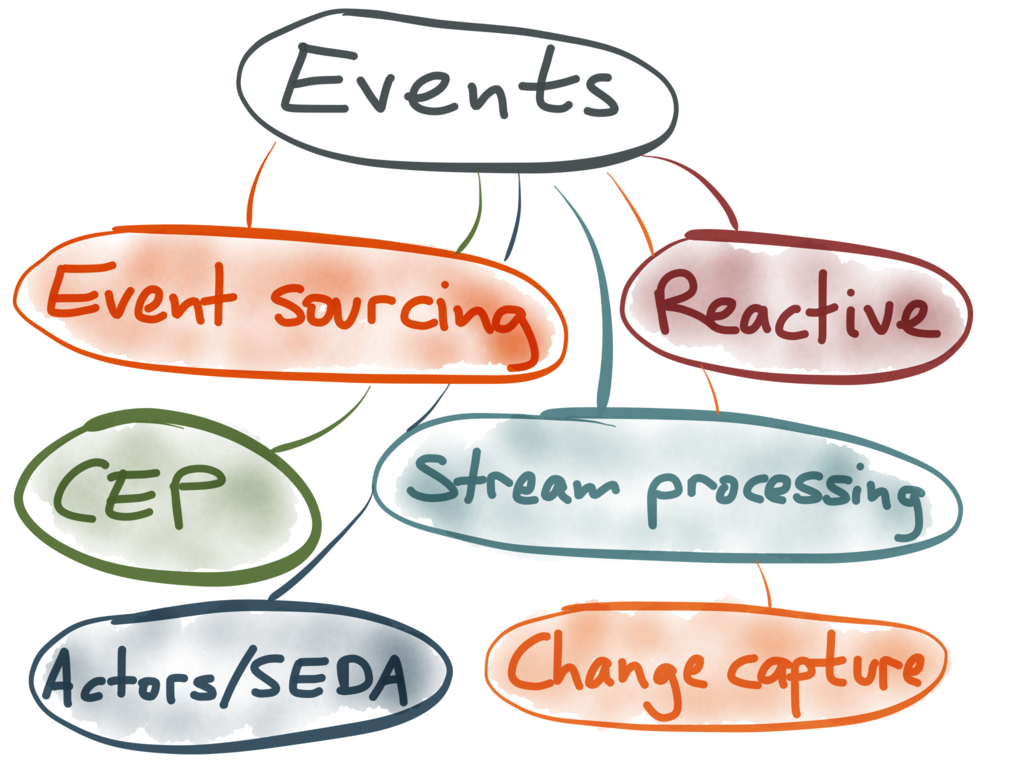

Stream processing, Event sourcing, Reactive, CEP… and making sense of it all

Published by Martin Kleppmann on 29 Jan 2015.

This is an edited transcript of a

talk I gave at

/dev/winter 2015. It was originally published

on the Confluent blog.

Some people call it stream processing. Others call it Event Sourcing or CQRS. Some even call it

Complex Event Processing. Sometimes, such self-important buzzwords are just smoke and mirrors,

invented by companies who want to sell you stuff. But sometimes, they contain a kernel of wisdom

which can really help us design better systems.

In this talk, we will go in search of the wisdom behind the buzzwords. We will discuss how event

streams can help make your application more scalable, more reliable and more maintainable. Founded

in the experience of building large-scale data systems at LinkedIn, and implemented in open source

projects like Apache Kafka and Apache Samza, stream processing is finally coming of age.

In this presentation, I’m going to discuss some of the ideas that people have about processing event

streams. The idea of structuring data as a stream of events is nothing new, but I’ve recently

noticed this idea reappearing in many different places, often with different terminology and

different use cases, but with the same underlying principles.

The problem when a technique becomes fashionable is that people start generating a lot of hype and

buzzwords around it, often reinventing ideas that are already commonplace in a different field, but

using different words to describe the same thing. In this talk I’m going to try to cut through some

of the hype and jargon in the general area of stream processing, and try to get down to the

underlying fundamental ideas.

Although the jargon can be off-putting when you first encounter it, there’s no need to be scared.

A lot of the ideas are quite simple when you get down to the core. Also, there are a lot of good

ideas which are worth learning about, because they can help us build applications better.

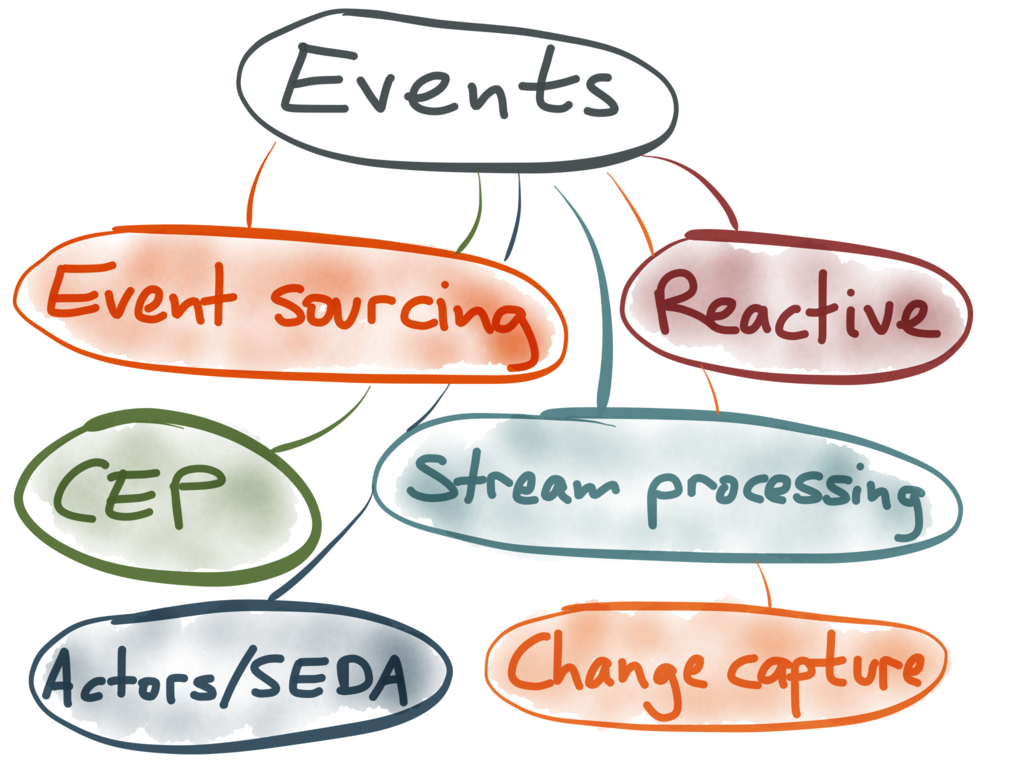

The notion of processing events appears in many different areas, which is really confusing at first.

People in different fields use different vocabulary to refer to the same thing. I think this is

mainly because the techniques originated in different communities of people, and people seem to

often stick within their own community and not look at what their neighbours are doing.

The current tools for distributed stream processing have come out of internet companies like

LinkedIn, with philosophical roots in database research of the early 2000s. On the other hand,

complex event processing (CEP) originated in

event simulation research in the 1990s and is now used

for operational purposes in enterprises. Event sourcing has its roots in the domain-driven design

community, which deals with enterprise software development — people who have to work with very

complex data models, but often smaller datasets than the internet companies.

My background is in internet companies, but I’m doing my best to understand the jargon of the other

communities, and figure out the commonalities and differences. If I’ve misunderstood something,

please correct me.

To make this concrete, I’m going to start by giving an example from the field of stream processing,

specifically analytics. I’ll then draw parallels with other areas.

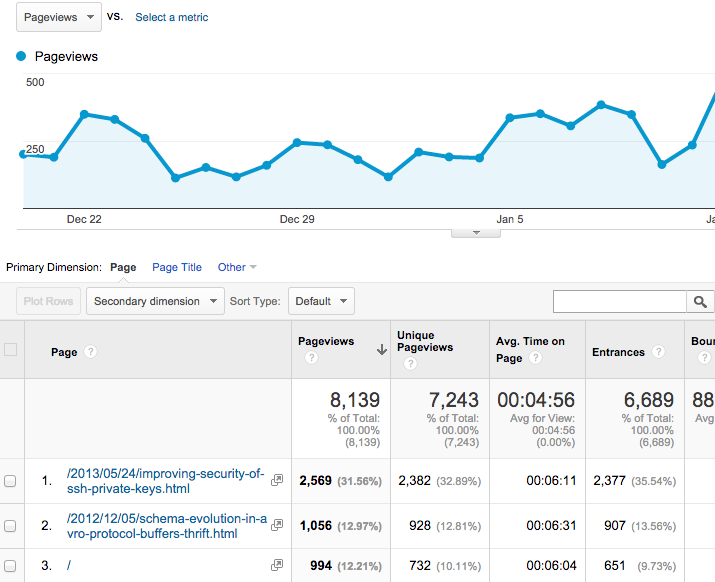

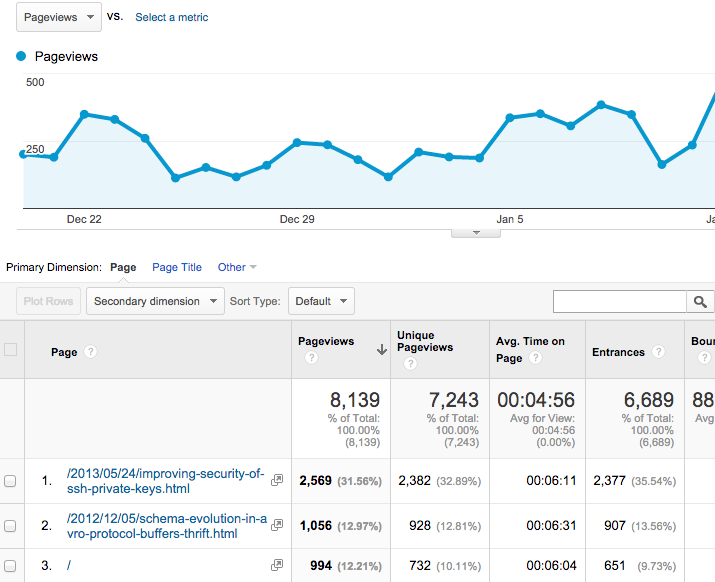

To start with, take something like Google Analytics. As you probably know, Google Analytics is a bit

of Javascript that you can put on your website, and that keeps track of which pages have been viewed

by which visitors. An administrator can then explore this data, breaking it down by time period, or

by URL, and so on.

How would you implement something like Google Analytics?

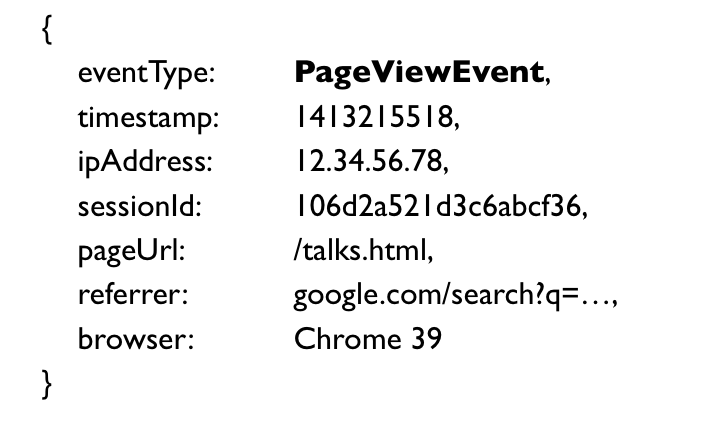

First take the input to the system. Every time a user views a page, we need to log an event to

record that fact. A page view event may look something like this (using a kind of pseudo-JSON):

A page view has an event type (PageViewEvent), a Unix timestamp that indicates when the event

happened, the IP address of the client, the session ID (this may be a unique identifier from

a cookie, which allows you to figure out what series of page views is from the same person), the URL

of the page that was viewed, how the user got to that page (for example, from a search engine, or

clicking a link from another site), the user’s browser and language settings, and so on.

Note that each page view event is a simple, immutable fact. It simply records that something

happened.

Now, how do you go from these page view events to the nice graphical dashboard on which you can

explore how people are using your website?

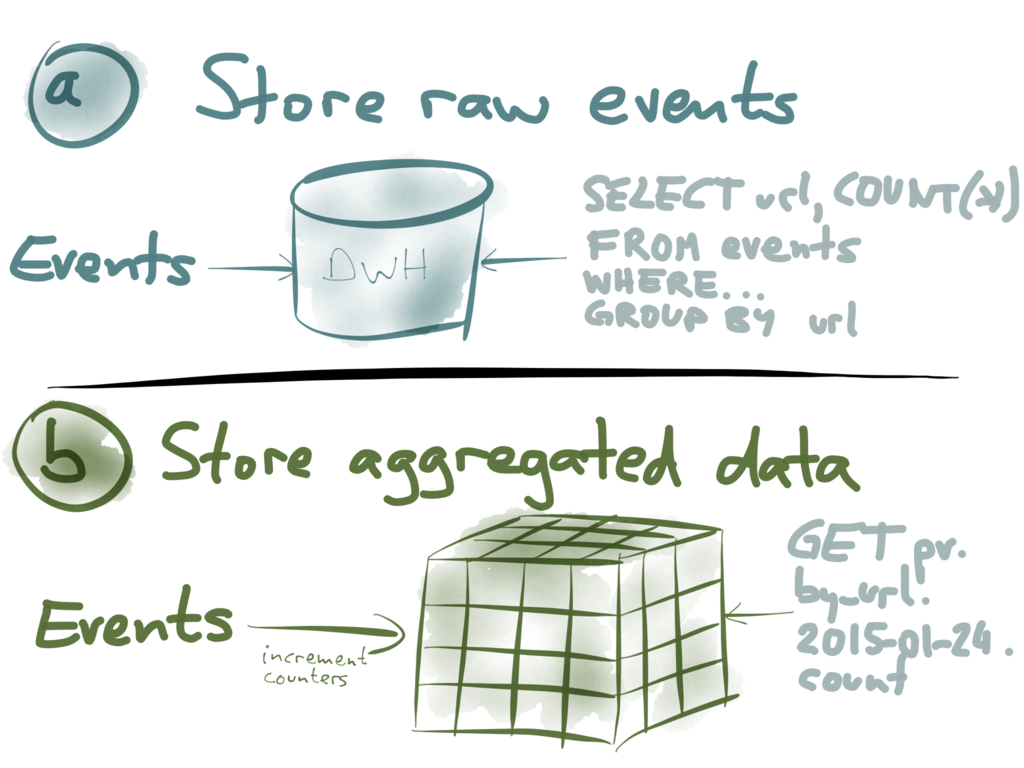

Broadly speaking, you have two options.

