Accounting for Computer Scientists

Published by Martin Kleppmann on 07 Mar 2011.

Every educated person really ought to have a basic understanding of accounting. Just like

maths, science, programming, music, literature, history, etc., it’s one of those things

which helps you make sense of the world. Although dealing with money is not much fun, it’s

an unavoidable part of life, so you might as well take a few minutes to understand it.

Sadly, in my opinion, most accountants do a terrible job of explaining their work in an

accessible way; it’s a field full of jargon, acronyms and weird historical legacies. Even

“Bookkeeping for Dummies” makes my head spin. Surely this stuff can’t be that difficult?

(We computing people are probably guilty of the same offence of bad explanations and jargon.

The problem is, once you have become intimately familiar with a field, it’s very hard to

imagine how you thought about things before you understood it.)

Eventually I figured it out: basic accounting is just graph theory. The traditional ways

of representing financial information hide that structure astonishingly well, but once I

had figured out that it was just a graph, it suddenly all made sense.

I’m a computer scientist, and I think of stuff in graphs all the time. If only someone had

explained it like that in the first place! It would have saved me so much confusion. So I

want to try to fix that. If you like graphs, then by the time you reach the end of this

article, you should know everything you need in order to understand the financial statements

for a small company/startup (and even calculate them yourself, in a spreadsheet or

programming language of your choice).

It’s really not that hard. Let’s go!

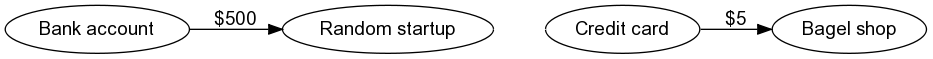

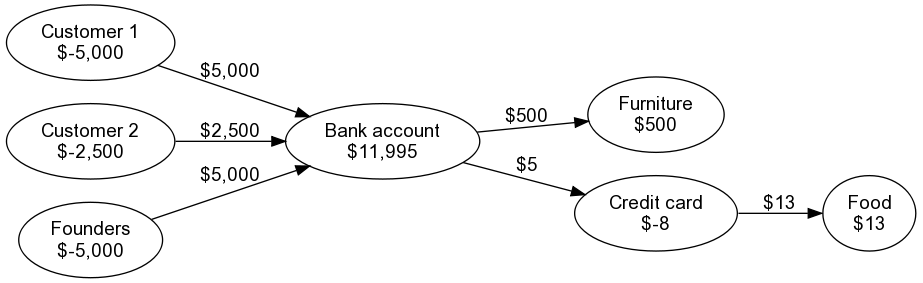

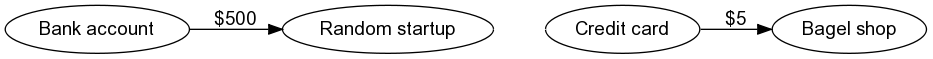

Accounts = Nodes, Transactions = Edges

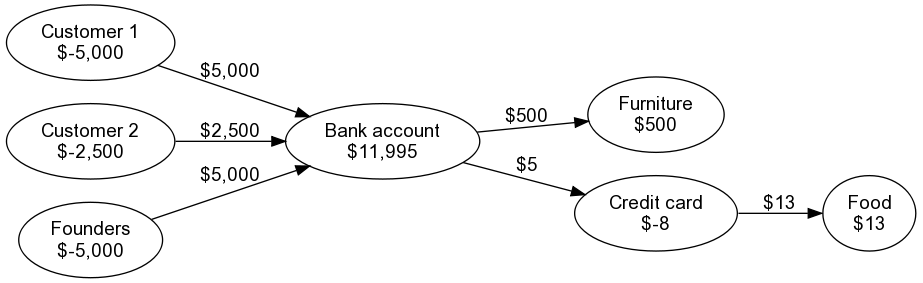

Say you go to the bagel shop and buy a Super Club bagel for $5 on the company credit card.

You also visit some random Silicon Valley startup and buy one of their surplus Aeron chairs, second

hand, for $500 (by writing a cheque from the company account). Those are two transactions.

Each transaction is an edge in our graph, and the edge is labelled with the amount.

