The Investigatory Powers Bill would increase cybercrime

Published by Martin Kleppmann on 10 Nov 2015.

As widely reported, the UK government proposed the draft of a new Investigatory Powers

Bill last week. There has been much discussion of the bill already, but there are some

important questions which I have not yet seen addressed.

These open questions raise serious concerns about the effects that the proposed law would have on

ordinary citizens. In this article I argue that if the bill is passed in its current form, its

effect will be exactly the opposite of that intended: it would leave citizens more exposed to the

risks of crime and terrorism, and not reduce those risks as intended.

Background of the bill

The stated purpose of the Investigatory Powers Bill is to help fight crime and terrorism – in other

words, to uphold the rule of law and to keep us safe from aggression. If people break the law or

harm citizens (for example through paedophilia, murder, or acts of terrorism), our law enforcement

services require the means to find the perpetrators and hold them responsible. This is an important

public service: a country with ineffective law enforcement would quickly become dysfunctional.

There is a well-known tension between the ability of law enforcement services to get the information

they require to find and convict criminals, and the basic human right of privacy for

innocent citizens. In order to do their job, the police and the intelligence services must

necessarily intrude on individuals’ privacy to some degree. For us as a society, it is important

that we decide how much privacy we are collectively willing to sacrifice for the

sake of helping law enforcement services do their job.

However, this article is not about the tension between security and privacy – it is only about

security. The Investigatory Powers Bill is supposed to increase our security by giving law

enforcement services the tools they need to catch criminals and terrorists. I will argue that, in

fact, the proposed bill harms our security by making us more vulnerable to attacks by criminals

and terrorists.

People who defend surveillance often say that a loss of privacy is a price that many people are

willing to pay for the sake of increased safety. However, what if the surveillance

measures actually make people less safe? Even if you do not care about privacy, you should be

strongly opposed to this bill, because it vastly increases the risks of cybercrime, as explained

below.

Encrypted communication

Encryption ensures that your information can only be read by the correct recipient, and not by any

random bystander. Whenever you send information over the internet, if that information has any

value whatsoever, it should be encrypted – otherwise anyone (e.g. people using the same coffee shop

wifi as you) can trivially steal it. Thus, almost all websites use encryption whenever passwords,

credit card numbers, online banking information, or similar sensitive information is involved. If we

didn’t encrypt this information, fraud and identity theft would be rampant. Encryption is a basic

necessity for the internet.

However, encryption can be applied at different levels. For example, in a chat or telephony app,

there are two options:

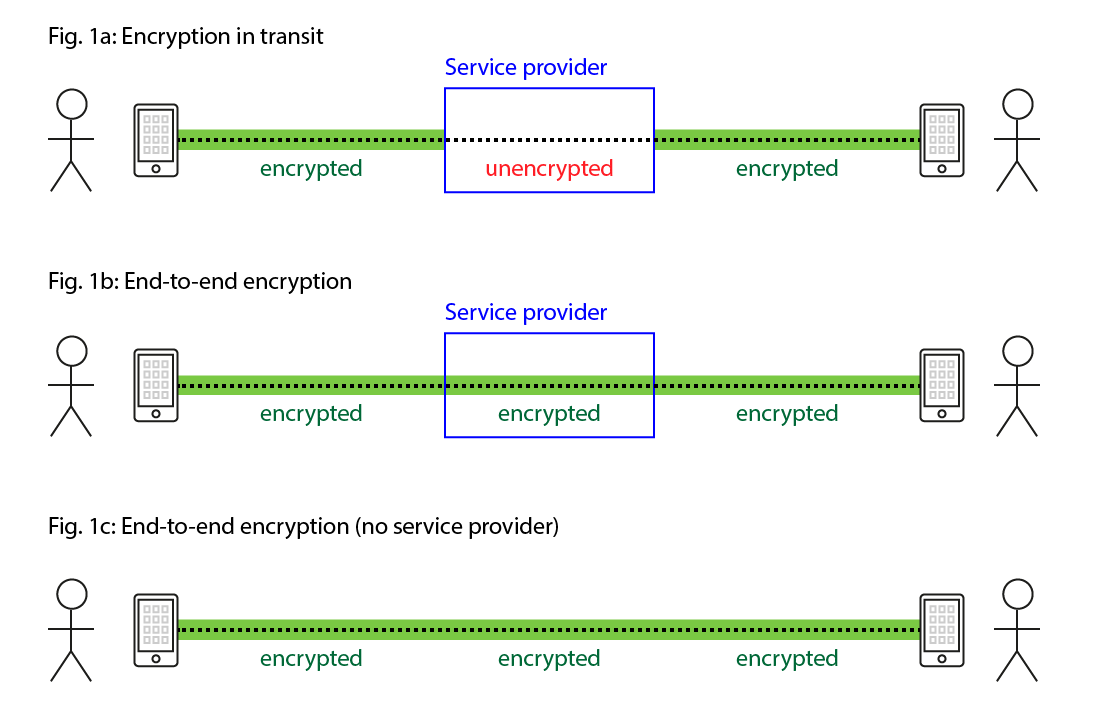

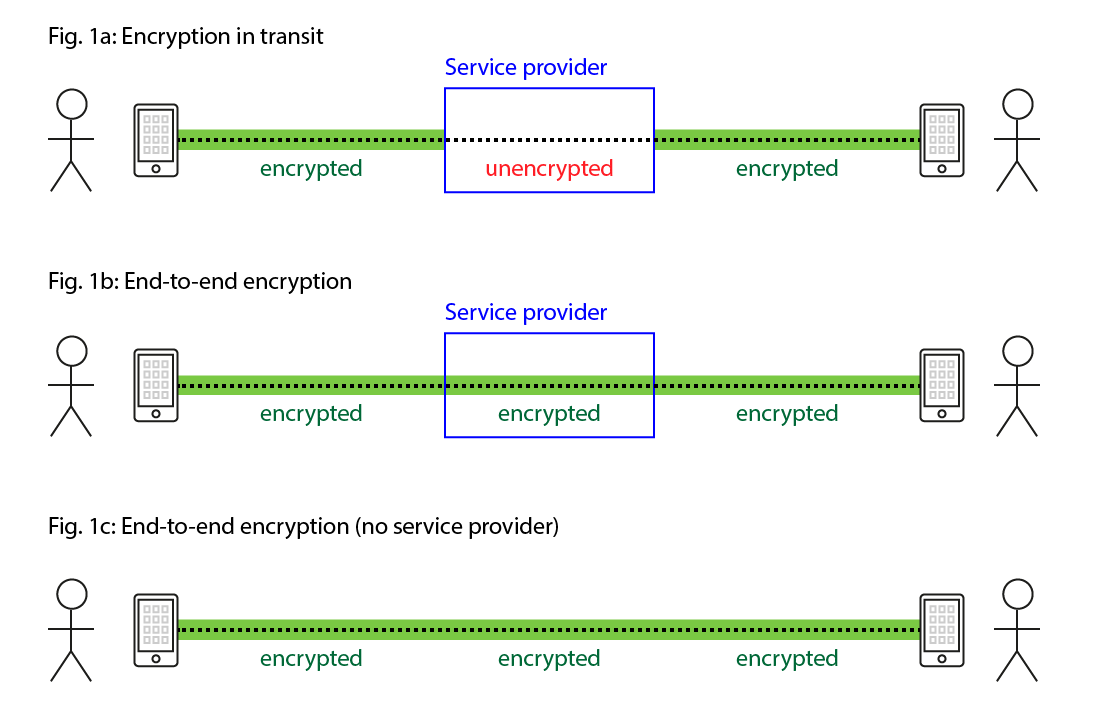

- Encryption in transit: In this case, the data is encrypted as it is transmitted between your

device and the service provider (e.g. a mobile network operator or a social network), but the

service provider handles the data in unencrypted form. This is illustrated in Figure 1a. In this

case, the service provider is able to read all of the communication, and you need to trust them to

safeguard your information appropriately.

- End-to-end encryption: In this case, data is encrypted all the way between you and the person

you’re talking to. The service provider only passes on the messages, but it cannot see what you

are talking about (Figure 1b). There may not even be a service provider, because anybody can

write their own app that communicates over the internet, without requiring a centrally managed

service (Figure 1c).

If law enforcement decides to investigate you, and encryption in transit is used, that makes life

very easy for law enforcement: they can serve a warrant to the service provider, and get them to

wiretap your communication without you ever knowing. With end-to-end encryption, surveillance is

still possible, but it’s more expensive: since the service provider cannot access the messages,

a warrant to the service provider is of no use. Instead, law enforcement must go to the people

communicating. For example, they can obtain a court order to seize your phone, or they can point

microphones and antennas at your house to listen to your communications, or they

can infiltrate the suspected gang.

Figure 1: The difference between encryption in transit and end-to-end encryption.

The value of end-to-end encryption

Although encryption in transit is widely used, it has serious security problems. For example, the

service provider could be hacked by an adversary, or compromised by an insider, causing sensitive

information can be leaked. A fault in the service provider could cause data to be corrupted. For

these reasons, security experts are pushing towards widespread use of end-to-end encryption, which

reduces the exposure to such attacks.