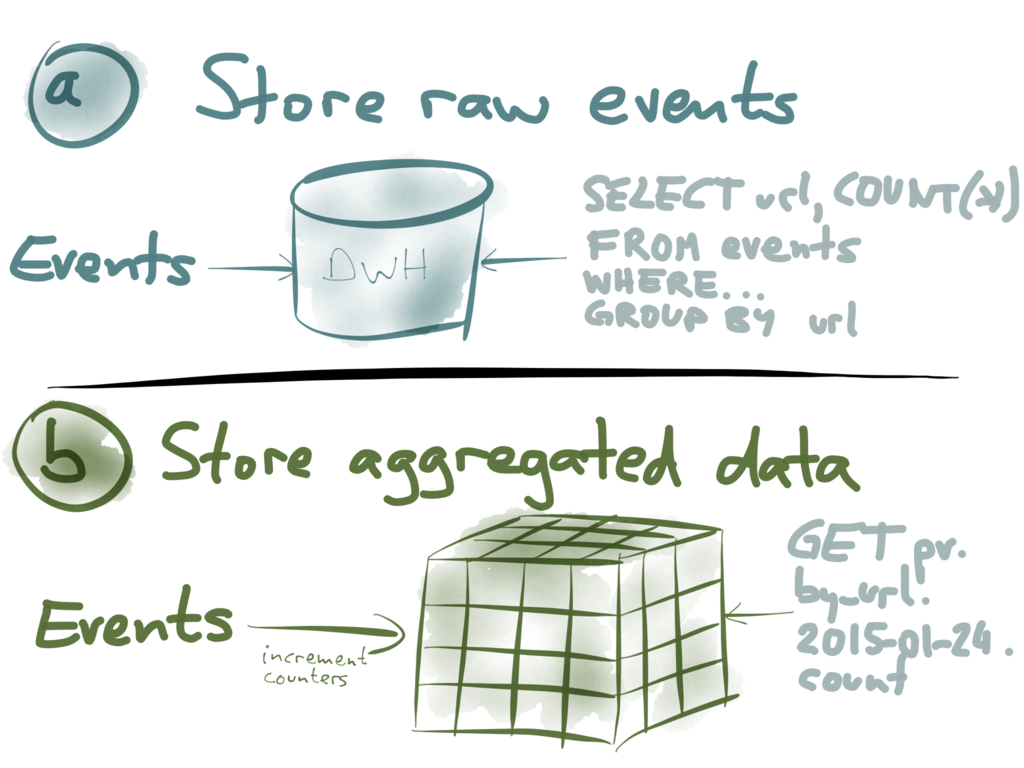

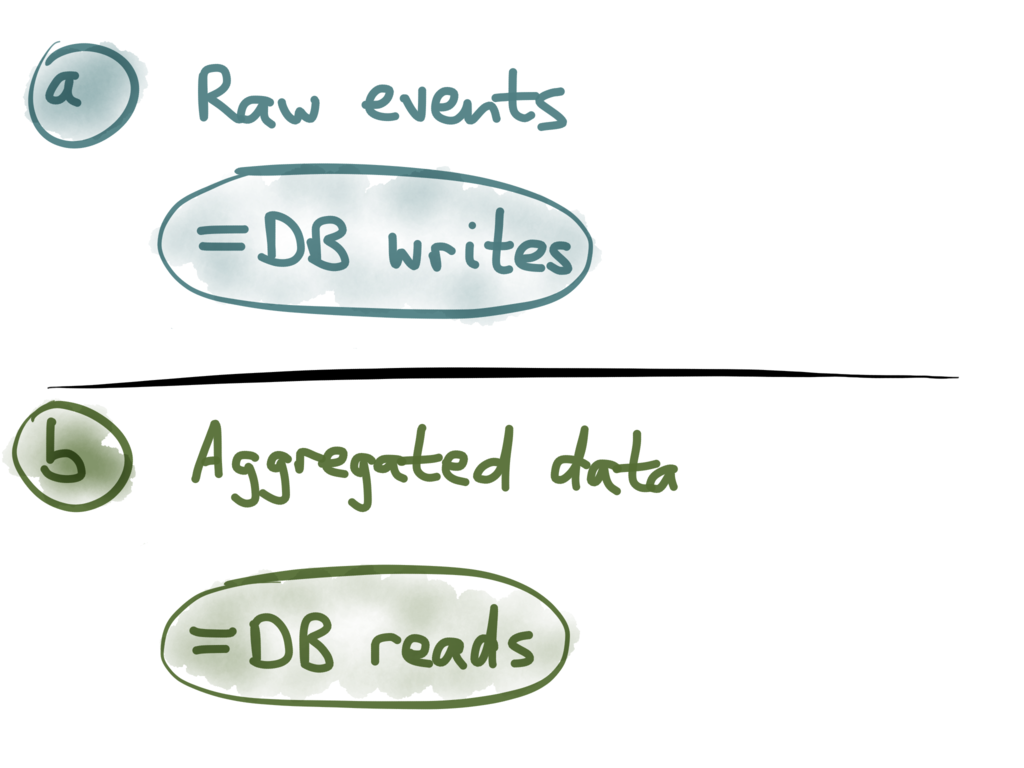

Option (a): you can simply store every single event as it comes in, dump them all in a big

database, a data warehouse or a Hadoop cluster. Now, whenever you want to analyze this data in some

way, you run a big SELECT query against this dataset. For example, you might group by URL and by

time period, you might filter by some condition, and then COUNT(*) to get the number of page views

for each URL over time. This will scan over essentially all the events, or at least some large

subset, and do the aggregation on the fly.

Option (b): if storing every single event is too much for you, you can instead store an

aggregated summary of the events. For example, if you’re counting things, you increment a few

counters every time an event comes in, and then you throw away the actual event. You might keep

several counters in something that’s called an OLAP cube:

imagine a multi-dimensional cube, where one dimension is the URL, another dimension is the time of

the event, another dimension is the browser, and so on. For each event, you just need to increment

the counters for that particular URL, that particular time, etc.

With an OLAP cube, when you want to find the number of page views for a particular URL on

a particular day, you just need to read the counter for that combination of URL and date. You don’t

have to scan over a long list of events; it’s just a matter of reading a single value.

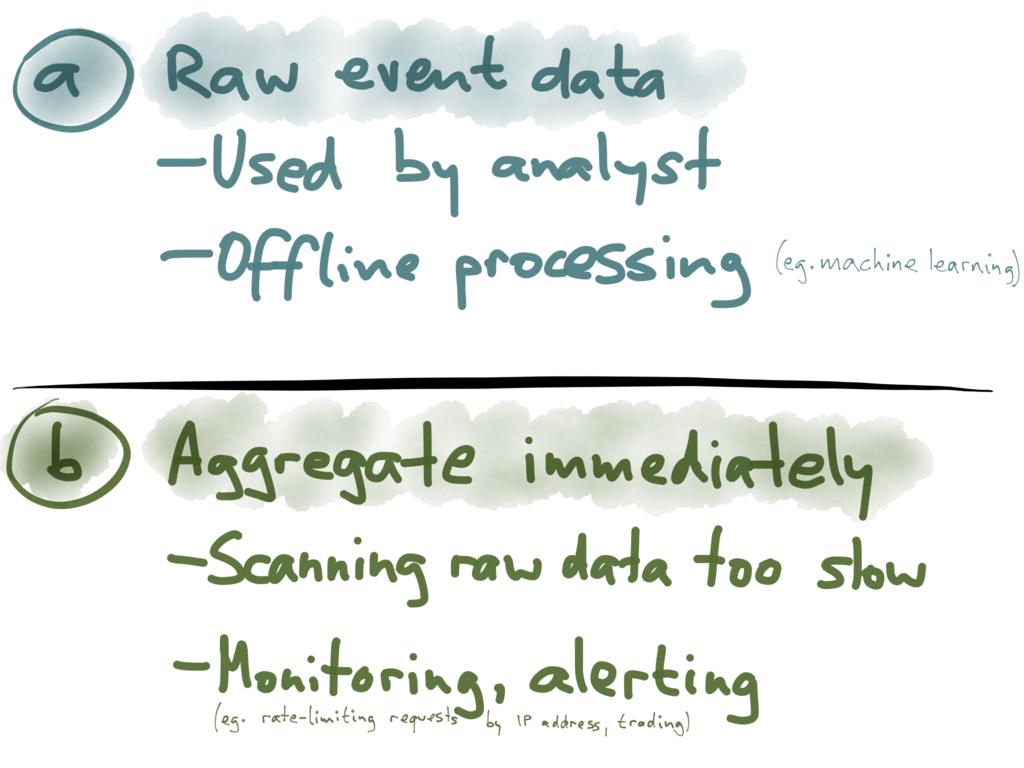

Now option (a) may sound a bit crazy, but it actually works surprisingly well. I believe Google

Analytics actually does store the raw events, or at least a large sample of events, and performs

a big scan over those events when you look at the data. Modern analytic databases have become really

good at scanning quickly over large amounts of data.

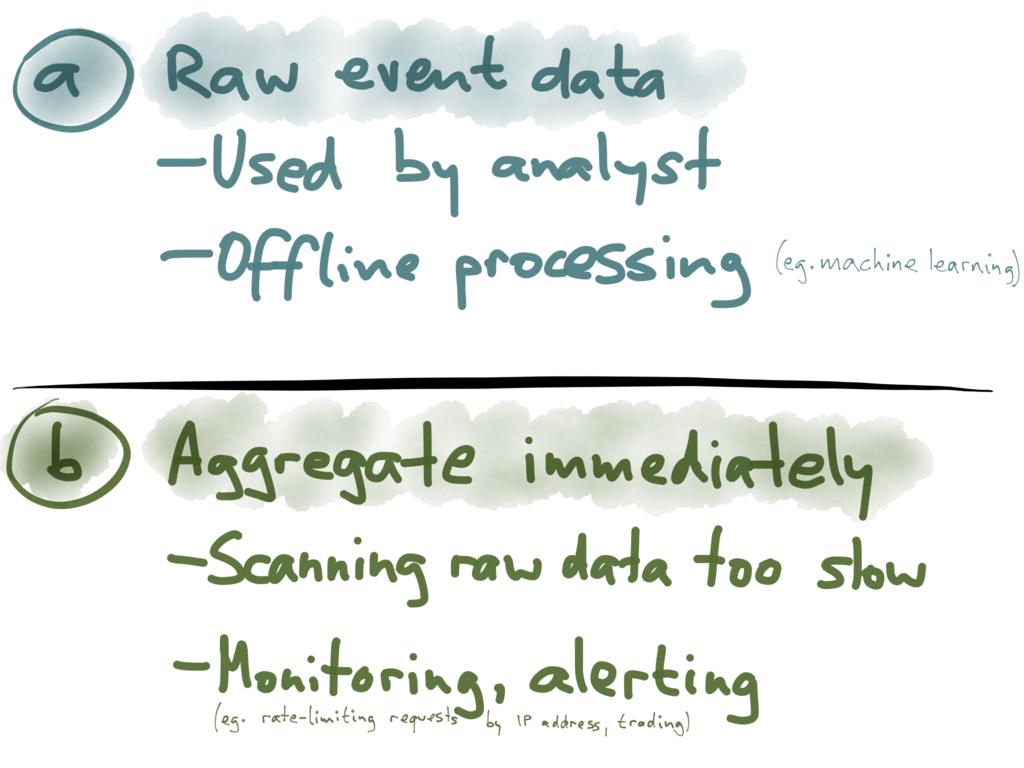

The big advantage of storing raw event data is that you have maximum flexibility for analysis. For

example, you can trace the sequence of pages that one person visited over the course of their

session. You can’t do that if you’ve squashed all the events into counters. That sort of analysis is

really important for some offline processing tasks, such as training a recommender system (“people

who bought X also bought Y”, that sort of thing). For such use cases, it’s best to simply keep all

the raw events, so that you can later feed them all into your shiny new machine learning system.

However, option (b) also has its uses, especially when you need to make decisions or react to things

in real time. For example, if you want to prevent people from scraping your website, you can

introduce a rate limit, so that you only allow 100 requests per hour from any particular IP address;

if a client goes over the limit, you block it. Implementing that with raw event storage would be

incredibly inefficient, because you’d be continually re-scanning your history of events to determine

whether someone has gone over the limit. It’s much more efficient to just keep a counter of number

of page views per IP address per time window, and then you can check on every request whether that

number has crossed your threshold.

Similarly, for alerting purposes, you need to respond quickly to what the events are telling you.

For stock market trading, you also need to be quick.

The bottom line here is that raw event storage and aggregated summaries of events are both very

useful. They just have different use cases.

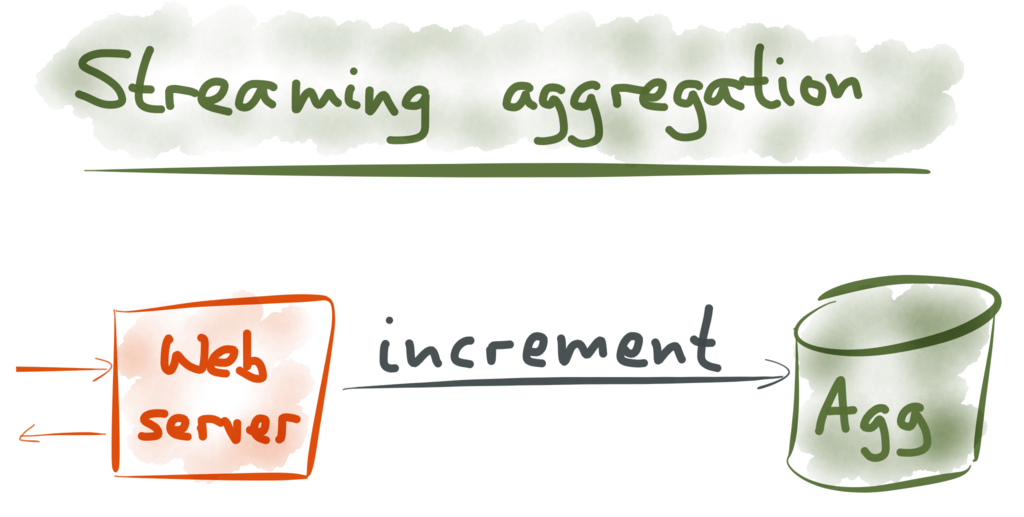

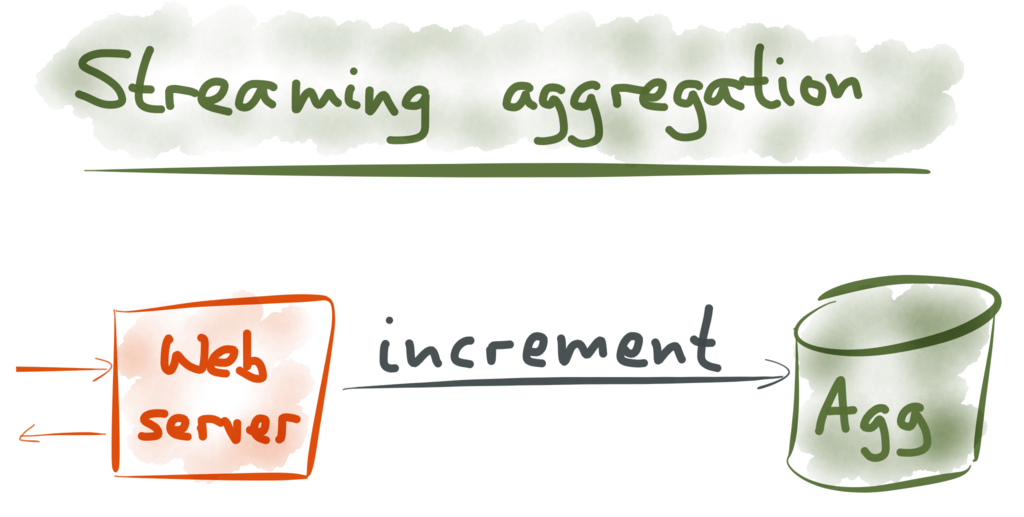

Let’s focus on those aggregated summaries for now. How do you implement those?

Well, in the simplest case, you simply have the web server update the aggregates directly. Say you

want to count page views per IP address per hour, for rate limiting purposes. You can keep those

counters in something like memcached or Redis, which have an atomic increment operation. Every time

a web server processes a request, it directly sends an increment command to the store, with a key

that is constructed from the client IP address and the current time (truncated to the nearest hour).