An edge always goes from one node to another. What are those nodes? Well, you can define

them as you like (although there are some conventions). For now, let’s say:

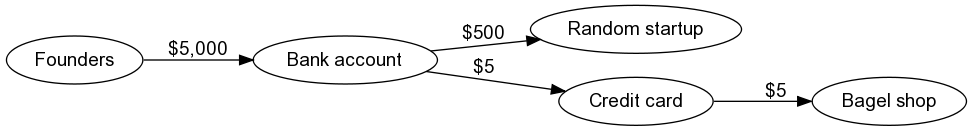

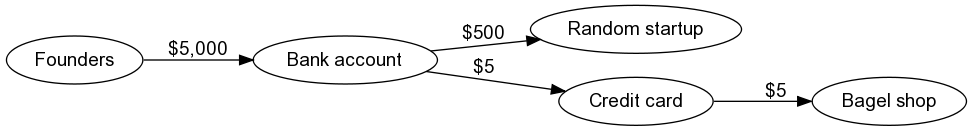

Let’s add some more details. You pay the $5 credit card bill from the company account. And where

did the money in the company account come from in the first place? Ah, I see, you

put in $5,000 of your savings to start the company. Ok, now the graph looks like this:

Hopefully pretty self-explanatory so far. Money flows in the direction of the arrows.

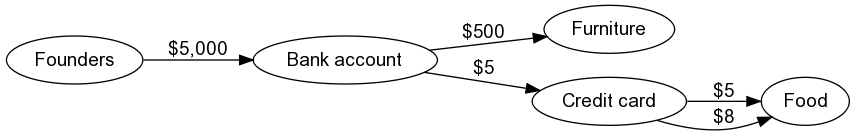

Hungry once again, you go to the taqueria and buy a Super Burrito for $8 on the credit card.

Now we could create another node for the taqueria, but this is starting to get messy – we

don’t really care how much money we spent on bagels vs. how much on burritos. Let’s just

lump them together as “food”. Also, “Random startup” is a bit unhelpful – I’ve already

forgotten what those $500 were for. Let’s call it “furniture” instead.

See, that’s perfectly fine. We can have nodes which represent actual bank accounts or cards,

others which represent people or companies, and others again which represent abstract

categories like “food” or “furniture”. Just throw it all into the same graph.

Note also that you can have several edges between the same pair of nodes. You can keep track

of the individual edges, or you can simply add them up. (Using the credit card, you spent

a total of $13 on food.)

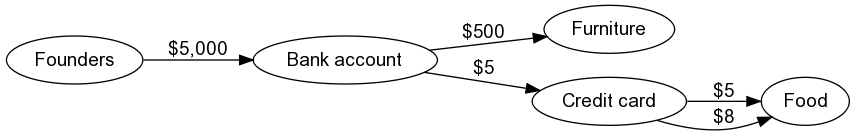

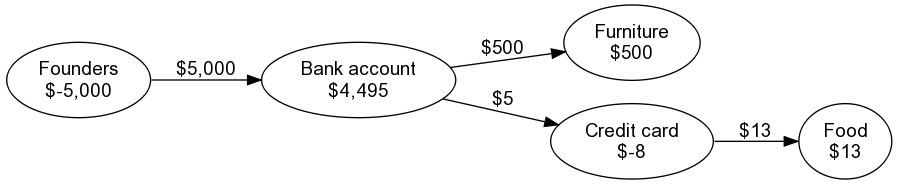

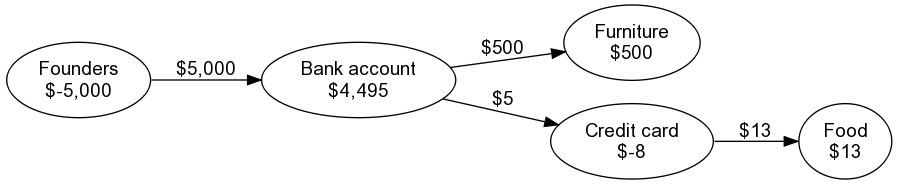

Accounts have balances

Every node in this graph is an account in accountant-speak (whether or not it is held by a bank),

and every account has a balance. The balance is a single number for each account, and it is

determined completely by the transactions in and out of the account:

- At the beginning of time, the value at each node is zero.

- At each node, for each incoming edge, add the edge’s label to the node’s value; for each

outgoing edge, subtract the edge’s label from the value.

