Writing a book: is it worth it?

Published by Martin Kleppmann on 29 Sep 2020.

My book, Designing Data-Intensive Applications, recently passed the

milestone of 100,000 copies sold. Last year, it was the second-best-selling book in O’Reilly’s

entire catalogue, second only to

Aurélien Géron’s machine learning book.

Machine learning is obviously a hot topic, so I am quite content with coming second to it! 😄

To me, the success of this book was totally unexpected: while I was writing it, I thought that it

was going to be a bit niche, and I set myself the goal of selling 10,000 copies over the lifetime

of the book. Having passed that goal tenfold, this seems like a good opportunity to look back and

reflect on the process. I don’t want to make this post too self-congratulatory, but rather I will

try to share some insights into the business of book-writing.

Is it financially worth it?

Most books make very little money for both authors and publishers, but then occasionally something

like Harry Potter comes along. If you are considering writing a book, I strongly recommend that

you estimate the value of your future royalties to be close to zero. Like starting a band with

friends and hoping to become rock stars, it’s difficult to predict in advance what will be a hit and

what will flop. Maybe this applies less to technical books than to fiction and music, but I suspect

that even with technical books, there are a small number of hits, and most books sell quite modest

numbers.

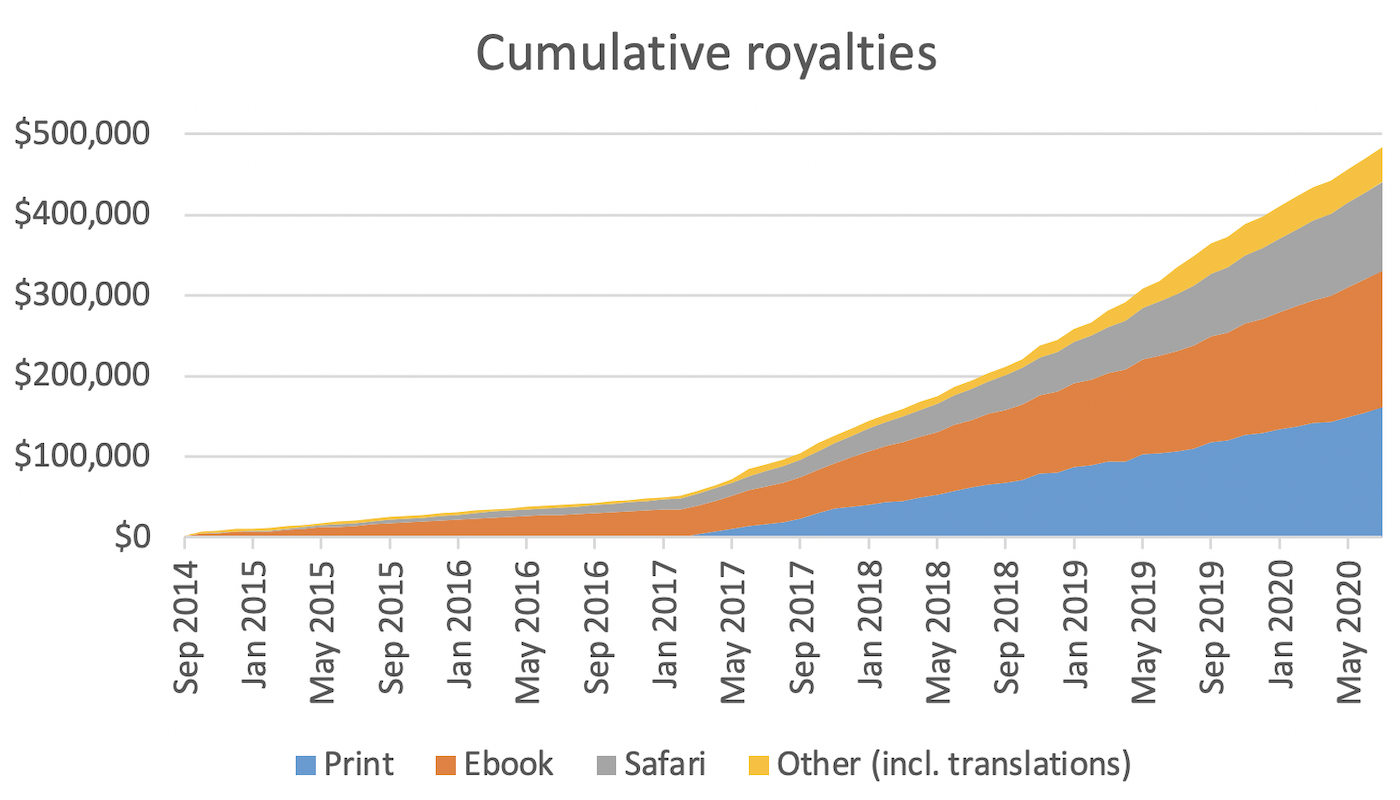

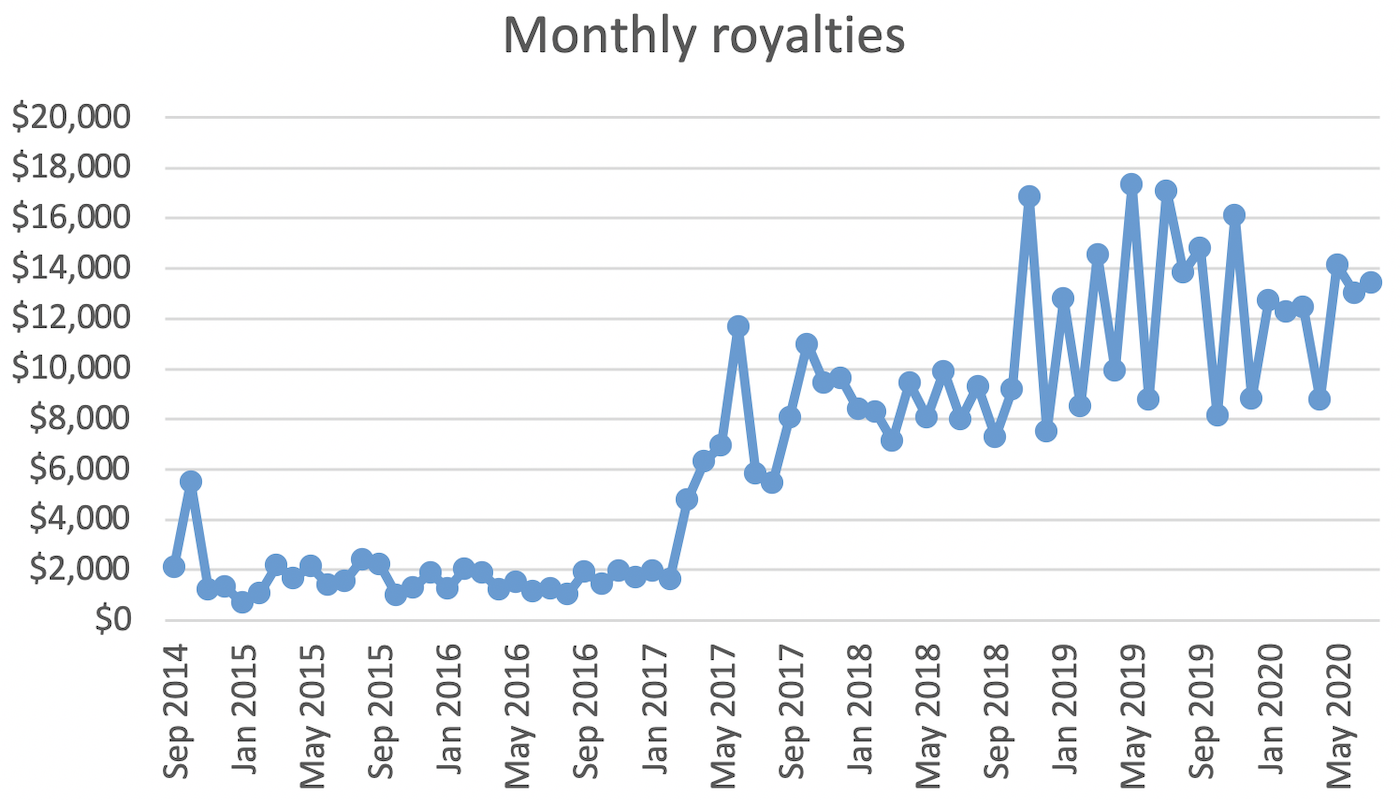

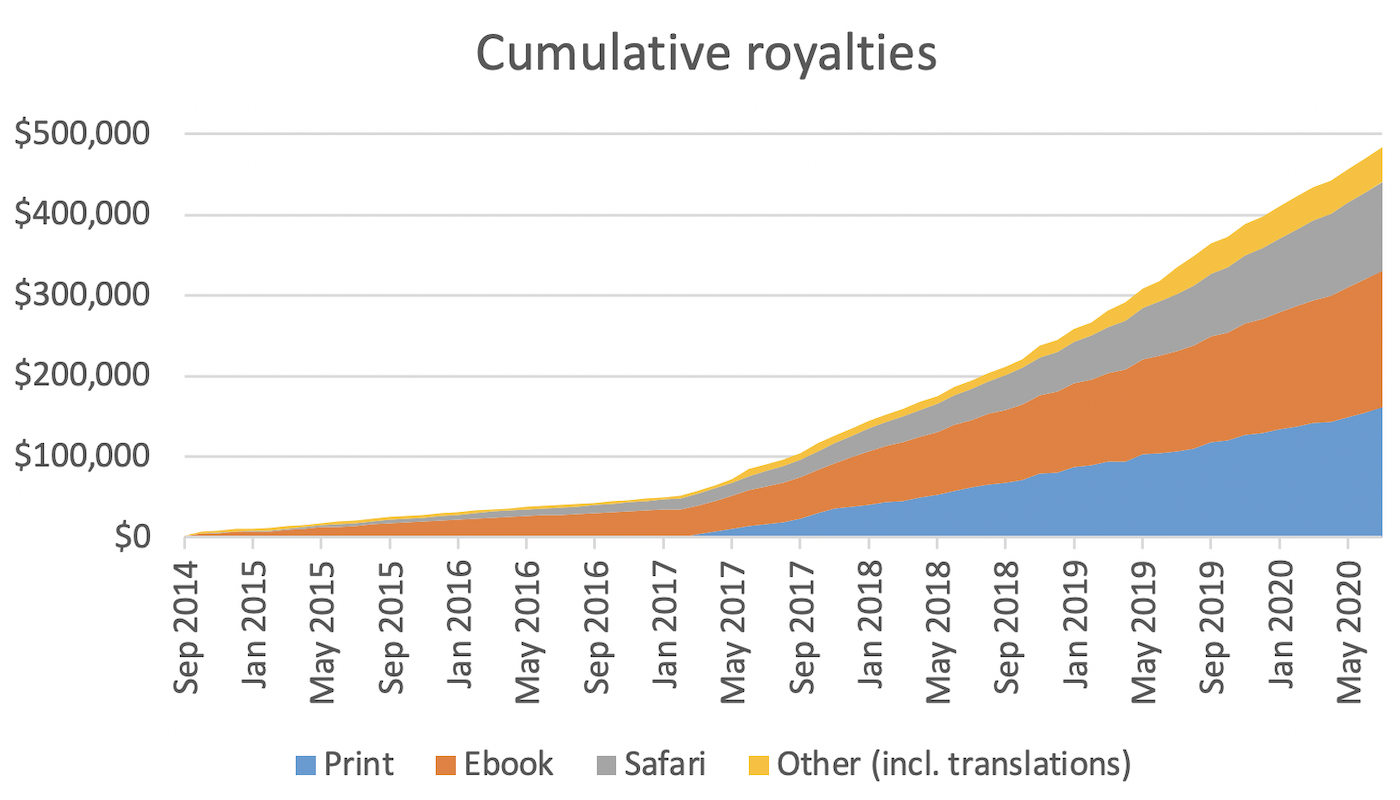

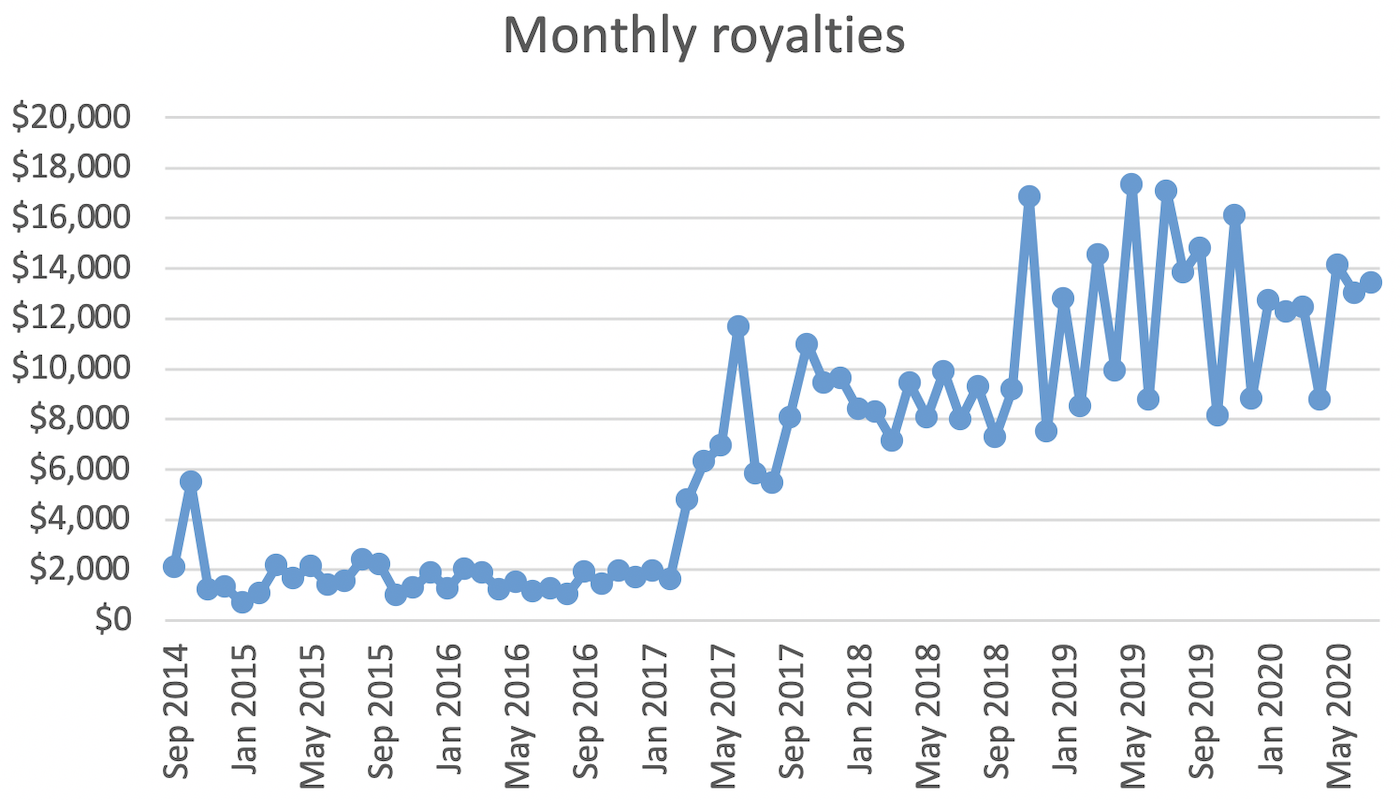

That said, in my case, I am happy to report that writing this book has in retrospect turned out to

be a financially sound decision. These graphs show the royalties I have been paid since the book

first went on sale:

For the first 2½ years the book was in “early release”: during this period I was still writing, and

we released it in unedited form, one chapter at a time, as ebook only. Then in March 2017 the book

was officially published, and the print edition went on sale. Since then, the sales have fluctuated

from month to month, but on average they have stayed remarkably constant. At some point I would

expect the market to become saturated (i.e. most people who were going to buy the book have already

bought it), but that does not seem to have happened yet: indeed, sales noticeably increased in late

2018 (I don’t know why). The x axis ends in July 2020 because from the time of sale, it takes

a couple of months for the money to trickle through the system.

