Harm reduction for cryptographic backdoors

Martin Kleppmann

14th Workshop on Hot Topics in Privacy Enhancing Technologies (HotPETs),

Online,

July 2021.

The Problem

The pattern has been repeated ad nauseam: law enforcement officials complain that end-to-end

encryption makes their work difficult, and campaign for weakening it; information security

professionals respond with an outcry, saying we must never deliberately weaken security. The

arguments have been rehearsed many times ever since

the crypto wars of the 1990s, and I will not rehash them. Instead, I would like to outline

a proposal for a compromise.

To some, the mere idea of compromise on this matter is tantamount to treason; they say “cryptography

is just math, you can’t ban math” to argue against any sort of regulation of cryptography. I believe

that such a reductionist stance is unproductive: it ignores the fact that software systems are still

subject to laws. The people maintaining the software, its users, the company hosting the servers

that support the software, and the companies providing the app stores through which the software is

distributed are all subject to the laws of the countries in which they live or operate. We can and

should campaign against laws and proposals that we think are unreasonable, but ignoring them

entirely is not going to work long-term, especially when there is public support for law

enforcement’s side of the story.

At present, law enforcement agencies (LEAs) are pushed to use zero-day exploits or

ghost user attacks to conduct

surveillance on end-to-end encrypted systems. These tools are problematic since they provide no

accountability to ensure that they are being used in a lawful way, making them harmful to security

overall. It would be better to take a harm reduction approach: to have an explicit backdoor

mechanism that ensures accountability, and which has safeguards to prevent abuse. In particular, it

should not be susceptible to undetectable mass surveillance, and it should ensure that any

surveillance is legal.

A Proposal

I believe the following proposal achieves this goal. It is fairly simple, but I have not seen it

described previously.

A provider of a communication service (say, Facebook in the case of WhatsApp) maintains

a transparency log, similar to Certificate Transparency,

containing all of the law enforcement intercept orders (warrants, subpoenas) it has received and

accepted. The log is public. Each log entry contains a few publicly readable fields: the

jurisdiction of the warrant, a code indicating the reason (terrorism, child sexual abuse, etc),

validity start and end date, and a cryptographic commitment to a single device ID that is the target

of the warrant. Thus, anybody can see how many warrants are being issued in which jurisdiction and

for which reason, but not who their targets are. Auditors (e.g. ACLU, EFF) track the log and report

summary statistics to the public.

To intercept a device’s communication, the service provider must first add the entry to the log,

then send a message to the device that reveals the device ID in the commitment, and a proof that the

entry is included in the log. The software on the user’s device checks whether the log entry is for

its own device ID, and if it is valid, the software silently uploads a cleartext copy of the

requested data to a server accessible to the appropriate LEA, and this process continues until the