After you’ve processed all the edges, the value at each node is that account’s balance. Our

graph now looks like this:

Note that the account balances have two nice properties:

- Because every transaction appears twice – once positive and once negative – the sum of

all account balances is always zero.

- If you partition the set of nodes into any two disjoint sets, and add up all of the balances

in each set, then the sum for the one set is always the negative sum of the other set

(because, after all, they have to add up to zero).

These properties are useful for sanity-checking your numbers; if they are violated,

“ur doin it wrong”. (This is what accountants mean when they talk about “balancing the books”.)

Doing business

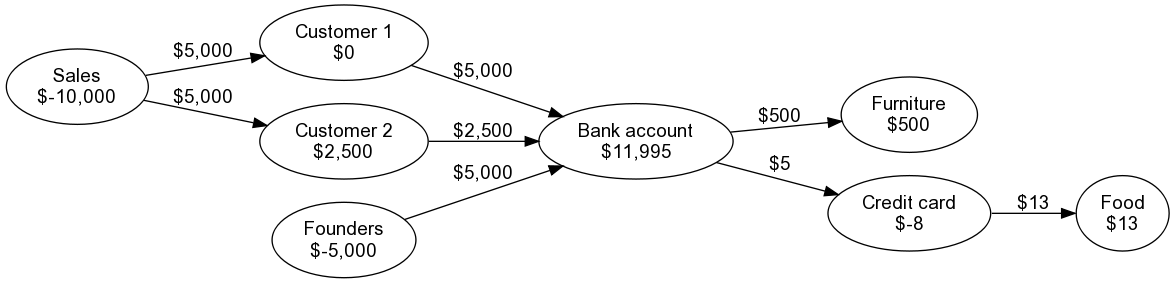

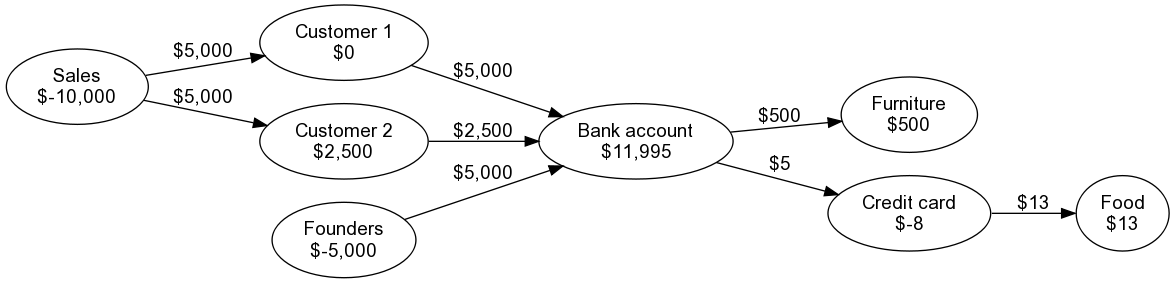

Strengthened by a bagel and a burrito, you go out and talk to some potential customers. And hey,

they love your product! It has a price tag of $5,000, and you sell it to two big enterprise

customers. One pays you right away (good stuff!); the other gives you $2,500 up front, but insists

that before they pay the rest, you need to implement that additional feature you foolishly

promised.

So you received $5,000 + $2,500 in cash from your customers, wired straight the company bank

account. Let’s add that to the graph:

But that’s not quite right. The price was $5,000 for each customer, and now it looks like you

charged two different prices. How do we represent our arrangement with customer 2?

The solution is to deconstruct the deal into two separate transactions: the sale (in which

the buyer agrees to buy, but no actual money changes hands) and the payment (when the cash

actually hits your bank account). We can draw it like this:

See what I’ve done here? I’ve just made up a new node, generically called it “sales”, and

added the actual $5,000 sales as a transaction from this “sales” account to the customer

accounts. Adding this extra node hasn’t changed your bank balance.

This makes sense when you think about the intuitive meaning of the balances.

The balance of each customer’s account is the amount they owe you: customer 1

has fully paid up (their incoming and outgoing transactions add up to the same), so their balance

is zero; customer 2 has contractually agreed to give you $5,000, but has so far only given you

half of that, so their balance is $2,500.