My contract with the publisher specifies that I get 25% of publisher revenue from ebooks, online

access, and licensing, 10% of revenue from print sales, and 5% of revenue from translations. That’s

a percentage of the wholesale price that retailers/distributors pay to the publisher, so it doesn’t

include the retailers’ markup. The figures in this section are the royalties I was paid, after the

retailer and publisher have taken their cut, but before tax.

The total sales since the beginning have been (in US dollars):

- Print: 68,763 copies, $161,549 royalties ($2.35/book)

- Ebook: 33,420 copies, $169,350 royalties ($5.07/book)

- O’Reilly online access (formerly called Safari Books Online): $110,069 royalties

(I don’t get readership numbers for this channel)

- Translations: 5,896 copies, $8,278 royalties ($1.40/book)

- Other licensing and sponsorship: $34,600 royalties

- Total: 108,079 copies, $477,916

A lot of money, but I also put a lot of time into it! I estimate that I spent about 2.5 years of

full-time equivalent work researching and writing the book, spread out over the course of 4 years.

Of that time, I spent one year (2014–15) working full-time on the book without income, while the

rest of the time I worked on the book part-time alongside part-time employment.

Now, in retrospect, it turns out that those 2.5 years were a good investment, because the income

that this work has generated is in the same ballpark as the Silicon Valley software engineering

salary (including stock and benefits) I could have received in the same time if I hadn’t quit

LinkedIn in 2014 to work on the book. But of course I didn’t know that at the time! The royalties

could easily have turned out to be a factor of 10 lower, in which case it would have been

a financially much less compelling proposition.

Beyond the royalties

Part of the success of my book might also be explained by the fact that I put a lot of effort into

promoting it. Since the book went into early release I have given almost 50 talks at

major conferences, plus a bunch of additional invited talks at companies and universities. Every

single talk contained at least a small advertisement for my book. Like a band going on tour to

promote their latest album, I suspect these talks contributed to the book being widely known.

A couple of my blog posts have also been quite popular, and these may also have brought the book to

potential readers’ attention. I have now significantly dialled back my speaking commitments, so

I assume it is mostly spreading via word of mouth

(social media, and readers recommending it to their

colleagues).

The combination of talks and the book have allowed me to establish a significant public presence and

reputation in this field. I now get far more invitations to speak at conferences than I can

realistically accept. Conference talks don’t generate income per se (good industry conferences

generally pay for speakers’ travel and accommodation, but they rarely pay speaking fees), but this

kind of reputation is helpful for getting consulting gigs.

I have only done a bit of consulting (and I now regularly turn down consulting requests from

companies because I’m focussing on my research), but I suspect that in my current position it would

be fairly easy to establish a lucrative consulting and training business, going into companies and

helping them with their data infrastructure problems. That is further financial value that writing

a book can bring: you become recognised as an expert and an authority in an area, and companies will

pay good money to get advice from such experts.

I have focussed a lot on the financial viability of writing a book because I believe that books are

an extremely valuable educational resource (more on this below). I want more people to write books,

and that requires book-writing to be a sustainable activity.

I was able to spend a great deal of time doing background research for my book because I was able to

afford to live without a salary for a year, but many people will not be able to do that. If people

can get paid fairly for creating educational materials,

we will get more and better educational materials.

The economics of book-writing are challenging, and I reiterate that the success of my book is

atypical. However, I also find it heartening that it is possible to make a decent living from

technical writing. Not guaranteed, but possible, and that gives me hope.

A book is accessible education

Besides financial value to the author, there are lots of other good things about writing books.

A book is universally accessible: it is affordable to almost everyone, anywhere in the world. It

is vastly cheaper than a university course or corporate training, and you don’t have to move to

another city to take advantage of it. People in rural areas and developing countries can benefit

equally to those living in the global centres of tech. You can skim it or read it carefully cover to

cover, as you please. You don’t even need an internet connection to use it. Of course it doesn’t

confer all of the benefits of a university education (such as individual feedback, credentials,

professional network, social life), but as a medium for communicating knowledge, a book is almost

unbeatably efficient.