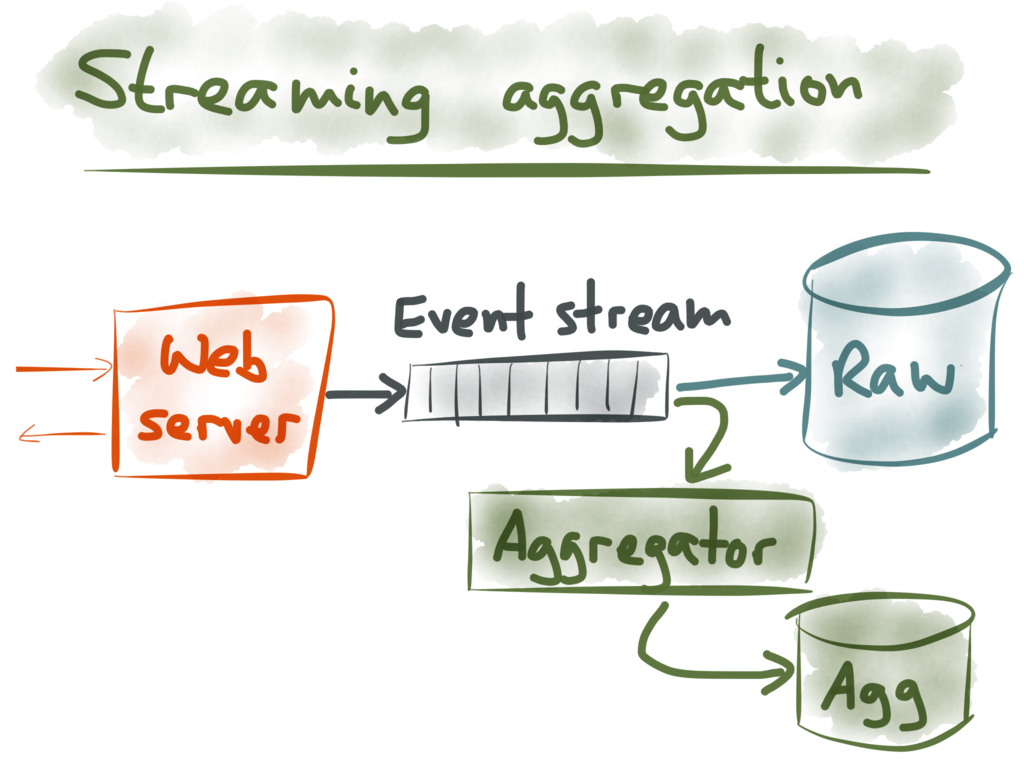

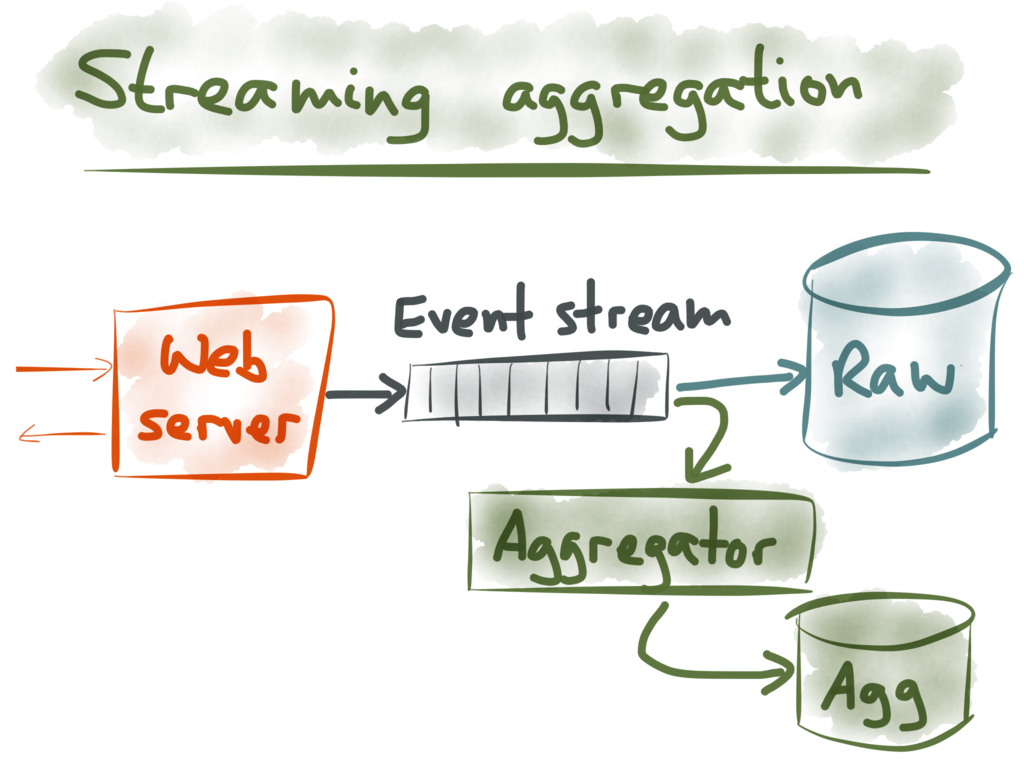

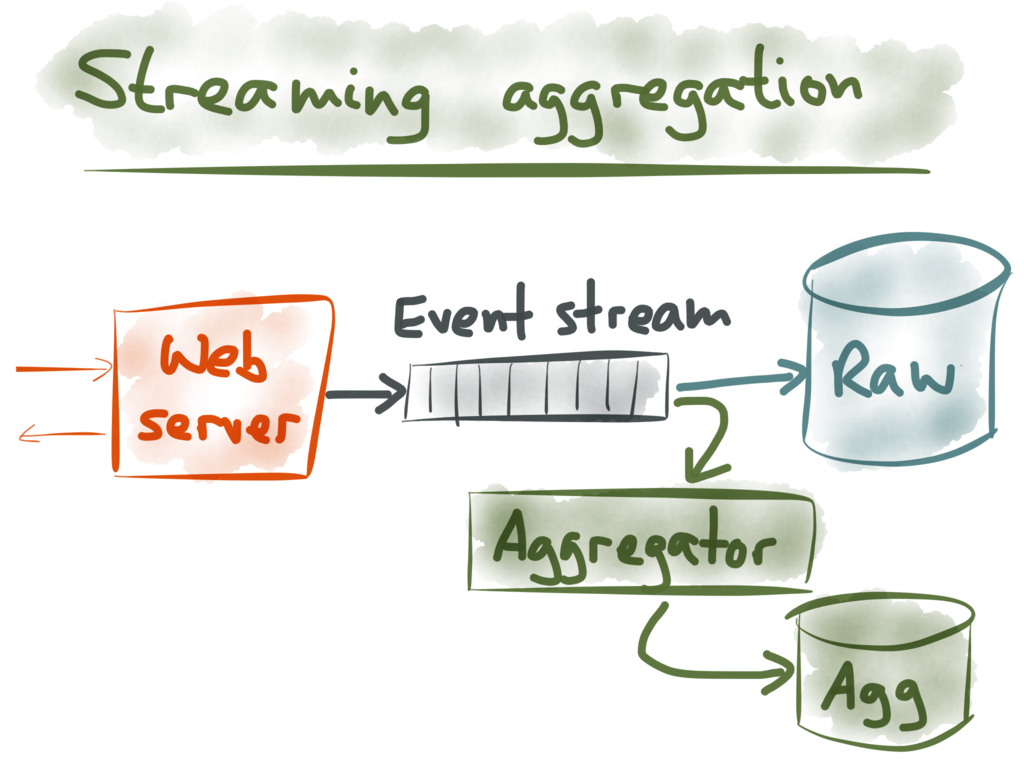

If you want to get a bit more sophisticated, you can introduce an event stream, or a message queue,

or an event log, or whatever you want to call it. The messages on that stream are the PageViewEvent

records that we saw earlier: one message contains the properties of one particular page view.

The nice thing about this architecture is that you can now have multiple consumers for the same

event data. You can have one consumer which simply archives the raw events to some big storage; even

if you don’t yet have the capability to process the raw events, you might as well store them, since

storage is cheap and you can use them in future. Then you can have another consumer which does some

aggregation (for example, incrementing counters), and another consumer which does something else.

Those can all feed off the same event stream.

Let’s now change topic for a moment, and look at similar ideas from a different field. Event

sourcing is an idea that has come out of the domain-driven design community — it seems to be fairly

well known amongst enterprise software developers, but it’s totally unknown in internet companies.

It comes with a large amount of jargon that I find very confusing, but there seem to be some very

good ideas in event sourcing.

So I’m going to try to extract those good ideas without going into all the jargon, and we’ll see

that there are some surprising parallels with my last example from the field of stream processing

analytics.

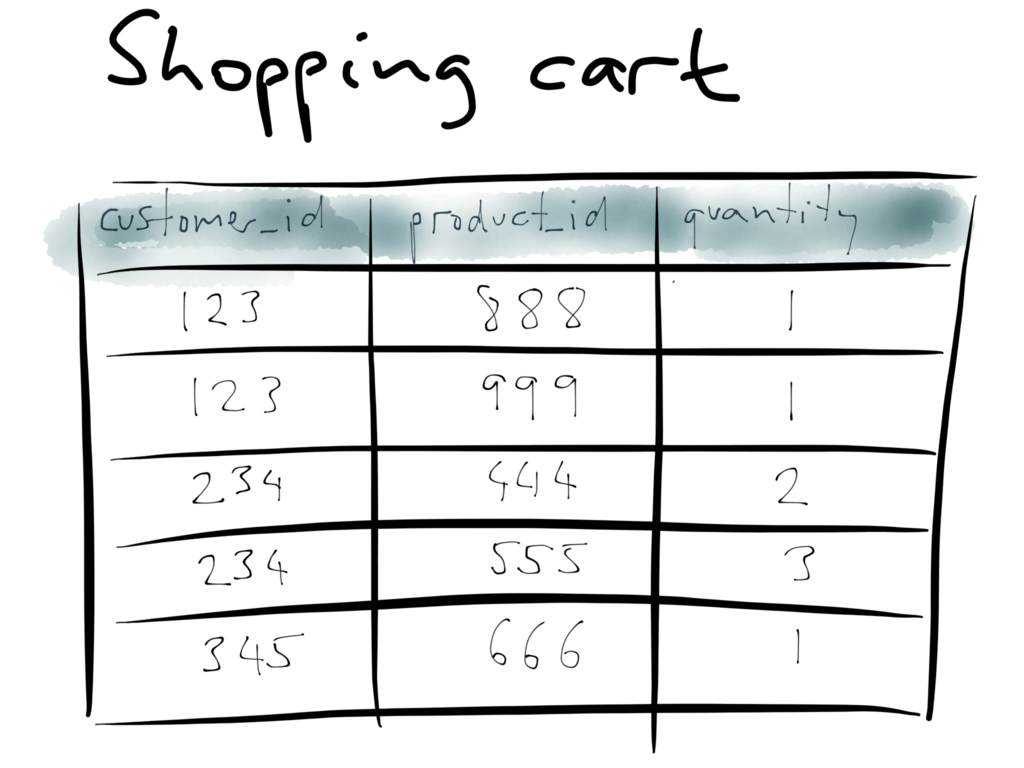

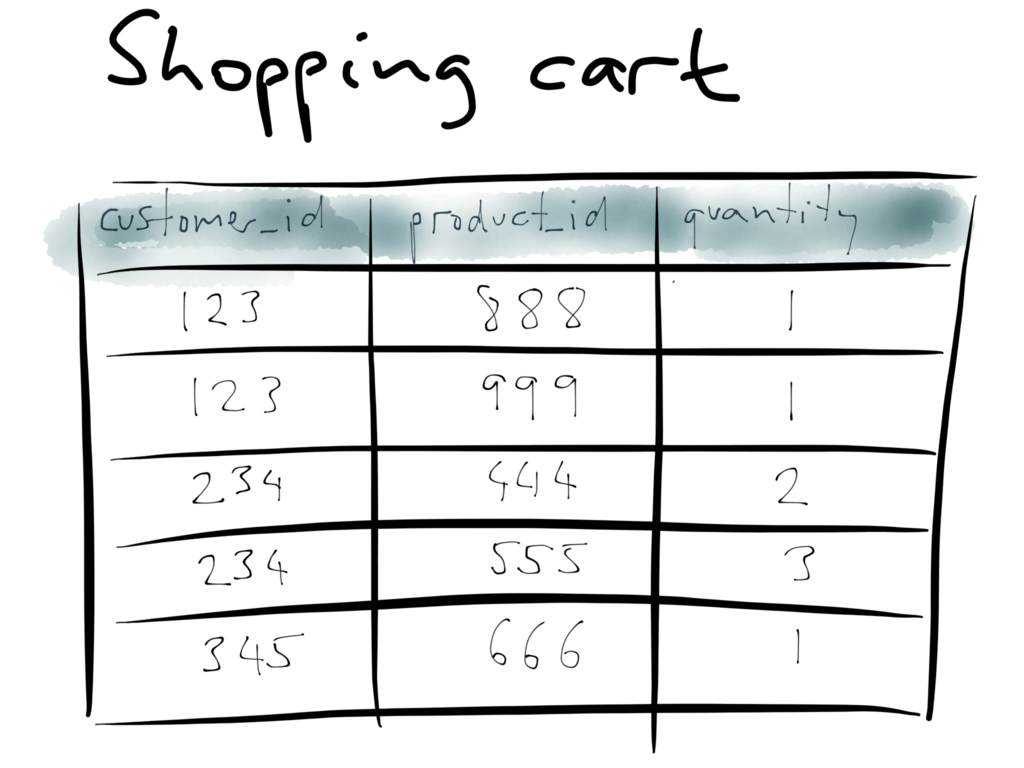

Event sourcing is concerned with how we structure data in databases. As example database I’m going

to use a shopping cart from an e-commerce website. Each customer may have some number of different

products in their cart at one time, and for each item in the cart there is a quantity. Nothing very

complicated here.

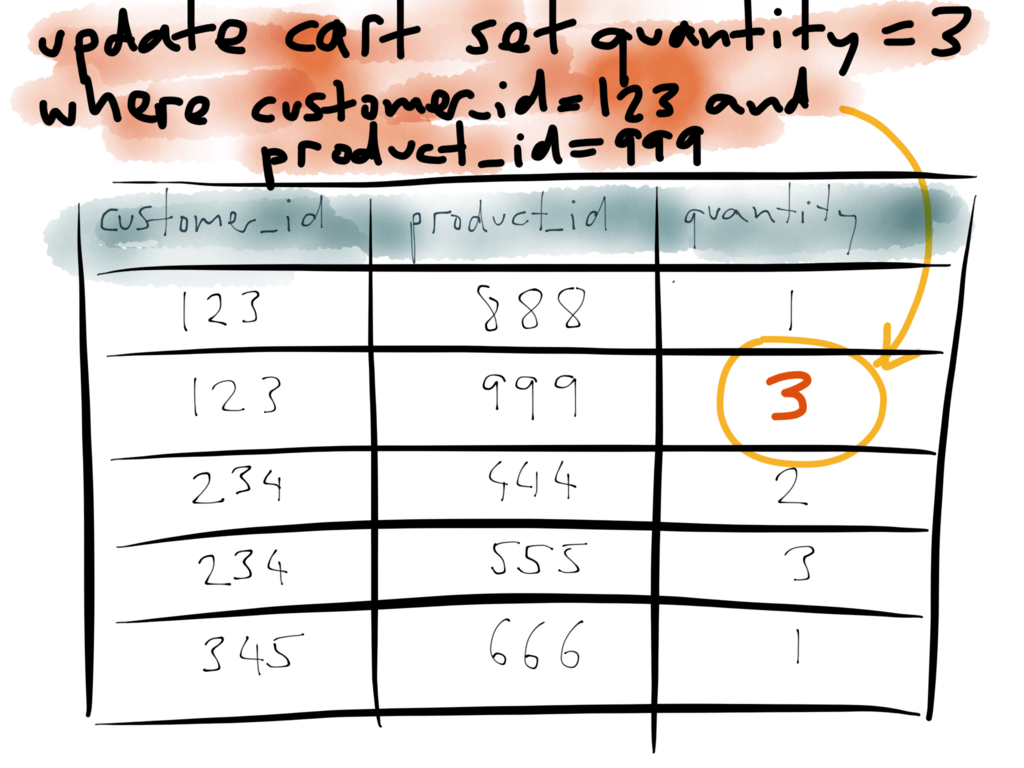

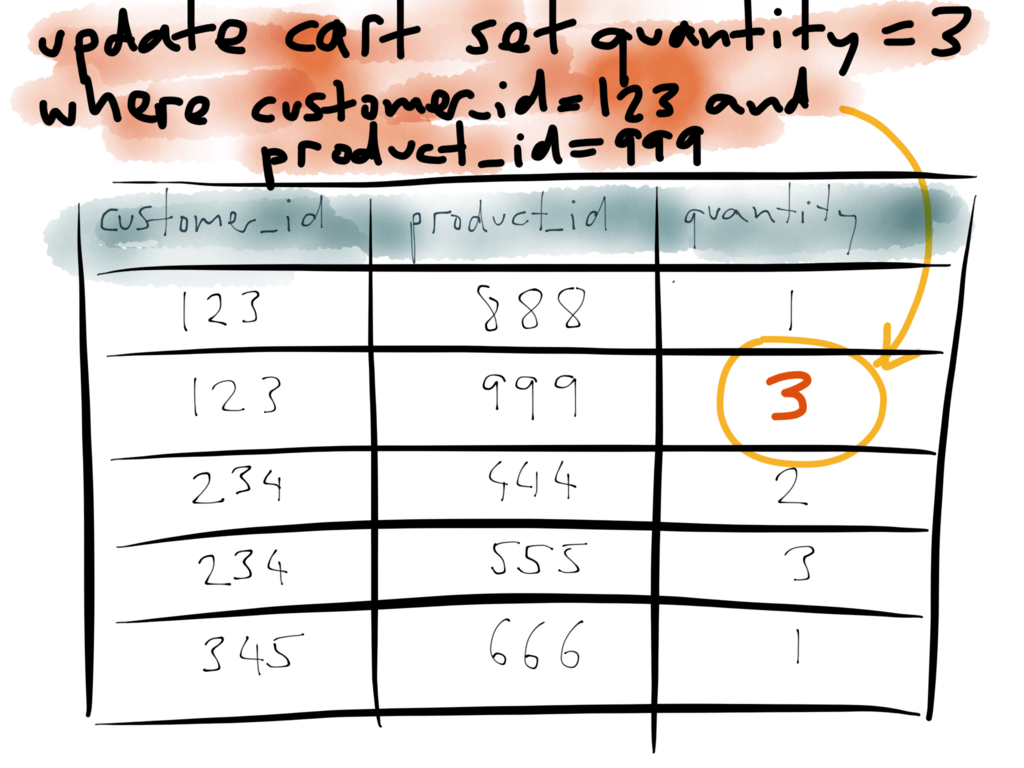

Now say that customer 123 updates their cart: instead of quantity 1 of product 999, they now want

quantity 3 of that product. You can imagine this being recorded in the database using an UPDATE

query, which matches the row for customer 123 and product 999, and modifies that row, changing the

quantity from 1 to 3.