And the balance on the sales account is the value of stuff you’ve sold. Or rather, the negative

value. That looks a bit weird… but I’ll come back to that later. (BTW, if you wanted to

separately track sales for different customers or different products, no problem — just

add whatever nodes make sense for you. Just make sure that every transaction appears only

once as an edge, otherwise you’re making stuff up!)

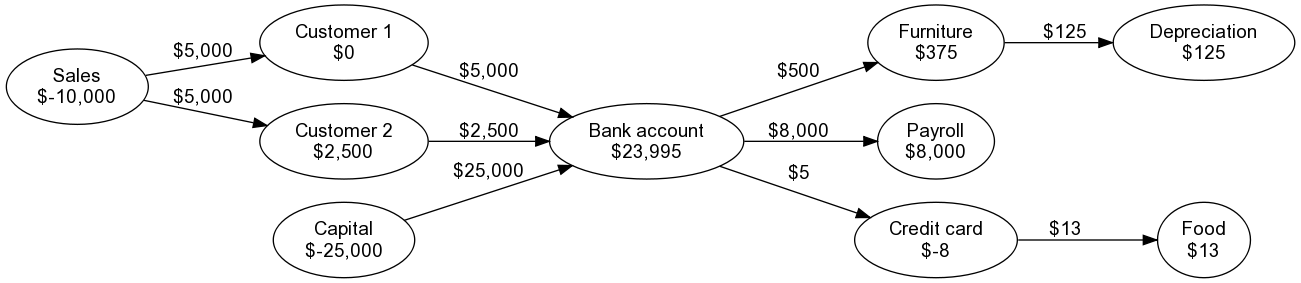

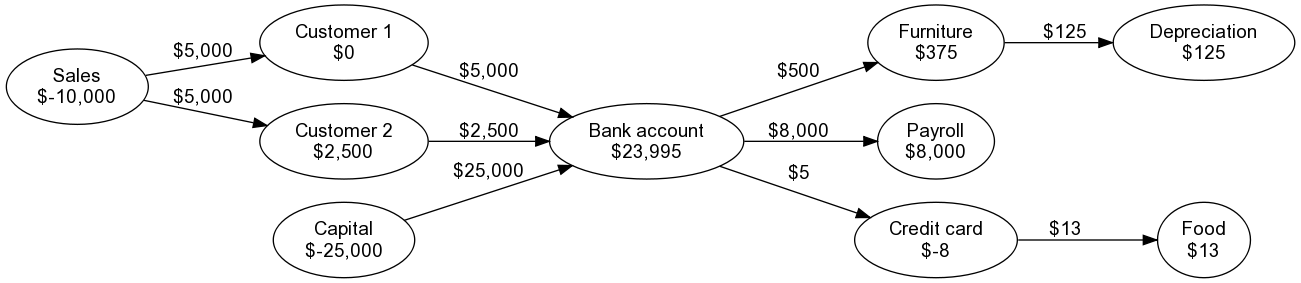

Finishing off the example

To round it off, let me add some more events to the story (= some more edges to the graph).

Not only have you made some sales, but now you also receive a $20,000 investment from

Y Combinator — congratulations! You and your co-founder can now afford to pay yourselves

a salary. You take $8,000 out of the company account.

Then you get set up with a company accountant, and they talk lots of jargon at you. For

some strange reason they are obsessed with correctly accounting for your office chair;

they want it to depreciate over four years, i.e. its value is gradually reduced to zero over

the course of that time. Fair enough, you say (even though you couldn’t care less what your

chair will be worth in four years’ time — surely by that time you’ll be the next Google

or Facebook, and you’ll have other things to worry about than chairs).

The resulting graph now looks like this:

Note how I have represented the transactions:

-

I have lumped together your founder investment with that of Y Combinator, under the

heading of “capital”. Put simply, this is money you got into the company by selling your

company’s shares, rather than by selling a product or service to a customer. As usual,

you can split founders and YC into separate accounts if you feel like it.

-

I’ve represented payroll (salaries) as just money straight out of the bank account. In

reality it’s a bit more complicated due to taxes, healthcare, benefits, etc. but the

principles stay the same. It’s just more nodes and edges in the graph.

-

I made depreciation for one year (one quarter of $500 = $125) go away from the

“furniture” account. Intuitively, this means that the balance of the “furniture” account

is the value that your furniture still has now. Each year, you add another $125 edge

from “furniture” to “depreciation”, until after four years, the balance of “furniture”

drops to zero (assuming you haven’t bought any more chairs in the meantime, in your quest

for world domination).