Of course there are also plenty of free resources online: Wikipedia, blog posts, videos, Stack

Overflow, API documentation, research papers, and so on. These are good as reference material for

answering a concrete question that you have (such as “what are the parameters of the function

foo?”), but they are piecemeal fragments that are difficult to assemble into a coherent education.

On the other hand, a good book provides a carefully selected and designed programme of study, and

a narrative that is particularly valuable when you are trying to make sense of a complex topic for

the first time.

Compared to teaching people in person, a book is vastly more scalable. Even if I lecture in my

university’s largest lecture theatre for the rest of my career, I will not get anywhere near

teaching 100,000 people. For individual and small-group teaching, the disparity is greater still.

Yet a book is able to reach such large numbers of people routinely.

Creating more value than you capture

Writing a book is an activity that

creates more value than it captures.

What I mean with this is that the benefits that readers get from it are greater than the price they

paid for the book. To back this up, let’s try roughly estimating the value created by my book.

Of the 100,000 people who have bought my book so far, let’s say that two thirds of them intend to

read it but actually haven’t got round to it yet. Of those who have read it, let’s say that one

third were able to actually apply some of the ideas in the book, and two thirds read it purely out

of interest. So let’s say conservatively that 10% of people who bought the book, that is 10,000

people, have applied it for some useful purpose.

What might such a useful purpose look like? In the case of my book, much of it is about making

architectural decisions regarding data storage. If you get them right, you can build some amazing

systems; if you get them wrong, you have to spend ages painfully digging yourself out of a mess that

you got yourself into.

It’s hard to quantify that, but let’s say that the people who applied ideas from the book avoided

a bad decision that would have taken them one month of engineering time to rectify. (I’d actually

love to claim that the time saving is much higher, but let’s be conservative in our estimates.)

Thus, the 10,000 readers who applied the knowledge freed up an estimated 10,000 months, or 833

years, of engineering time to spend on things that are more useful than digging yourself out of

a mess.

If I spend 2.5 years writing a book, and it saves other people 833 years of time in aggregate, that

is over 300x leverage. If we assume an average engineering salary on the order of $100k, that’s $80m

of value created. Readers have spent approximately $4m buying those 100,000 books, so the value

created is about 20 times greater than the value captured. And this is based on some very

conservative estimates.

There are further ways in which the book creates value. For example, lots of readers have sent me

emails and tweets saying that because they read my book, they did well in a job interview, landing

them their dream job and providing financial security for their family. I don’t know how to measure

that sort of value created, but I think it’s tremendous.

How to be a 10x engineer:

help ten other engineers be twice as good.

Producing high-quality educational materials enables you to be a 300x engineer.

Conclusions

Writing a technical book is not easy, but it is:

- valuable (it helps people be better at their job),

- scalable (large numbers of people can benefit from it),

- accessible (it doesn’t discriminate who can benefit), and

- economically viable (it is possible to generate a reasonable level of income from it).

It would be interesting to compare it to working on open source software, another activity that can

have significant positive impact but is

difficult to get paid for.

I don’t have a strong opinion on this at the moment.

On the downside, writing a book is really hard, at least if you want to do it well. For me it was

about the same level of difficulty as building and selling a

startup (YMMV), that is to say, involving

multiple existential crises. The writing process was not good for my mental health. For that reason

I haven’t rushed into writing another book: the scars from writing the first one are still too

fresh. But the scars gradually do fade, and I’m hoping (perhaps naively) that it might be easier

next time.

On balance, I do think that writing a technical book is worth it. The feeling of knowing that you

have helped a lot of people is gratifying. The personal growth that comes from taking on such

a challenge is also considerable. And there is no better way to learn something in depth than by

explaining it to others.

In my next post I will provide some advice on writing and publishing from my experience so far.

If you found this post useful, please

support me on Patreon

so that I can write more like it!

To get notified when I write something new,

follow me on Bluesky or

Mastodon,

or enter your email address:

I won't give your address to anyone else, won't send you any spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.