This example uses a relational data model, but that doesn’t really matter. With most non-relational

databases you’d do more or less the same thing: overwrite the old value with the new value when it

changes.

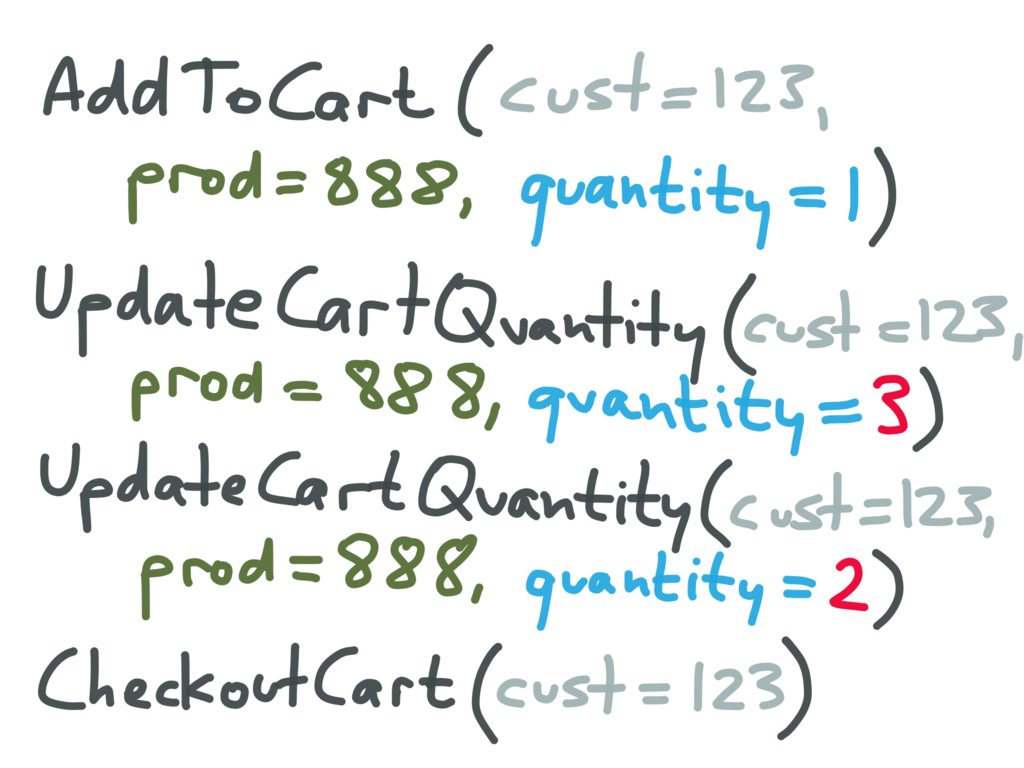

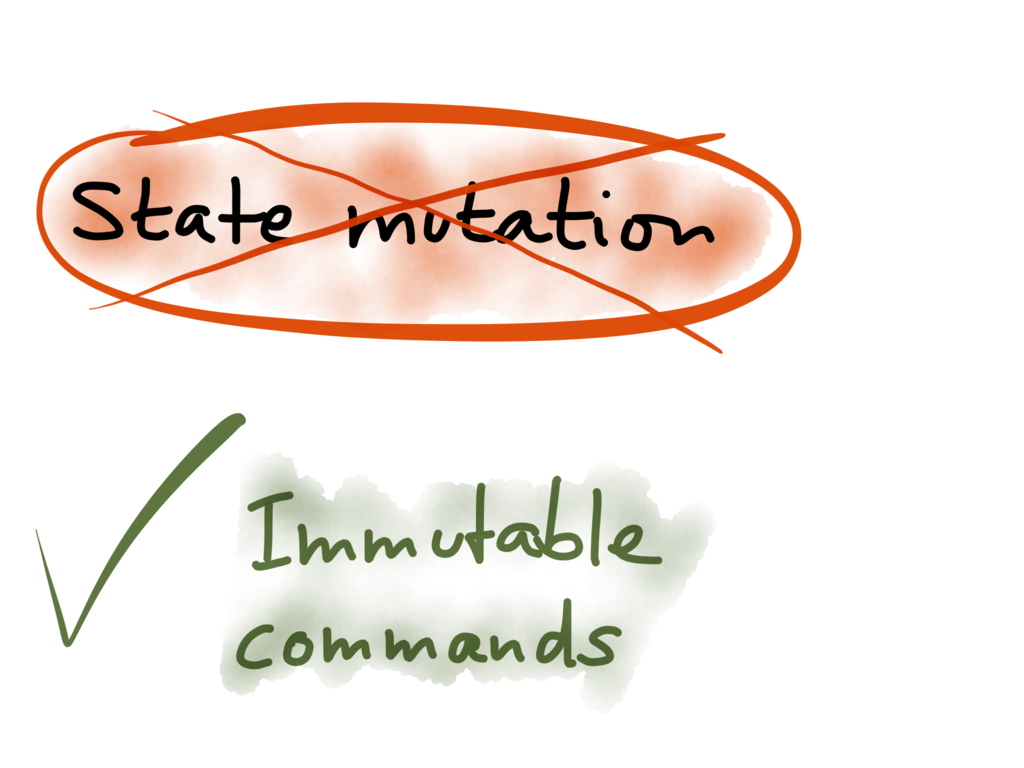

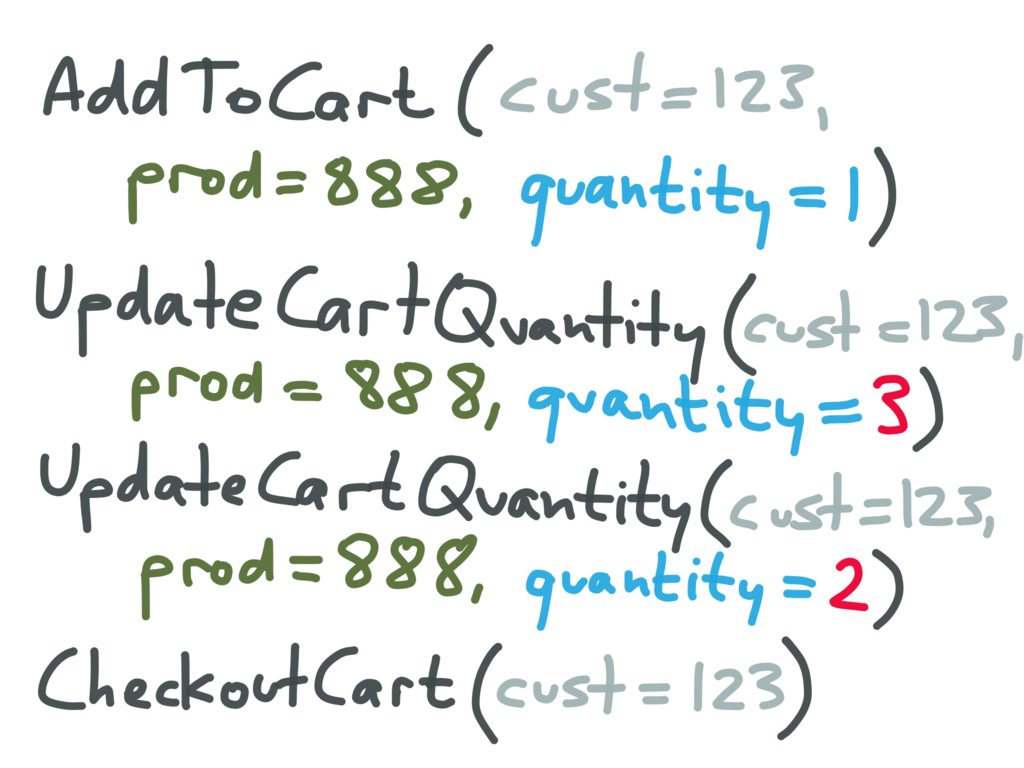

However, event sourcing says that this isn’t a good way to design databases. Instead, we should

individually record every change that happens to the database.

For example, we first record an AddToCart event when customer 123 first adds product 888 to their

cart, with quantity 1. We then record a separate UpdateCartQuantity event when they change the

quantity to 3. Later, the customer changes their mind again, and reduces the quantity to 2, and

finally they go to the checkout. Each of these actions is recorded as a separate event, and appended

to the database. You can imagine having a timestamp on every event too.

When you structure the data like this, every change to the shopping cart is an immutable event —

a fact. Even if the customer did change the quantity to 2, it is still true that at a previous point

in time, the selected quantity was 3. If you overwrite data in your database, you lose this historic

information. Keeping the list of all changes as a log of immutable events thus gives you strictly

richer information than if you overwrite things in the database.

And this is really the essence of event sourcing: rather than performing destructive state mutation

on a database when writing to it, we should record every write as a “command”, as an immutable

event.

And that brings us back to our stream processing example (Google Analytics). Remember we discussed

two options for storing data: (a) raw events, or (b) aggregated summaries.

What we have here with event sourcing is looking very similar. You can think of those event-sourced

commands (AddToCart, UpdateCartQuantity) as raw events: they comprise the history of what happened

over time. But when you’re looking at the contents of your shopping cart, you see the its current

state — the end result, which is what you get when you have applied the entire history of events and

squashed them together into one thing.

So the current state of the cart may say quantity 2. The history of raw events will tell you that at

some previous point in time the quantity was 3, but that the customer later changed their mind and

updated it to 2. The aggregated end result only tells you that the current quantity is 2.

Thinking about it further, you can observe that the raw events are the form in which it’s ideal to

write the data: all the information in the database write is contained in a single blob. You don’t

need to go and update five different tables if you’re storing raw events — you only need to append

the event to the end of a log. That’s the simplest and fastest possible way of writing to

a database.

On the other hand, the aggregated data is the form in which it’s ideal to read data from the

database. If a customer is looking at the contents of their shopping cart, they are not interested

in the entire history of modifications that led to the current state — they only want to know what’s

in the cart right now. So when you’re reading, you can get the best performance if the history of

changes has already been squashed together into a single object representing the current state.

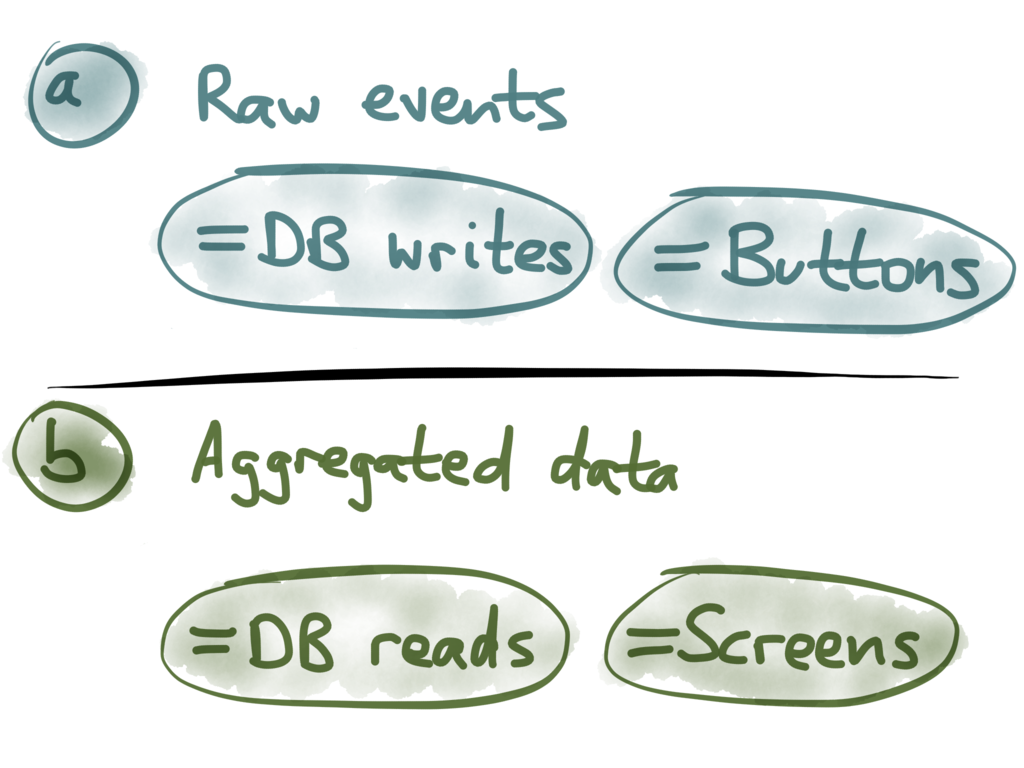

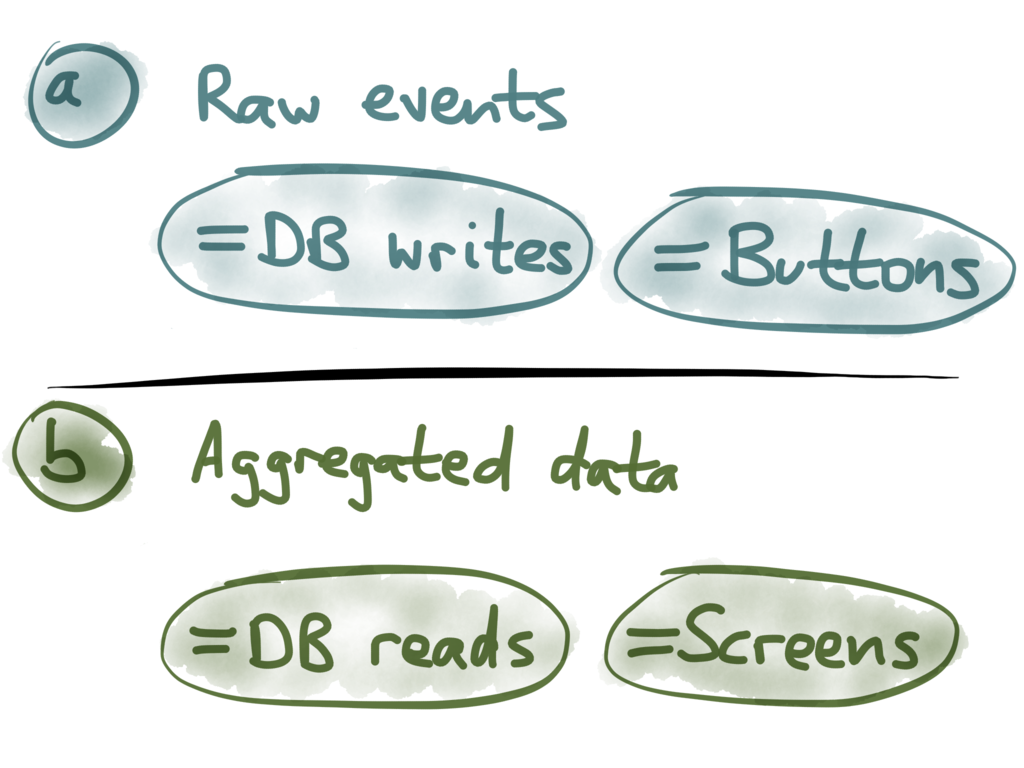

Going even further, think about the user interfaces that lead to database writes and database reads.

A database write typically happened because the user clicked some button: for example, they edited

some data, and now they click the save button. So, buttons in the user interface correspond to raw

events in the event sourcing history.

On the other hand, a database read typically happens because the user views some screen: they click

on some link or open some document, and now they need to read the contents. These reads typically

want to know the current state of the database. So screens in the user interface correspond to

aggregated state.

This is quite an abstract idea, so let me go through a few examples.