The goal of end-to-end encryption is not to prevent legitimate access by law enforcement in cases

where it is justified for a criminal investigation. Rather, the goal is to defend systems against

adversaries who want to steal sensitive data or cause systems to malfunction. Such defence is

particularly critical in cases where human life is at stake, such as industrial control

systems, internet-connected cars, or medical data and devices. But

even in other domains, such as trade secrets and financial information in enterprises, in journalism

or in legal professions, it is crucial that sensitive information is adequately protected.

End-to-end encryption helps protect our own information against theft and manipulation by

adversaries – ranging from an individual disgruntled employee, to hostile foreign intelligence

services who may be spying or sabotaging for economic, political or military reasons. As more and

more aspects of the world are controlled by software, and as increasingly many devices

are connected to the internet, a cyberattack against weakly secured systems could have catastrophic

consequences. We will need all the defences we can get, and end-to-end encryption is going to be an

indispensable part of our security infrastructure.

Exceptional access to encrypted communication

On the other hand, end-to-end encryption makes life harder for law enforcement services, because

they cannot simply serve a warrant to the service provider in order to obtain the content of the

communication. For this reason, politicians have recently attacked end-to-end encryption; for

example, in a speech in January 2015, PM David Cameron said:

In our country, do we want to allow a means of communication between people which, even in

extremis, with a signed warrant from the home secretary personally, that we cannot read? […] The

question remains: are we going to allow a means of communications where it simply is not possible

to do that? My answer to that question is: no, we must not. The first duty of any government is to

keep our country and our people safe.

The proposed Investigatory Powers Bill is an attempt to cast into law this principle outlined by the

Prime Minister. In particular, it places a duty on communications service providers to allow law

enforcement agencies to intercept communication when served with a warrant – even if the service

provider is outside the UK (§31). It also requires service providers to assist with hacking devices

and removing encryption if compelled by an order from the home secretary (§189).

The bill and related guidance notes from the government do not explain how these rules might be put

into practice, but they have been interpreted as requiring services with end-to-end

encryption to have some kind of “backdoor” by which they can be broken, if required.

Other sources say that the government does not wish to ban end-to-end encryption,

but in that case it is not clear what they do want, since the Prime Minister has reiterated his

plea that terrorists, paedophiles and criminals must not be allowed a “safe space” online.

Security professionals have no interest in making life easy for terrorists, paedophiles and

criminals. However, any technology can be used for both good and bad purposes. The government has

not explained which technologies would comply with the new rules, and which technologies would

violate them – and the text of the bill itself is very vague and ambiguous.

If the bill requires communication services to have some mechanism of obtaining the content of the

communication in response to a warrant, that means the service must somehow retain the ability to

decrypt the data when required. Provisions for such exceptional access (e.g. key

escrow or backdoors) are normally avoided in encryption products, because they

introduce serious security problems.

Exceptional access is insecure

At first glance, it may seem reasonable to require that all encryption products must include

a provision for data to be decrypted by law enforcement agencies, as long as the decryption order is

protected with sufficient oversight to prevent abuse. However, on closer inspection, it turns out

that this proposal is deeply flawed.

The problem is laid out very clearly in a recent report, written by some of the biggest

names in cryptographic research and security engineering worldwide. To quote from the report:

Political and law enforcement leaders in the United States and United Kingdom … propose that

data storage and communications systems must be designed for exceptional access by law enforcement

agencies. These proposals are unworkable in practice, raise enormous legal and ethical questions,

and would undo progress on security at a time when Internet vulnerabilities are causing extreme

economic harm. As computer scientists with extensive security and systems experience, we believe

that law enforcement has failed to account for the risks inherent in exceptional access systems.

The report lays out in no uncertain terms: there is no known method for securely

providing law enforcement with exceptional access to systems with end-to-end encryption. Any method

that provides exceptional access immediately exposes the system to attacks by malicious parties,

rendering the protection of encryption essentially worthless.

Exceptional access would probably require that government departments have some kind of master keys

that allowed them to decrypt any communication if required. Those master keys would obviously have

to be kept extremely secret: if they were to become public, the entire security infrastructure of

the internet would crumble into dust.

How good are government agencies at keeping secrets? Even just in the last few months, the OPM

failed to protect millions of their own personnel records from hackers, the email

account of CIA Director John Brennan was hacked, and the master keys for TSA

locks were accidentally posted on the internet. The US Air Force has been accused of

accidentally broadcasting the launch codes for nuclear missiles over radio in the 1960s.

These incidents do not fill me with confidence that any government would be able to handle

cryptographic master keys securely.

If the law enforcement services can remotely break into the device of a suspect, then sooner or

later criminals will find ways to use the same mechanism to break into devices and steal or destroy

your personal data. They will know your location, and the PIN for your burglar alarm, so they will

have an easy time breaking into your house. There is simply no technical mechanism that will allow

legitimate access by law enforcement, and which is also unbreakable by people who want to do you

harm.