The profit and loss statement

At this point, if you’re getting weary, I don’t blame you. But the good news: we’ve finished

building our graph! Now I will show you how this graph representation maps to two standard

financial statements most commonly used in managing a company: the profit and loss statement

(“P&L”), and the balance sheet. This is useful, because as a startup founder you’ll sooner

or later have to discuss these documents with your investors/advisors, and so you might as

well learn what the hell they mean.

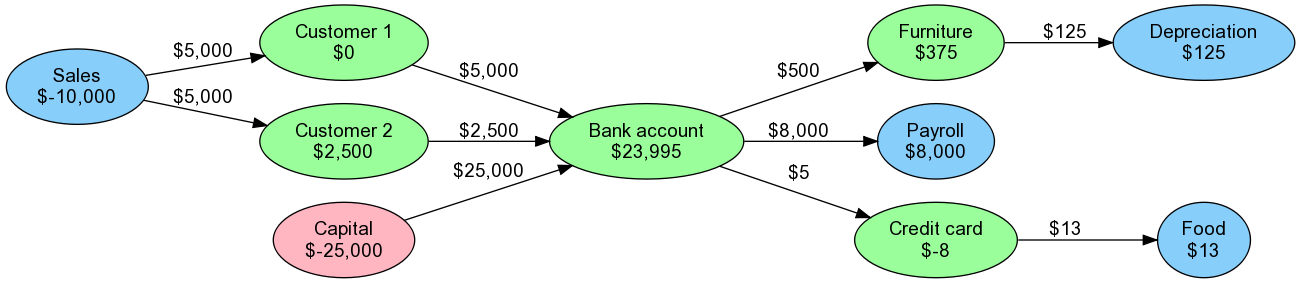

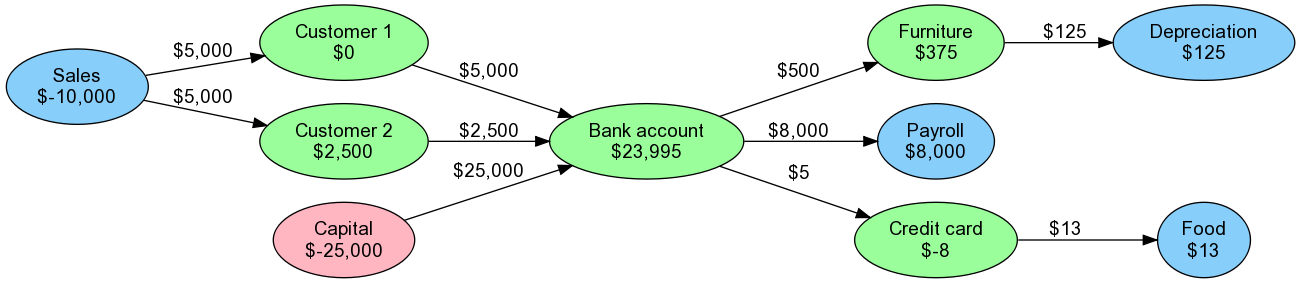

In order to produce these statements, I need to get out the crayons. Here is the same graph

as before, with the nodes coloured in:

Explaining the colours (putting the accounting terminology in brackets, since you’re likely to

encounter these words):

- Green for stuff that you have (“assets”), e.g. money in the bank, or things which you

bought and you could sell again, such as furniture. Also green for people/companies who

owe you money (“debtors”, such as Customer 2), and people/companies to whom you owe

money (“liabilities”/”creditors”, such as your upcoming credit card bill for that burrito).

- Blue for sales of your product/service (“revenue”) and money you spent that you’re not going

to get back (“expenses”/”overheads”). The office chair is green, because you could sell it

again if you wanted to, but the bagel is blue, because once you’ve bought (and eaten) the

bagel, that’s it – no going back.

- Pink for money from investors (or yourself) that you got by selling shares (“capital”).

(If you get a bank loan, that’s green, not pink, because you owe the bank to pay it back.)

Every one of your nodes should fall into exactly one of these categories. If not, something

has gone wrong, or you have discovered some bit of the accounting world that I don’t yet know

about.