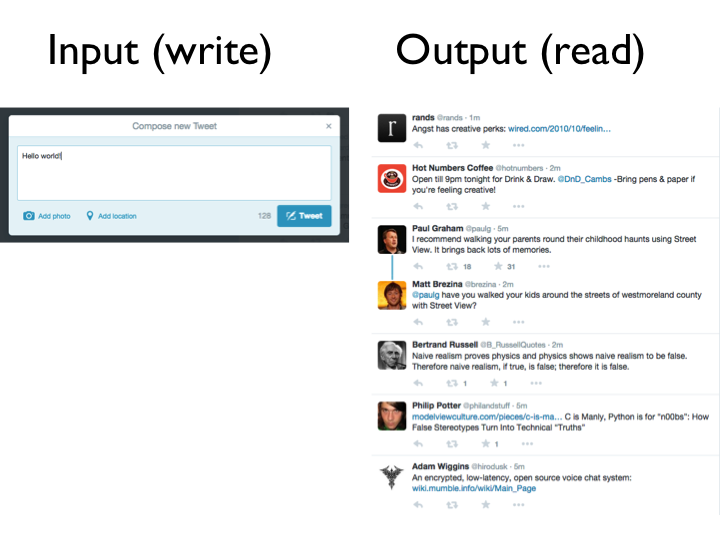

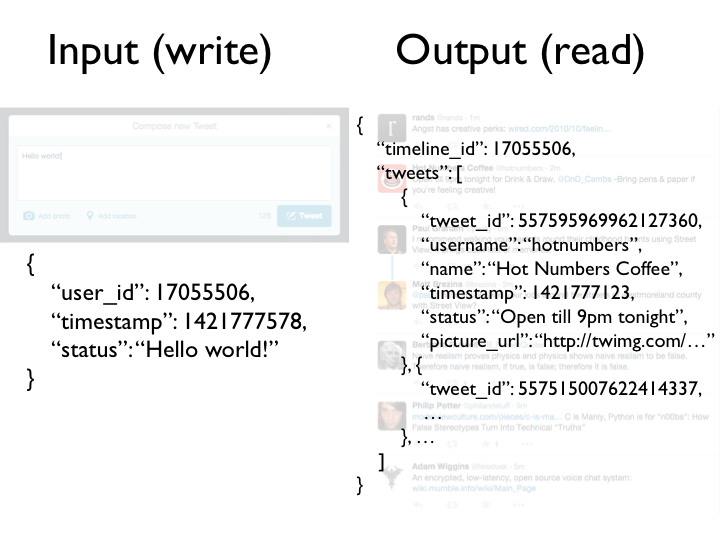

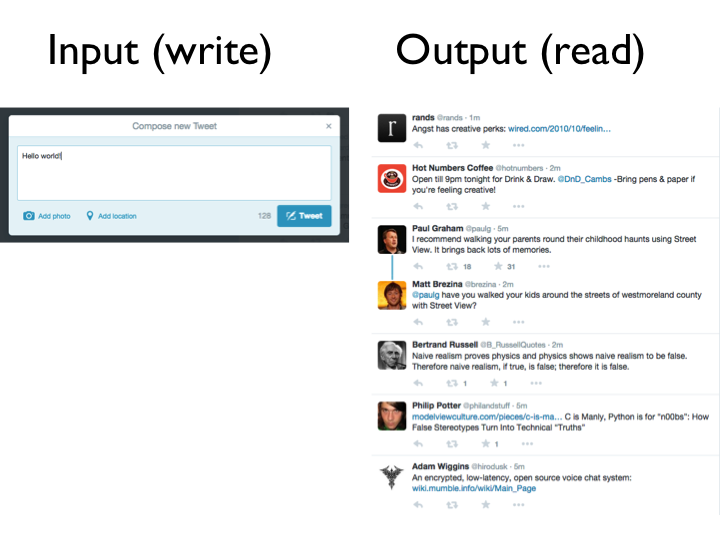

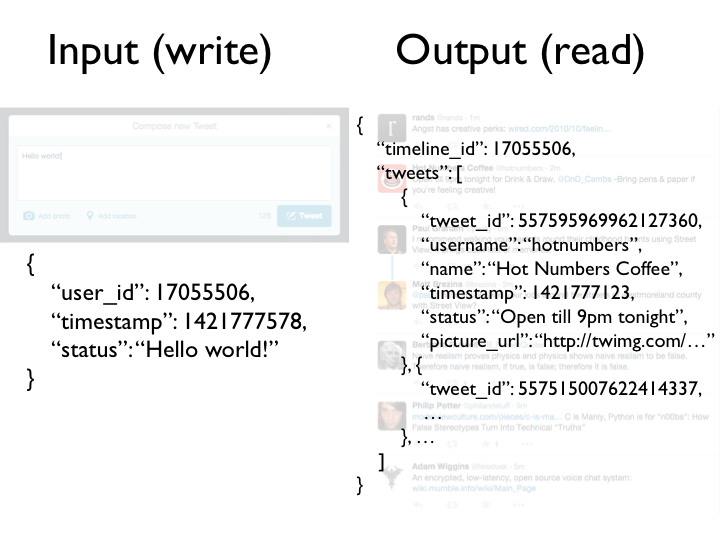

Take Twitter, for example. The most common way of writing to Twitter’s database — i.e. to provide

input into the Twitter system — is to tweet something. A tweet is very simple: it consists of some

text, a timestamp, and the ID of the user who tweeted. (Perhaps optionally a location, or a photo,

or something.) The user then clicks that “Tweet” button, which causes a database write to happen,

i.e. an event is generated.

On the output side, the way how you read from Twitter’s database is by viewing your timeline. It

shows all the stuff that was written by people you follow. It’s a vastly more complicated structure:

For each tweet, you now have not just the text, timestamp and user ID, but also the name of the

user, their profile photo, and other information that has been joined with the tweet. Also, the list

of tweets has been selected based on the people you follow, which may itself change.

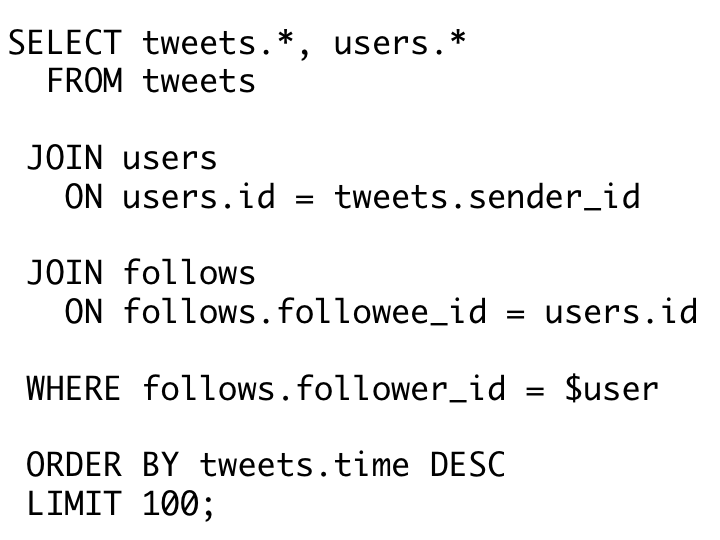

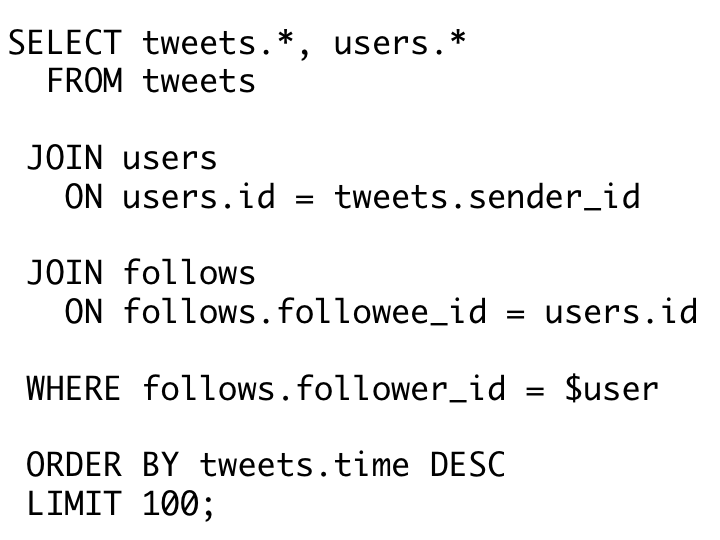

How would you go from the simple input to the more complex output? Well, you could try expressing it

in SQL, something like this:

That is, find all of the users who $user is following, find all the tweets that they have written,

order them by time and pick the 100 most recent. Turns out this query really doesn’t scale very

well. Do you remember in the early days of Twitter, when they kept having the fail whale all the

time? Apparently that was

essentially because they were using something like the query above.

When a user views their timeline, it’s too expensive to iterate over all the people they are

following to get those users’ tweets. Instead, Twitter must compute a user’s timeline ahead of time,

and cache it, so that it’s fast when a user looks at it. To do that, they need a process that

translates from the write-optimized event (a single tweet) to the read-optimized aggregate (a

timeline). Twitter has such a process, and calls it the

fanout service.

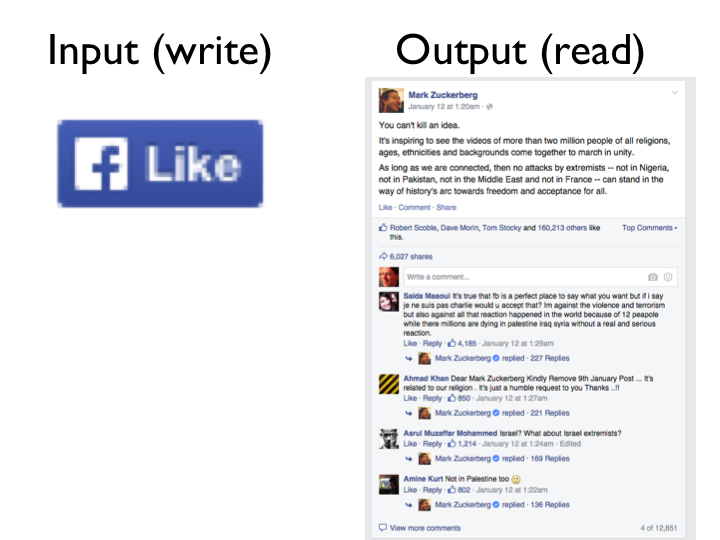

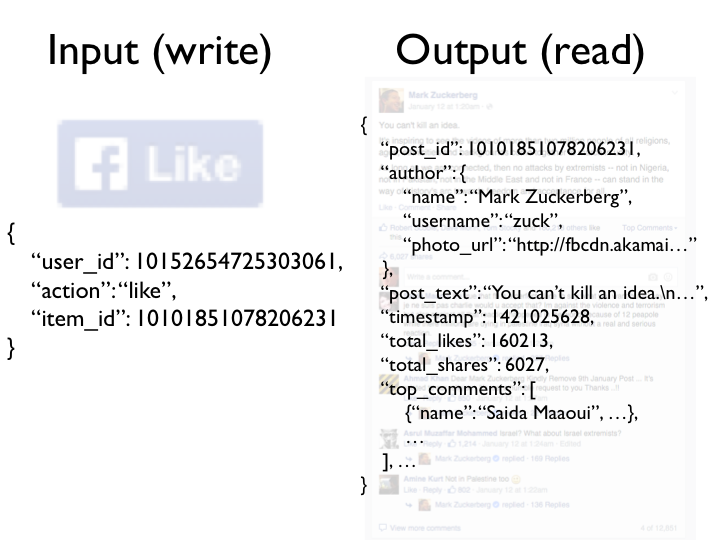

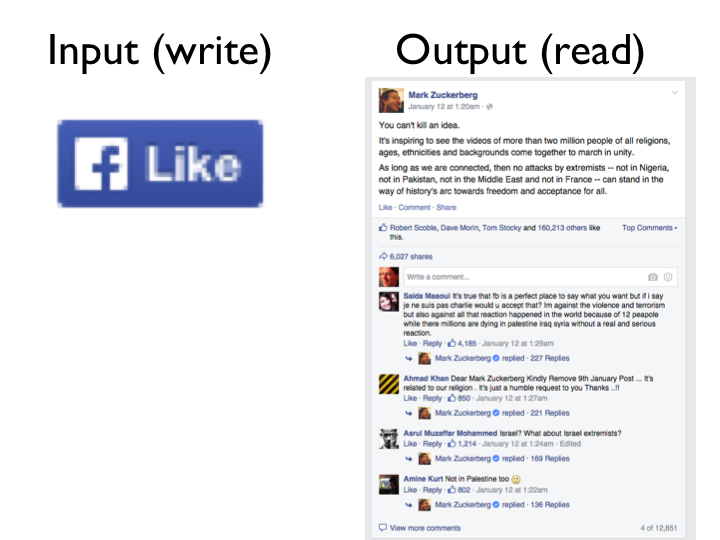

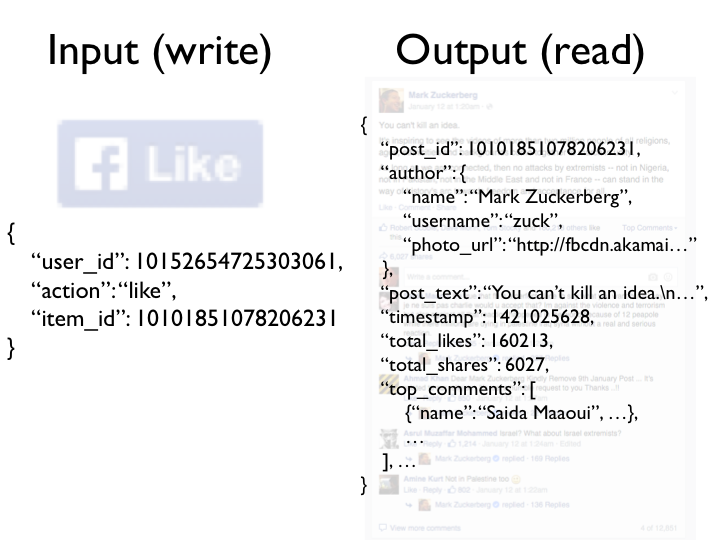

Another example: take Facebook. It has many buttons that enable you to write something to Facebook’s

database, but a classic one is the “Like” button. When you click it, that generates an event, a fact

with a very simple structure: you (identified by your user ID) like (an action verb) some item

(identified by its ID).

However, if you look at the output side, reading something on Facebook, it’s incredibly complicated.

In this example we have a Facebook post which is not just some text, but also the name of the author

and his profile photo; and it’s telling me that 160,216 people like this update, of which three have

been especially highlighted (presumably because Facebook thinks that amongst the likers of this

update, these are the ones I am most likely to know); it’s telling me that there are 6,027 shares

and 12,851 comments, of which the top 4 comments are shown (clearly some kind of comment ranking is

happening here); and so on.

There must be some translation process happening here, which takes the very simple events as input,

and produces the massively complex and personalized output structure. You can’t even conceive what

the database query would look like to fetch all the information in that Facebook update. There is no

way they could efficiently query all of that on the fly, not with over 100,000 likes. Clever caching

is absolutely essential if you want to build something like this.

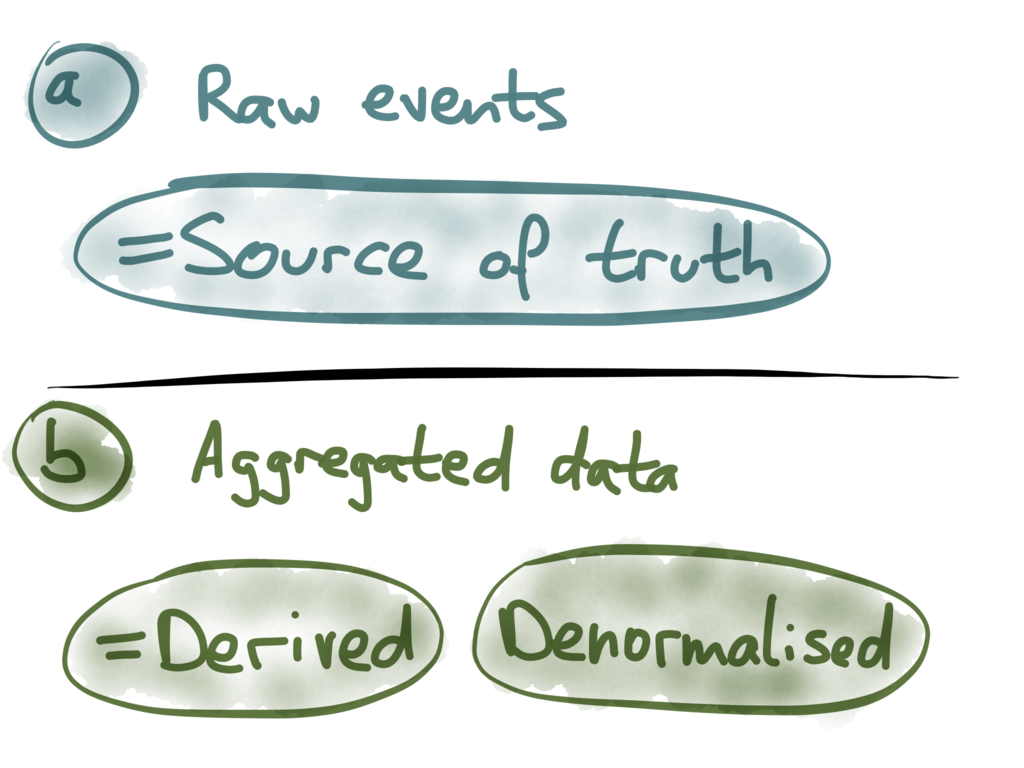

From the Twitter and Facebook examples we can see a certain pattern: the input events, corresponding

to the buttons in the user interface, are quite simple. They are immutable facts, we can simply

store them all, and we can treat them as the source of truth.

