How do you come up with reasonable

numbers? You need to somehow build an intuition for what this stuff means.

How to determine your valuation cap

The best way to think about it is to start with some guesswork numbers, consider a

range of different scenarios, and work out the consequences. Then you can decide which consequences

are unacceptable, and work backwards.

Let’s work through an example. Say you’re a small startup

team raising your first seed round, and you expect to raise a Series A from VCs sometime in future.

Your input variables are:

- the amount you’re raising on the convertible note (say $500k),

- the conversion discount of the note (say 20%),

- the pre-money valuation cap of the note (say $4m),

- the percentage of your company which the VCs will take in your Series A (say 30%),

- the amount of money you expect to raise in your Series A (say somewhere between $1m and $5m).

There are a few other parameters (like the interest rate on the loan, and the

time between the seed round and the series A), but they ought to have only a minor impact.

The biggest unknown here is the amount you’ll want to raise in your Series A, so let’s look at a

range of scenarios for that value, and take the other variables to be fixed.

There are two consequences of the numbers which are useful to think about:

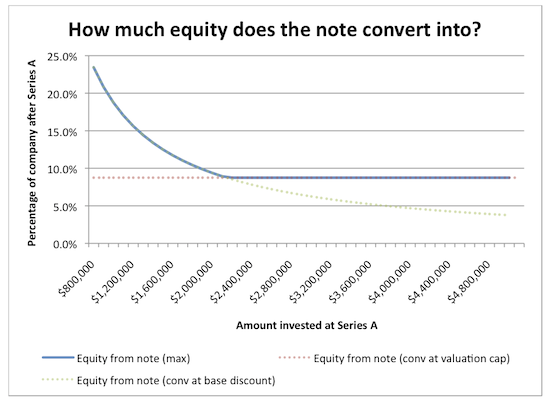

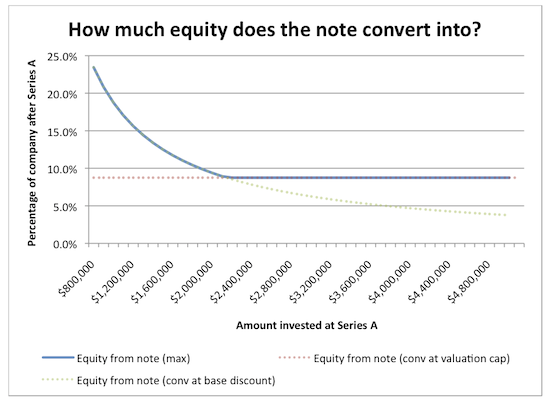

1. What share of the company do the convertible note investors own after the Series A?

We assumed above that after the Series A, the Series A investors own 30% of the company.

But how much do the seed investors own after converting their note into shares?

Without the valuation cap, the seed investors end up with an ever diminishing share of the company as the

valuation increases. The effect of the cap is that the convertible note investors are guaranteed a

certain share of the company, even if you get a

Foursquare valuation.

That minimum share is:

(1 – [series A investor ownership] ) * [amount raised on conv note] / [valuation cap].

(The first factor takes into account the Series A dilution.) In this example, the

note will convert into a minimum of (1–0.3) * $0.5m / $4m = 8.75% of the company’s shares.

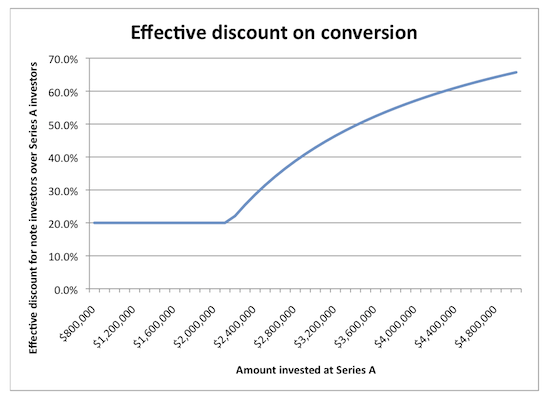

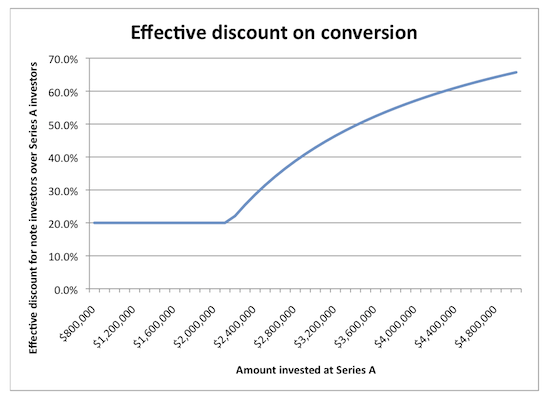

2. What effective discount are the convertible note investors getting relative to the Series A investors?

If you didn’t have a cap, you would simply give a fixed (say 20%) discount when the

note converts into shares. But when you have a cap, and your Series A valuation hits the cap, you’re

fixing the price for the early investors, while the incoming Series A investors might be paying a

lot more per share. So you are effectively giving a greater than 20% discount in that case.

I find this graph interesting, because it’s basically a measure of “how annoyed the VCs are going to be about

the convertible note”. – Imagine you’re at the theatre, and you know that for the same ticket you

paid 2 or even 3 times as much as the guy sitting next to you. You would not be happy, because it

just doesn’t feel fair. If your valuation goes substantially above the cap, there can be a big

difference in share price.

Of course, if your startup is awesome and investors are desperate to be

part of your round, this probably won’t be an issue. And of course, maybe such a large discount is

entirely fair if your Angel investors add a lot of value beyond the money they put in. But it’s a

factor to keep in mind. At least with a graph like this you can start thinking about your numbers

usefully.

Postscript

None of this gives you an immediate answer to the question “what should

we write on our convertible note term sheet?”, but at least you should now be able to think about

valuation caps from a few different angles.

Disclaimer: neither am I a lawyer nor do I have much

experience with this stuff, so my explanation may be horribly flawed or simply wrong. (If you find a

mistake, please let me know.)

You can download the Excel spreadsheet

which I used to generate these graphs. An interesting alternative way of looking at this would be to

assume a fixed Series A amount, and instead work out what happens when you vary the valuation cap.

I’ll leave that as an exercise for you, dear reader.

Incidentally, our awesome startup,

Rapportive, is raising a seed round at the moment. It’s filling up quickly,

so please

get in touch soon if you may be interested. The terms may have

certain similarities with my example here, or they may not – I couldn’t say. ;-)

Update (11 June 2010): Packed the Excel spreadsheet in a ZIP file to fix download problems.

Update (23 August 2011): Daniel Odio has made this into a

Google Docs spreadsheet – you can just fill in

your numbers and see the results immediately. Awesome!

If you found this post useful, please

support me on Patreon

so that I can write more like it!

To get notified when I write something new,

follow me on Bluesky or

Mastodon,

or enter your email address:

I won't give your address to anyone else, won't send you any spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.