I’ll say it again, to be absolutely clear: any mechanism that can allow law enforcement legitimate

access to data can inevitably be abused by hostile foreign intelligence services, and even

technically sophisticated individuals, to break into systems and gain unauthorised access to the

same data. There is no known method for making this secure. If we add provisions for exceptional

access to encryption products, we are simply shooting ourselves in the foot.

Retention of browsing history

Another provision of the proposed Investigatory Powers Bill is that internet service providers

(ISPs) must retain a record of all the websites you visit (more specifically, all the IP addresses

you connect to) for one year. This appears to be another measure to weaken privacy while

strengthening security – but in fact, it is harmful to both privacy and security.

In order to maintain a record of every website you have visited in the last year, the ISP must store

that information somewhere accessible. Information that is stored somewhere accessible will sooner

or later be stolen by attackers. For example, just a few weeks ago, records of millions of TalkTalk

customers were stolen due to a SQL injection (one of the most easily

preventable security issues – the fact that TalkTalk was vulnerable to such a simple bug casts

serious doubt on their competence in elementary software engineering practices). If ISPs are

required to store your browsing history, it is only a matter of time before it is stolen.

And stolen browsing history is a security problem. After the website Ashley

Madison (which helps married people have an affair) was hacked, millions of its

users found their real name, home address, email address and credit card numbers spewed all over the

internet. It did not take long before blackmailers started using the data, threatening

users that their spouse would be informed unless a ransom was paid. Browsing history

retained by an ISP would carry the same blackmail risk.

The problem is not only extortion of money from the victims of blackmail, but also a security

problem. What if someone succeeds in blackmailing employees of an intelligence agency, or senior

civil servants, or a government official? If the victim fears for their reputation or repercussions

from the release of the sensitive information, the attacker gains power over the victim, which is

worrisome if the victim is in a position of power.

Increasingly, stolen personal information is being used for politically motivated blackmail and

intimidation. Even if you personally have never done anything embarrassing, and you have

nothing to hide, the fact that other people can be blackmailed is a risk to you if those people have

power over you.

“Give me six lines written by the most honest man in the world, and I will find enough in them to

hang him.” (Origin uncertain, attributed to Cardinal Richelieu.) Or, to give a more

modern equivalent: “We kill people based on metadata.” (Former CIA and NSA director Michael

Hayden.)

We must make systems more secure, not less

As David Cameron said, “the first duty of any government is to keep our country

and our people safe.” The proposed Investigatory Powers Bill is supposed to make us more safe by

giving great powers to the law enforcement services. However, in this article I have argued that the

bill would in fact make us significantly less safe, by making internet security systems vulnerable

to cyberattacks, and by increasing the risk of blackmail.

The proposed bill, as it stands now, is too vague to allow any serious technical analysis to take

place. With regard to encryption technologies, it fails to specify what is allowed and what is not.

But the Prime Minister’s repeated assertion that we “make sure we do not allow terrorists safe

spaces to communicate with each other” implies a worrisome weakening of security

technologies.

Nobody wants to give criminals a safe space in which they can operate. However, the technologies

that help protect industrial control systems, cars, medical devices, lawyers, journalists and

businesses against attacks by malicious parties are the same as the technologies behind which

criminals can hide. Any technology can be used for good and bad.

It is not possible to eliminate “safe spaces” for criminals without also eliminating security from

the computer systems that our daily lives depend on. I am worried that the Investigatory Powers Bill

would effectively mandate computer systems to be insecure, and thus leave our

infrastructure vulnerable to cyberattacks from people who want to do us harm.

According to the government’s own report, cybercrime is a Tier One risk to national

security, and already costs the UK £27bn per year. This is only going to get worse if we do not

improve the security of our computer systems. As internet-connected devices are increasingly used

for matters of life and death, the security of those devices becomes paramount, and breaches could

have catastrophic consequences. We need to do everything we can to strengthen the security of

those systems, not to weaken them.

I recognise that as systems become more secure, surveillance becomes more difficult for the

intelligence services. I acknowledge that secure communication systems may allow a terrorist plot or

a crime to succeed which may have been thwarted if surveillance was easy for law enforcement

services. But I argue that this risk is tiny compared to the risk of an

insecure, vulnerable infrastructure in which terrorist cyberattackers could wreak havoc.

Aside from the proposed bill’s disregard for civil liberties, even if we consider only the security

implications of the bill, it is deeply worrisome. As more technical details of the proposal become

clear, we must carefully examine to what extent they leave us less secure than we were before.

Thank you to Alastair Beresford and Diana Vasile for reviewing a draft of this article.

If you found this post useful, please

support me on Patreon

so that I can write more like it!

To get notified when I write something new,

follow me on Bluesky or

Mastodon,

or enter your email address:

I won't give your address to anyone else, won't send you any spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.