Everything that you can see on a website, i.e. everything that you read from the database, can be

derived from those raw events. There is a process which derives those aggregates from the raw

events, and which updates the caches when new events come in, and that process is entirely

deterministic. You could, if necessary, re-run it from scratch: if you feed in the entire history of

everything that ever happened on the site, you can reconstruct every cache entry to be exactly as it

was before. The database you read from is just a

cached view of the event log.

The beautiful thing about this separation between source of truth and caches is that in your caches,

you can denormalize data to your heart’s content. In regular databases, it is often considered best

practice to normalize data, because if something changes, you then only have to change it one place.

Normalization makes writes fast and simple, but means you have to do more work (joins) at read time.

In order to speed up reads, you can denormalize data, i.e. duplicate information in various places

so that it can be read faster. The problem is now that if the original data changes, all the places

where you copied it to also need to change. In a typical database, that’s a nightmare, because you

may not know all the places where something has been copied. But if your caches are built from your

raw events using a repeatable process, you have much more freedom to denormalize, because you know

what data is flowing where.

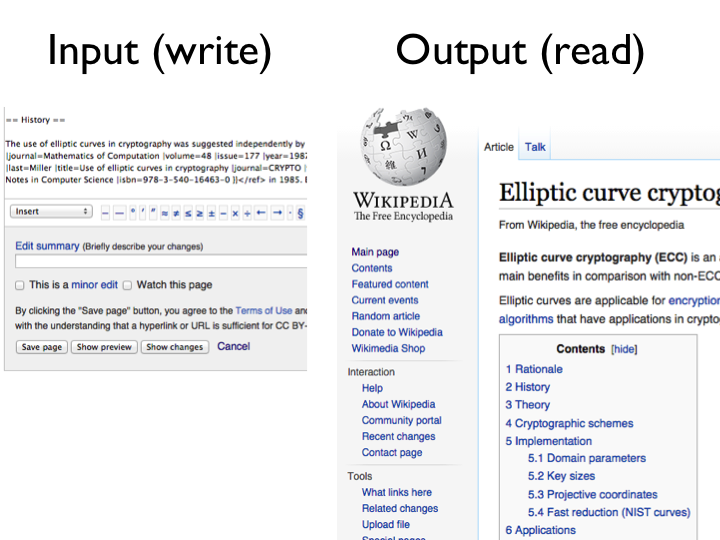

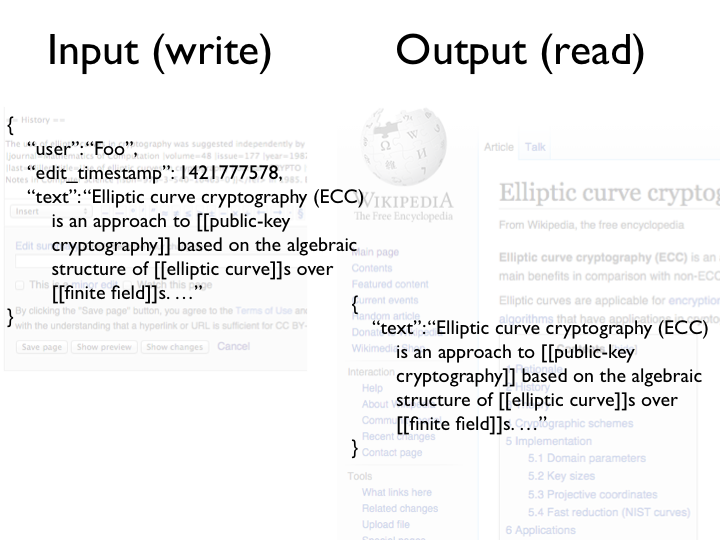

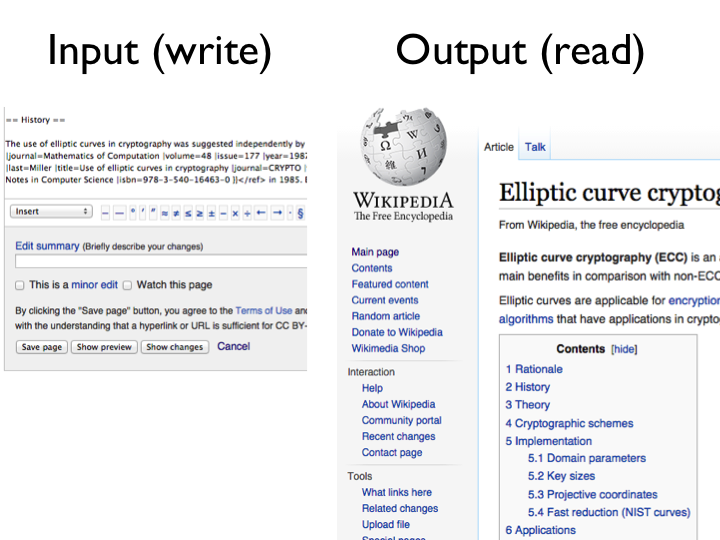

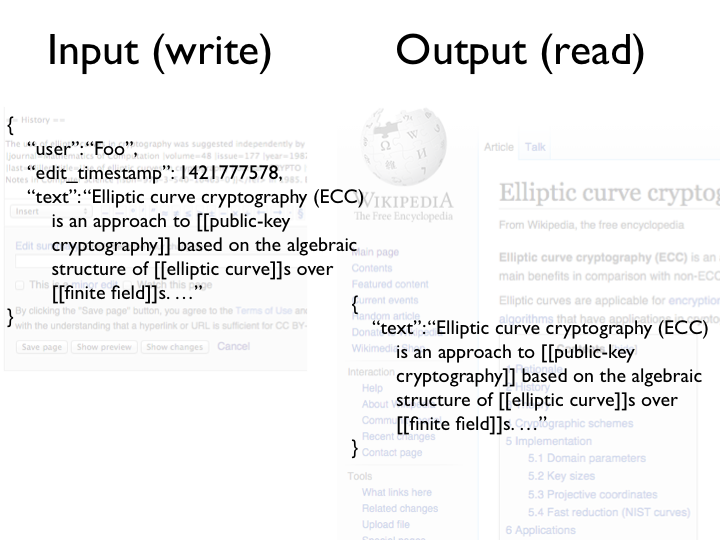

Another example: Wikipedia. This is almost a counter-example to Twitter and Facebook, because on

Wikipedia the input and the output are almost the same.

When you edit a page on Wikipedia, you get a big text field containing the entire page content

(using wiki markup), and when you click the save button, it sends that entire page content back to

the server. The server replaces the entire page with whatever you posted to it. When someone views

the page, it returns that same content back to the user (formatted into HTML).

So, in this case, the input and the output are the same. What would event sourcing mean in this

case? Would it perhaps make sense to represent a write event as a diff, like a patch file, rather

than a copy of the entire page? It’s an interesting case to think about. (Google Docs works by

continually applying diffs at a character granularity — effectively an event per keystroke.)

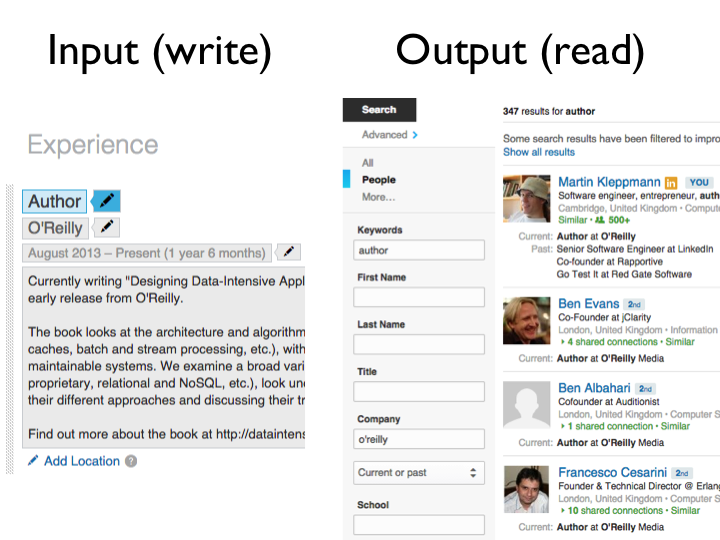

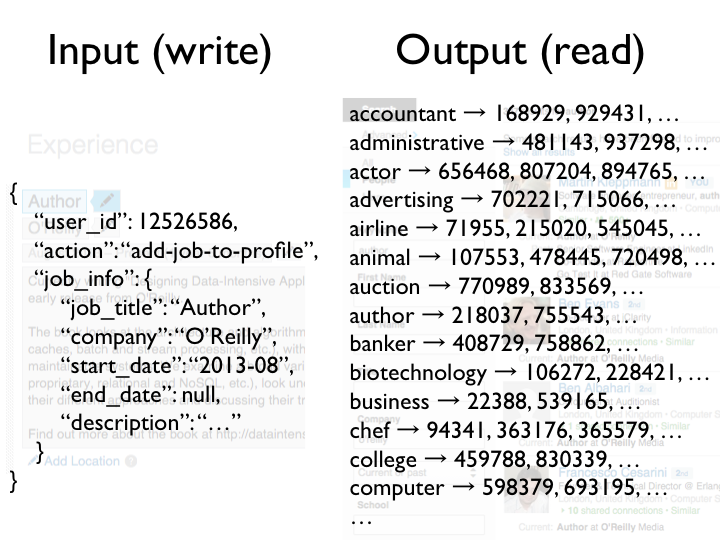

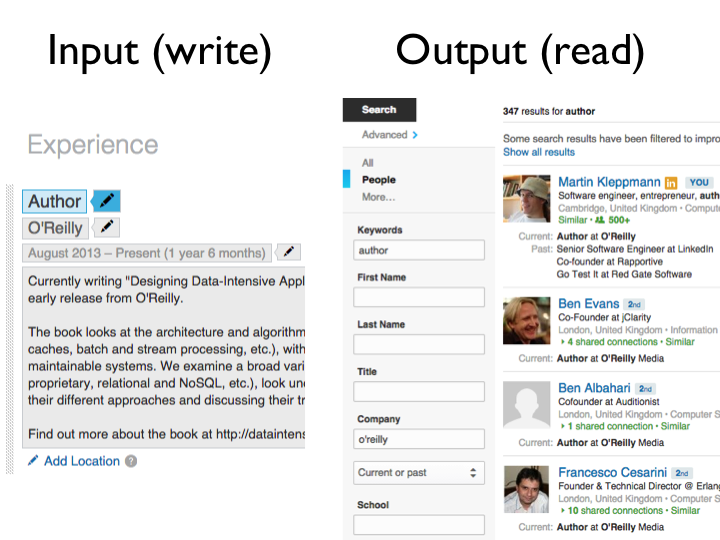

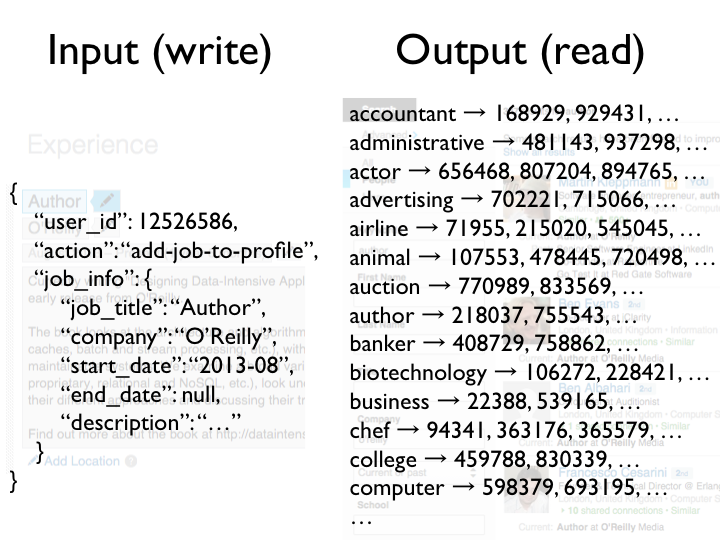

Final example: LinkedIn. Say you update your LinkedIn profile, and add your current job, which

consists of a job title, a company, and some text. Again, the edit event for writing to the database

is very simple.

There are various ways how you can read this data, and in this example, let’s look at the search

feature. On the output side, one way you can read LinkedIn’s database is by typing some keywords and

maybe a company name into a search box, and find all the people matching those criteria.

How is that implemented? Well, in order to search, you need a full-text index, which is essentially

a big dictionary — for every keyword, it tells you the IDs of all the profiles that contain the

keyword. This search index is another aggregate structure, and whenever some data is written to the

database, this structure needs to be updated with the new data.

So for example, if I add my job “Author at O’Reilly” to my profile, the search index must now be

updated to include my profile ID under the entries for “author” and “o’reilly”. The search index is

just another kind of cache. It also needs to be built from the source of truth (all the profile

edits that have ever occurred) and it needs to be updated whenever a new event occurs (someone edits

their profile).

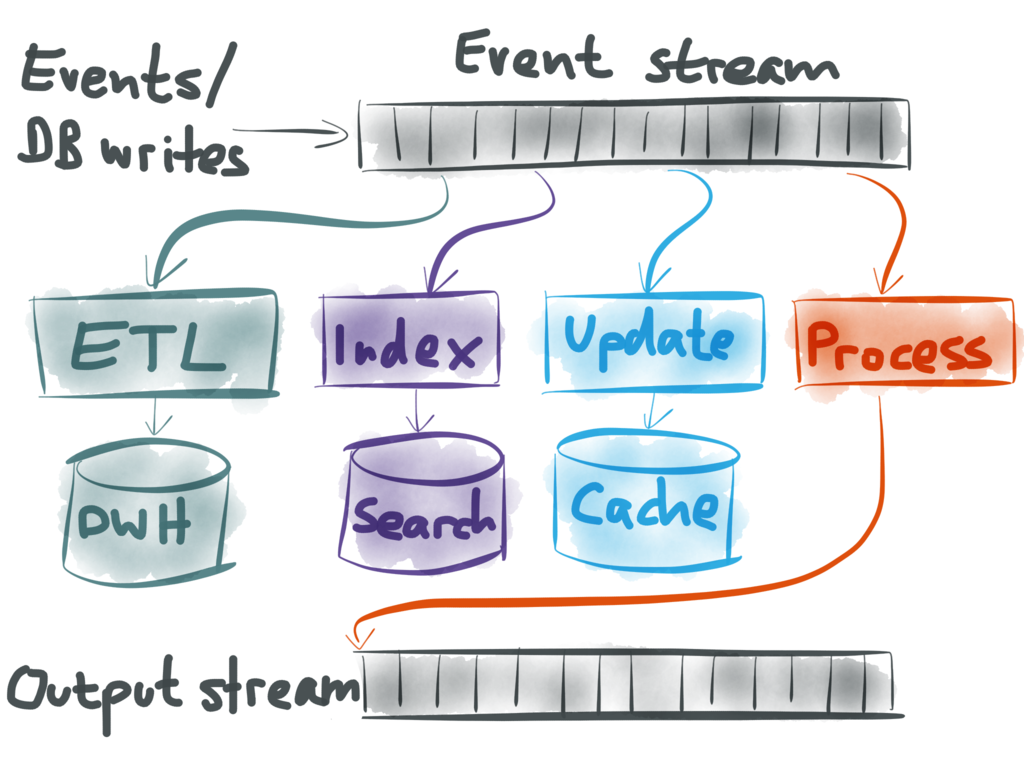

Now, returning to stream processing. I first described how you might build something like Google

Analytics, and compared storing raw page view events versus aggregated counters, and discussed how

you can maintain those aggregates by consuming a stream of events.