With these colours set, the profit and loss statement is simply a list of all the blue nodes,

and the profit or loss of the company is the sum of all of the blue nodes’ balances. The way we’ve

calculated things, a negative value is a profit, and a positive value is a loss. That’s confusing,

so you typically flip the sign when reporting the number (so that a profit is positive).

Written in the standard way, our P&L looks like this:

| Revenue |

Sales |

$10,000 |

| Total revenue |

$10,000 |

|

| Expenses |

Payroll |

$8,000 |

| Depreciation |

$125 |

| Food |

$13 |

| Total expenses |

$8,138 |

|

| Total |

Profit/Loss |

$1,862 |

(= total revenue - total expenses) |

The meaning is fairly intuitive. You sold $10,000 worth of stuff, and spent only $8,138 in the

process, so you made $1,862 profit.

The profit and loss statement is calculated over a period of time (usually a month, a quarter or a

year), and it’s often interesting to compare two different periods. To calculate it for a period,

filter your transactions to only include those which occurred within that period, and add up the

account balances for just those transactions.

One thing to watch out for: profit doesn’t say anything about your bank account. The bank account

is a green node, but we’re only looking at blue nodes here. In this example, you ended up with

$23,995 in the bank, even though investors put in $25,000: you made a profit, yet still have less

money in the bank than you did before, because Customer 2 hasn’t yet fully paid. That’s why it’s

possible for a company to be profitable but still run out of money!

The Balance Sheet

The balance sheet is a bit less intuitive than the P&L, but it’s quite a powerful document. It

summarises what the company currently has and doesn’t have, and why.

Remember what I said earlier about partitioning the nodes into two disjoint sets, and their

summed balances adding to zero? That’s exactly what happens on the balance sheet. We take all of

the nodes in the graph; on the one side we consider all of the green nodes, and on the other side

all the blue and pink nodes. The sum of all of the blue and pink nodes’ balances is minus the sum

of all of the green nodes’ balances.

Now, by convention, accountants flip the sign on all of the blue and pink nodes’ balances, which

means that the two sums end up being equal. And that’s why it’s called a balance sheet.

In our example, it looks like this:

| Assets |

Bank account |

$23,995 |

| Debtors |

$2,500 |

| Furniture |

$375 |

| Total assets |

$26,870 |

|

| Liabilities |

Credit card |

$8 |

| Total liabilities |

$8 |

|

| Total assets less total liabilities |

$26,862 |

|

| Equity |

Profit/Loss |

$1,862 |

| Capital |

$25,000 |

| Total equity |

$26,862 |

The top block (assets and liabilities) corresponds to the green nodes in the graph, whilst

the bottom block contains the pink node (capital) and the sum of all of the blue nodes. We already

showed all of the detail for the blue nodes on the Profit and Loss statement above; on the balance

sheet we can sum them all up to a single number.

Some more sign-flipping has occurred here: I’ve written liabilities, equity and P&L with their

signs flipped (which usually, but not always, has the effect of making the numbers positive).

That doesn’t change anything fundamental about the graph structure, it just puts things into the

conventional schema.

So how can you interpret the balance sheet? There are various things you can read from it. You can

see how much money is in the bank, and how much of that money has already been promised to other

people (liabilities). You can see how much of the money in the bank came from investors, vs. how

much came from sales. And it shows how much money is due to come in soon, from sales that have

closed but haven’t yet been fully paid.

The total of the balance sheet is a lower bound on the value of your company. It’s a very

pessimistic figure — it assumes that your team, your technology, your brand etc. are all worth

precisely nothing; if your company raises money from investors, your valuation will be much higher

than the balance sheet figure, since that valuation includes the value of team, technology, brand

etc in the form of a wild guess. In established companies you can find “intangible assets” on the

balance sheet, but since they are very hard to value, I suspect it’s not worth bothering with

unless you know what you are doing.

That’s the end of our whirlwind tour through the world of accounting. If you’re a real accountant

reading this, please forgive my simplifications; if you spot any mistakes, please let me know.

For everyone else, I hope this has been useful. To find out when I write something new, please

follow me on Twitter.

If you found this post useful, please

support me on Patreon

so that I can write more like it!

To get notified when I write something new,

follow me on Bluesky or

Mastodon,

or enter your email address:

I won't give your address to anyone else, won't send you any spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.