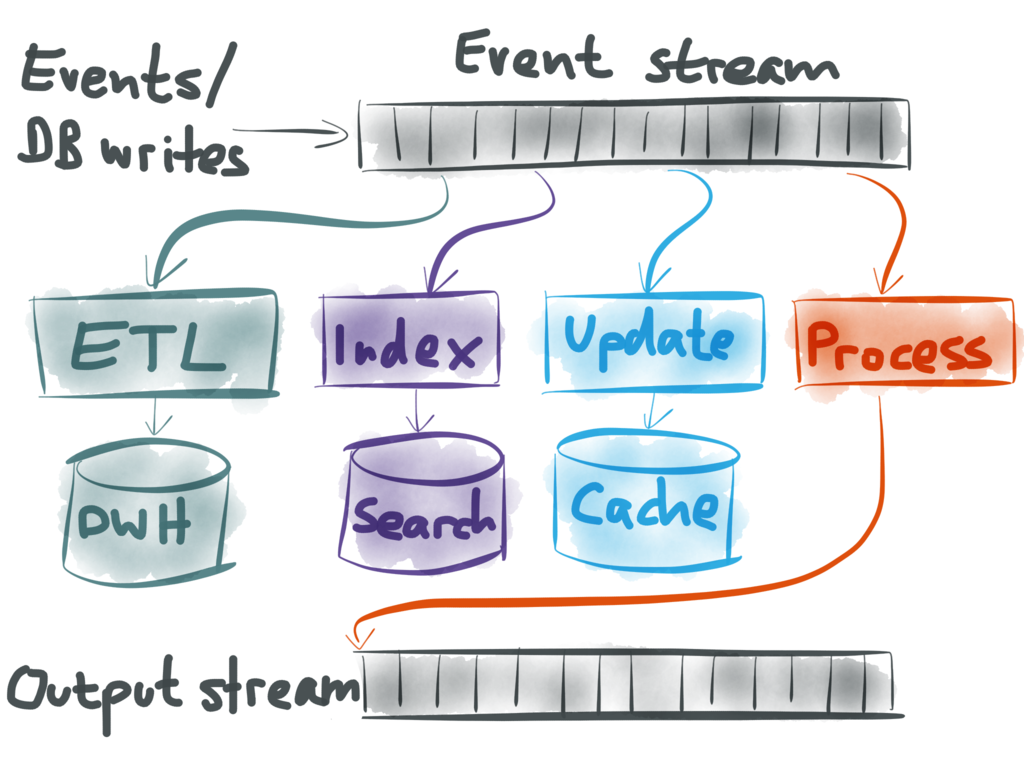

I then explained event sourcing, which applies a similar approach to databases: treat all the

database writes as a stream of events, and build aggregates (views, caches, search indexes) from

that stream. Once you have that event stream, you can do many great things with it:

- You can take all the raw events, perhaps transform them a bit, and load them into a big data

warehouse where analysts can query the data to their heart’s content.

- You can update full-text search indexes, so that when a user hits the search box, they are

searching an up-to-date version of the data.

- You can invalidate or refill any caches, so that reads can be served from fast caches while also

making sure that the data in the cache remains fresh.

- And finally, you can even take one event stream, and process it in some way (perhaps joining a few

streams together) to create a new output stream. This way, you can plug the output of one system

into the input of another system. This is a very powerful way of building complex applications

cleanly.

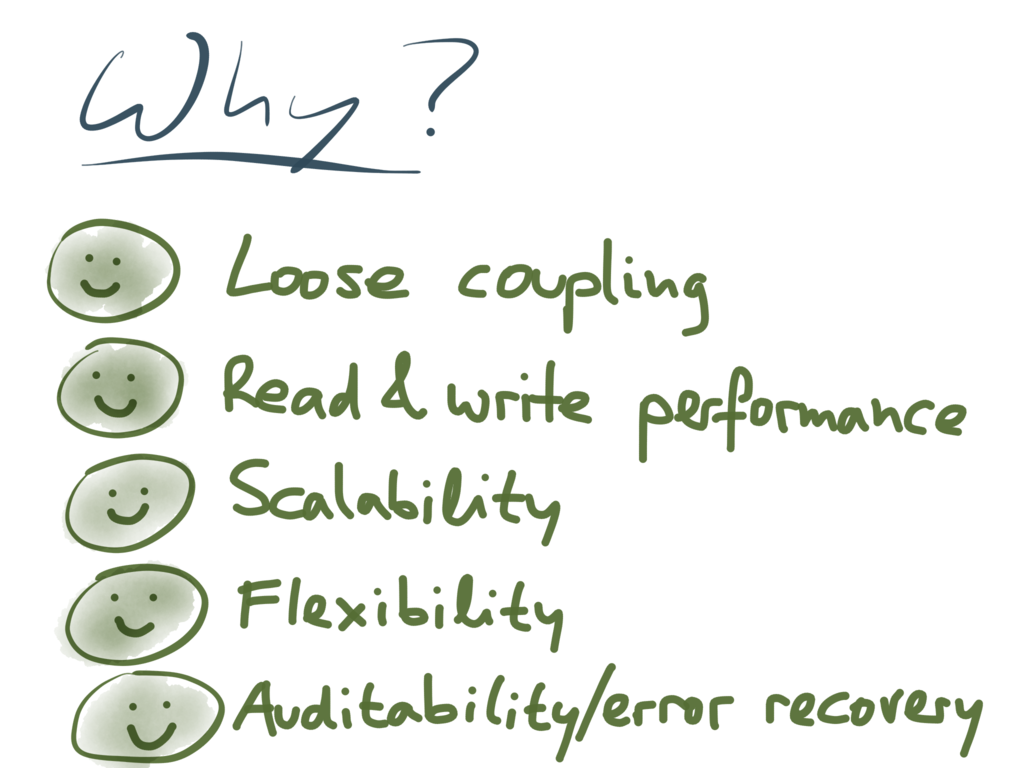

Moving to an event-sourcing-like approach for databases is a big change from the way that databases

have traditionally been used (where you can update and delete data at will). Why would you want to

go to all that effort of changing the way you do things? What’s the benefit of using append-only

streams of immutable events?

Several reasons:

- Loose coupling. If you write data to the database in the same schema as you use for reading,

you have tight coupling between the part of the application doing the writing (the “button”) and

the part doing the reading (the “screen”). We know that loose coupling is a good design principle

for software. By separating the form in which you write and read data, and by explicitly

translating from one to the other, you get much looser coupling between different parts of your

application.

- Read and write performance. The decades-old debate over normalization (faster writes) vs.

denormalization (faster reads) exists only because of the assumption that writes and reads use the

same schema. If you separate the two, you can have fast writes and fast reads.

- Event streams are great for scalability, because they are a simple abstraction (comparatively

easy to parallelize and scale across multiple machines), and because they allow you to decompose

your application into producers and consumers of streams (which can operate independently, and can

take advantage of more parallelism in hardware).

- Flexibility and agility. Raw events are so simple and obvious that a “schema migration”

doesn’t really make sense (you may just add a new field from time to time, but you don’t usually

need to rewrite historic data into a new format). On the other hand, the ways in which you want to

present data to users are much more complex, and may be continually changing. If you have an

explicit translation process between the source of truth and the caches that you read from, you

can experiment with new user interfaces by just building new caches using new logic, running the

new system in parallel with the old one, gradually moving people over from the old system, and

then discarding the old system (or reverting to the old system if the new one didn’t work). Such

flexibility is incredibly liberating.

- Finally, error scenarios are much easier to reason about if data is immutable. If something

goes wrong in your system, you can always replay events in the same order, and

reconstruct exactly what happened (especially

important in finance, where auditability is crucial). If you deploy buggy code that writes bad

data to a database, you can just re-run it after you fixed the bug, and thus correct the outputs.

Those things are not possible if your database writes are destructive.

Finally, let’s talk about how you might put these ideas into practice.

I should point out that in reality, database writes often already do have a certain event-like

immutable quality. The write-ahead log

that exists in most databases is essentially an event stream of writes, although it’s very specific

to a particular database. The MVCC mechanism in databases like PostgreSQL, MySQL’s InnoDB and

Oracle, and the append-only B-trees of CouchDB, Datomic and LMDB are examples of the same thinking:

it’s better to structure writes as an append-only log than to perform destructive overwrites.

However, here we’re not talking about the internals of storage engines, but about using event

streams at the application level.

Some databases such as Event Store have oriented themselves

specifically at the event sourcing model, and some people have implemented event sourcing on top of

relational databases. Those may be viable solutions if you’re operating at fairly small scale.

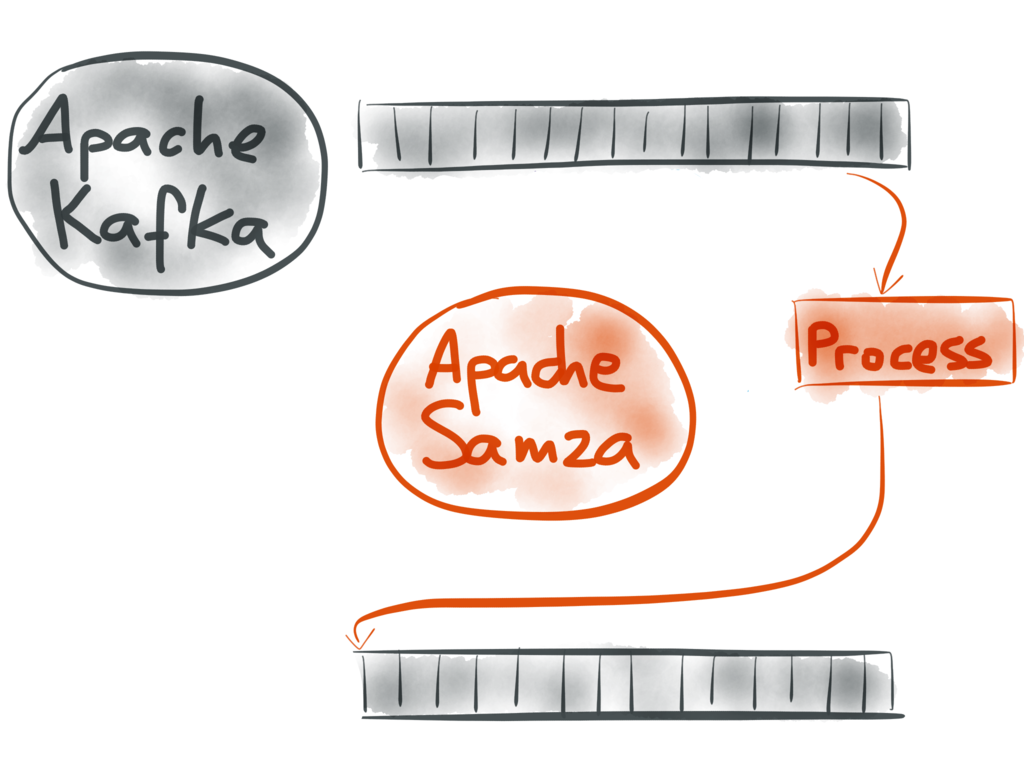

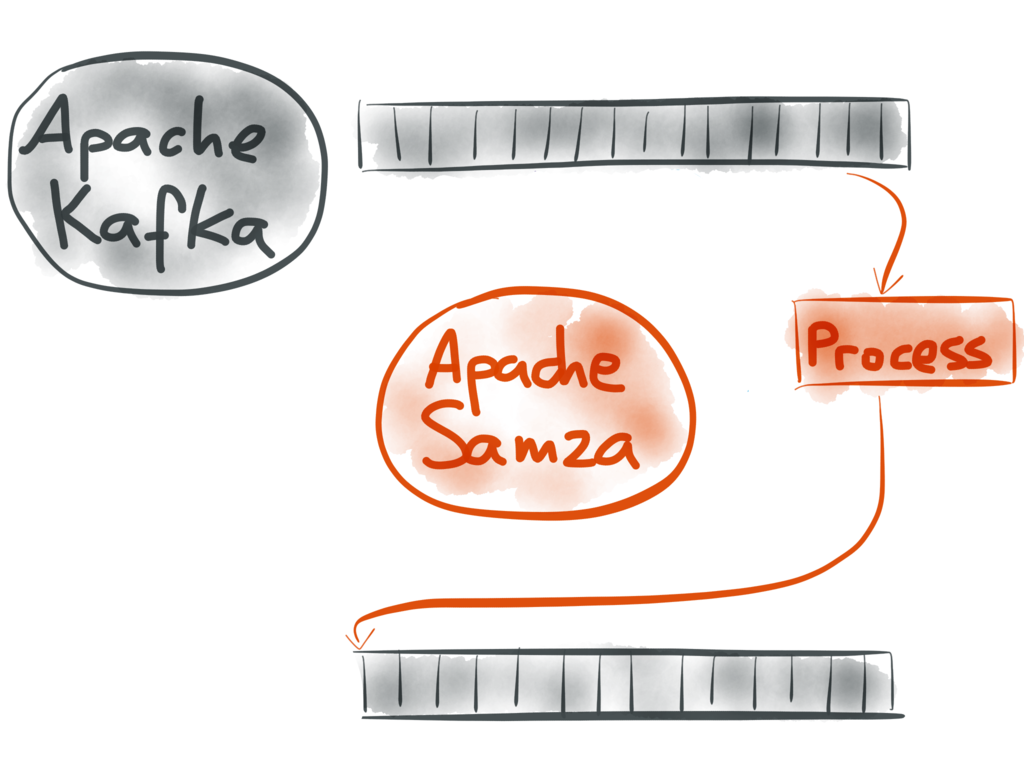

The systems I have worked with most are Apache Kafka and

Apache Samza. They are open source projects that originated at LinkedIn,

and now have a big community around them. Kafka is a message broker, like a publish-subscribe

message queue, which supports event streams with many millions of messages per second, durably

stored on disk and replicated across multiple machines.

Samza is the processing counterpart to Kafka: a framework which lets you write code to consume input

streams and produce output streams, and it handles stuff like deploying your code to a cluster and

recovering from failures.

I would definitely recommend Kafka as a system for high-throughput reliable event streams. On the

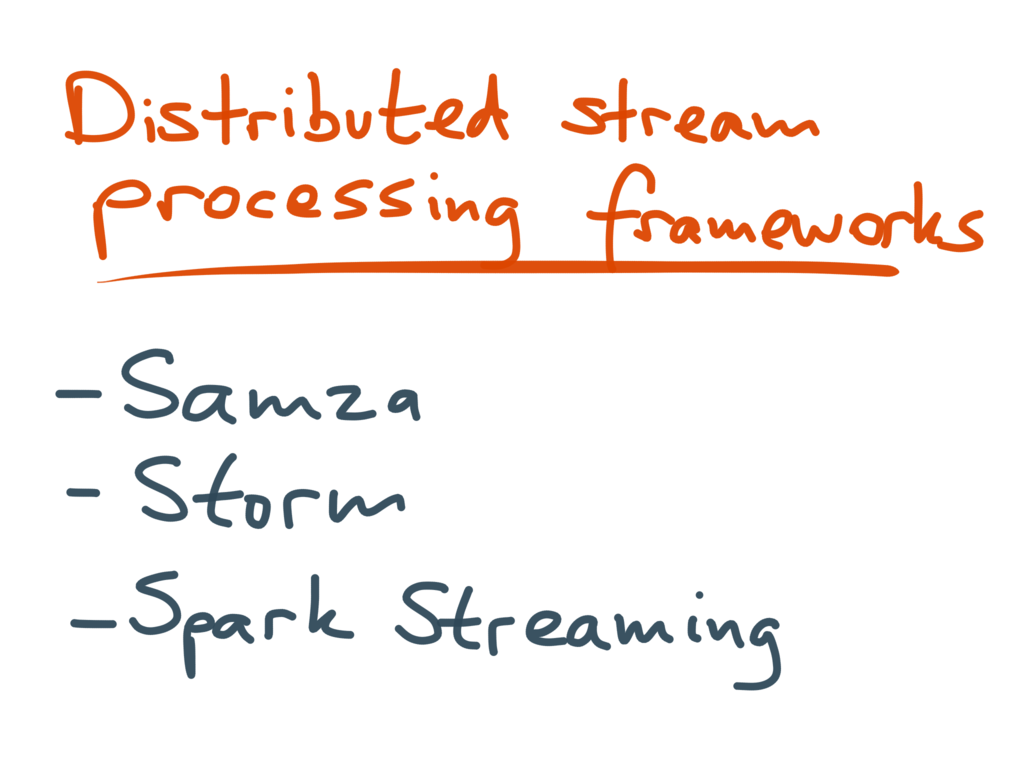

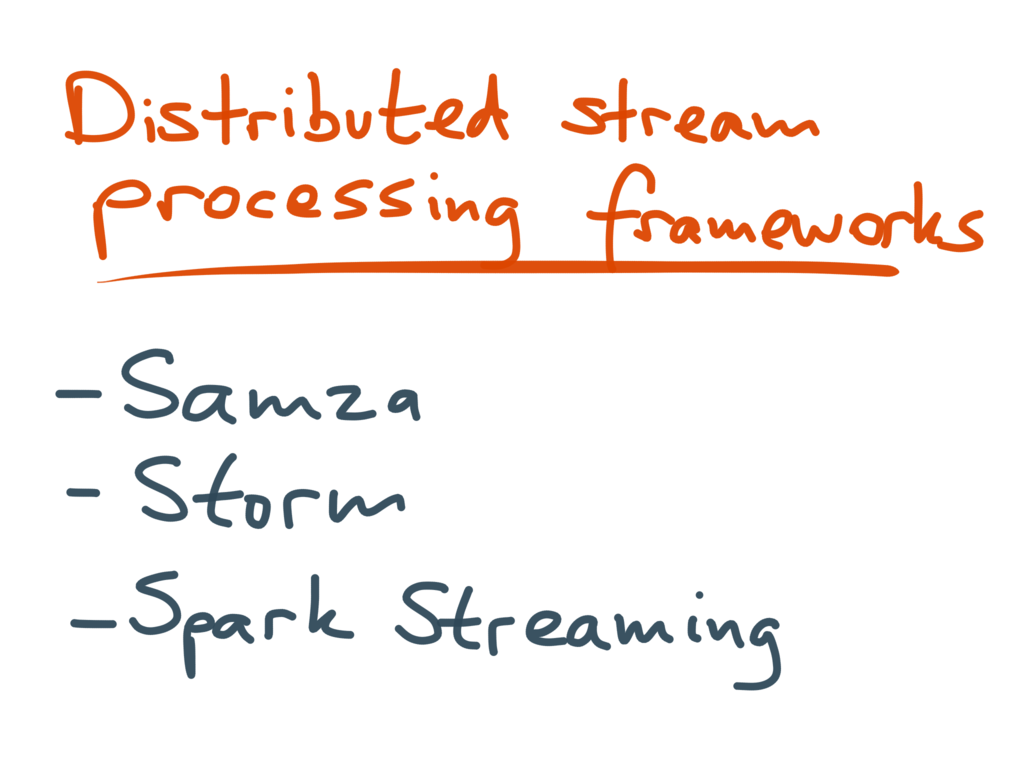

processing side, there are a few choices: Samza,

Storm and Spark Streaming are the

most popular stream processing frameworks. They all allow you to run your stream processing code

distributed across multiple machines.

There are interesting design differences (pros and cons) between these three frameworks, which

I don’t have time to go into here. You can read up a detailed comparison between them in the

Samza documentation.

And yes, I also think it’s funny that they all start with the letter S.

Today’s distributed stream processing systems have come out of internet companies (Samza from

LinkedIn, Storm from Backtype/Twitter). Arguably, they have their roots in stream processing

research from the early 2000s (TelegraphCQ,

Borealis, etc), which originated from a relational

database background. Just as NoSQL datastores stripped databases down to a minimal feature set,

modern stream processing systems look quite stripped-down compared to the earlier research.

The modern stream processing frameworks (Samza, Storm, Spark Streaming) are mostly concerned with

low-level matters: how to scale processing across multiple machines, how to deploy a job to

a cluster, how to handle faults (crashes, machine failures, network outages), and how to achieve

reliable performance in a

multi-tenant environment. The APIs they

provide are quite low-level (e.g. a callback that is invoked for every message). They look much more

like MapReduce and less like a database. They are more interested in reliable operation than in

fancy features.

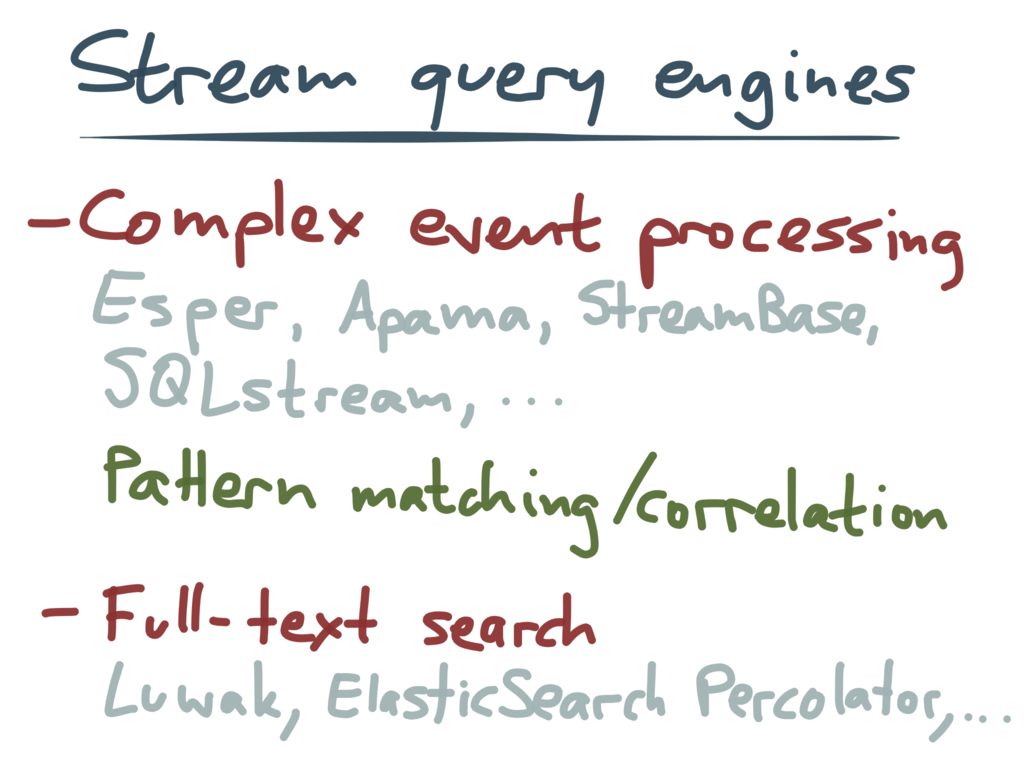

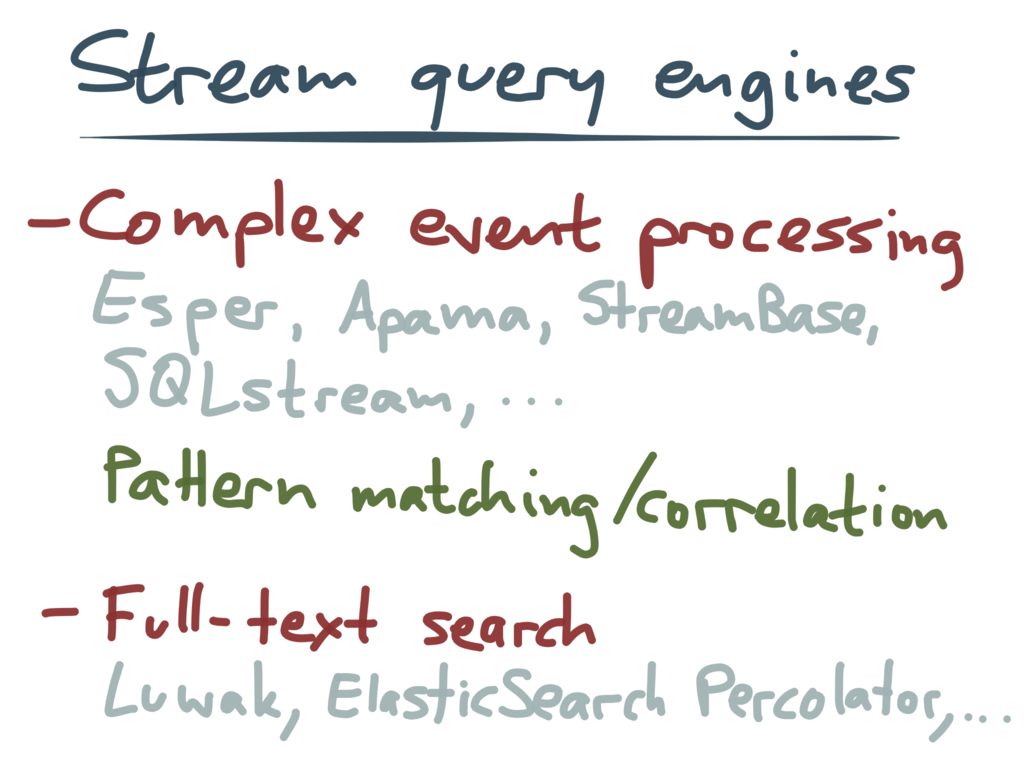

By contrast, there is also some work on high-level query languages for stream processing,

and Complex Event Processing is especially worth mentioning. It originated in 1990s research on

event-driven simulation,

and most CEP products are commercial, expensive enterprise software (only

Esper is free/open source, and it’s limited to running on a single

machine).

With CEP, you write queries or rules that match certain patterns in the events. They are comparable

to SQL queries (which describe what results you want to return from a database), except that the CEP

engine continually searches the stream for sets of events that match the query and notifies you

(generates a “complex event”) whenever a match is found. This is useful for fraud detection or

monitoring business processes, for example.

For use cases that can be easily described in terms of a CEP query language, such a high-level

language is much more convenient than a low-level event processing API. On the other hand,

a low-level API gives you more freedom, allowing you to do a wider range of things than a query

language would let you do. Also, by focussing their efforts on scalability and fault tolerance,

stream processing frameworks provide a solid foundation upon which query languages can be built.

A related idea is doing full-text search on streams, where you register a search query in advance,

and then get notified whenever an event matches your query. We’ve done some

experimental work with

Luwak in this area, but it’s still very new.

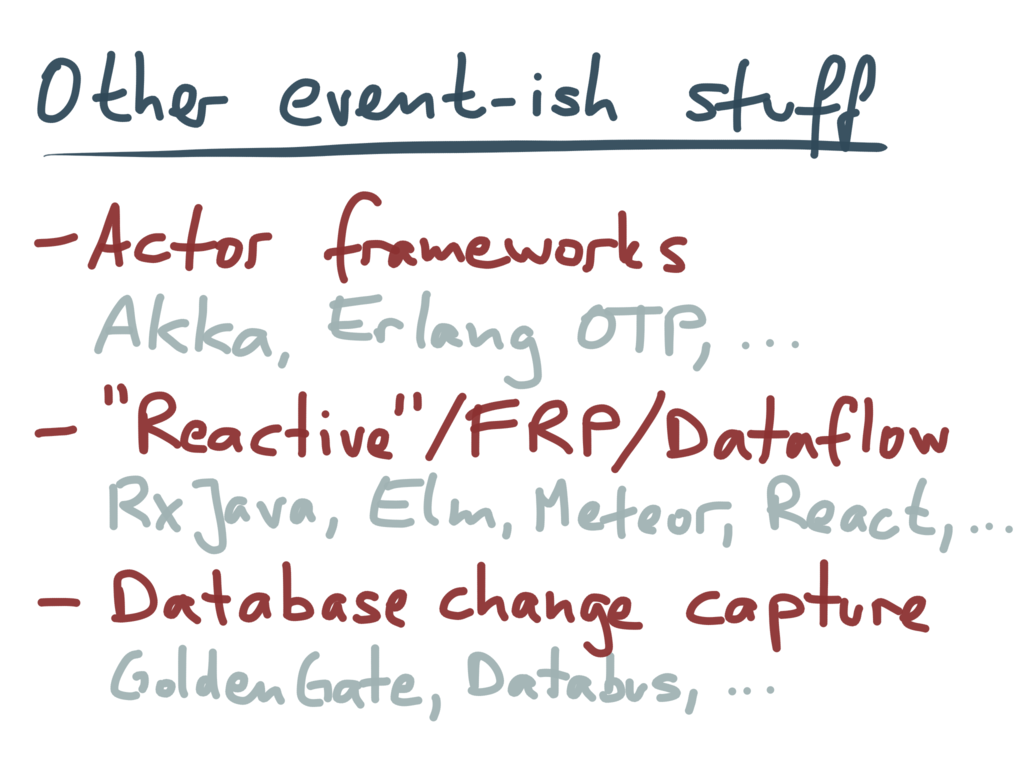

Finally, there are a lot of other things that are somehow related to stream processing. Going into

laundry-list mode, here is a brief summary:

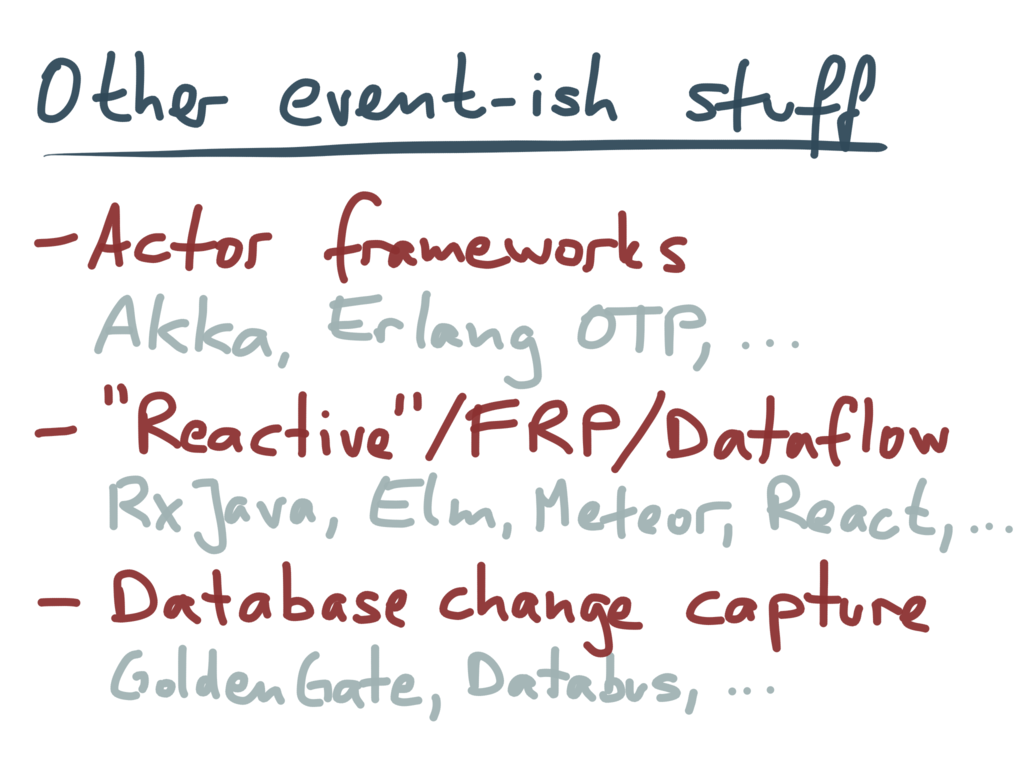

- Actor frameworks such as Akka, Orleans and Erlang OTP are also based on streams of immutable

events. However, they are primarily a mechanism for concurrency, less a mechanism for data

management. Some actor frameworks do have a distributed component, so you could build

a distributed stream processing framework on top of actors. However, it’s worth looking carefully

at the fault-tolerance guarantees and failure modes of these systems: many don’t provide

durability, for example.

- There’s a lot of buzz around “reactive”, which seems to encompass a quite loosely-defined

set of ideas. My impression is that there is some good work

happening in dataflow languages and functional reactive programming (FRP), which I see as mostly

about bringing event streams to the user interface, i.e. updating the user interface when some

underlying data changes. This is a natural counterpart to event streams in the data backend.

- Finally, change data capture (CDC) means using an existing database in the familiar way, but

extracting any inserts, updates and deletes into a stream of data change events which other

applications can consume. This is a great migration path towards a stream-oriented architecture,

and I’ll be talking and writing more about CDC in future.

I hope this talk helped you make some sense of the many facets of stream processing!

Martin Kleppmann is a software engineer and entrepreneur. He is

a committer on Apache Samza and author of the upcoming O’Reilly book

Designing Data-Intensive Applications. He’s

@martinkl on Twitter.

If you found this post useful, please

support me on Patreon

so that I can write more like it!

To get notified when I write something new,

follow me on Bluesky or

Mastodon,

or enter your email address:

I won't give your address to anyone else, won't send you any spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.