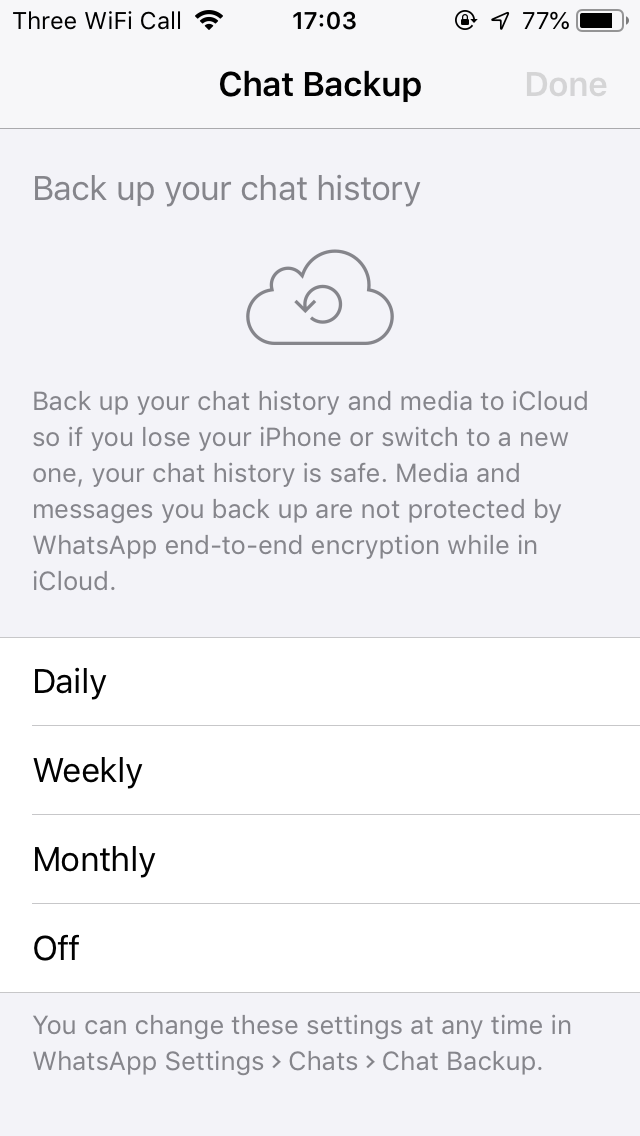

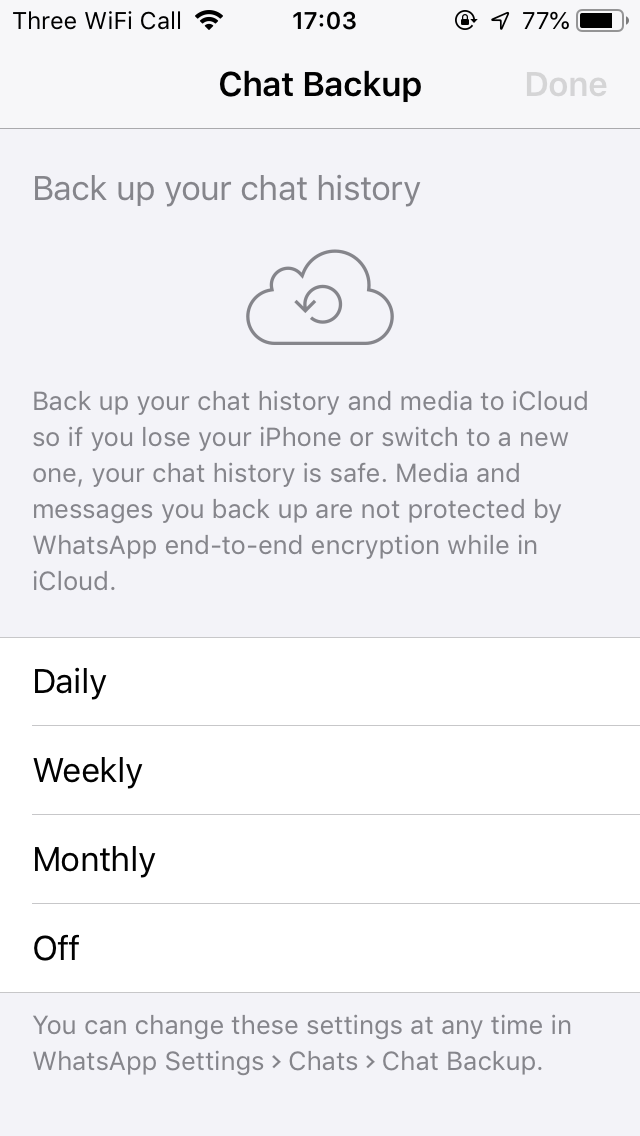

expiry date. This is essentially identical to the cloud backup feature that is already built into

otherwise encrypted messaging apps such as WhatsApp and iMessage, which

upload an unencrypted copy of the user’s messages to a cloud service;

the backdoor merely silently enables this backup if it had been disabled by the user.

Additionally, in each jurisdiction there is a trusted oversight board. The service provider must

give the oversight board in the appropriate jurisdiction a copy of every warrant it accepts, and

reveal to it the target of the corresponding log entry. The board checks that each log entry has

a corresponding warrant, that the warrant is genuine and legal, and that it targets a specifically

named individual suspected of a serious crime. If the board determines that the system is being

abused, it has legal powers to stop the abuse.

Discussion

Unlike key escrow and other backdoor proposals, this approach ensures the backdoor cannot be used

without leaving a public audit trail, and it does not involve any weakening of the cryptographic

protocols. There is no single “golden master key” that can silently decrypt all communications,

avoiding the problem of how such a key would be managed. Since a single log entry can only target

a single device, the number of devices intercepted is public, and thus any attempts at conducting

mass surveillance through this system would immediately be noticed and subject to public debate.

To avoid publishing exact numbers, the service provider can include fake entries in the log,

allowing over-reporting but not under-reporting of numbers. To avoid leaking timing of when exactly

warrants are issued, the service provider can publish a mixture of real warrants and fake log

entries on a pre-set schedule (similarly to cover traffic in

some anonymity networks).

Aside from any delays due to such a pre-set schedule, this proposal does not introduce additional

delays into the existing legal process for warrants or subpoenas, which is useful for time-sensitive

investigations.

It is important for users of a communication system to know which countries are granted interception

capabilities, since activities that are legal in one country may not be in another country (e.g.

being gay or criticising the government), and countries differ in the degree to which they uphold

the rule of law. The proposed scheme forces service providers to be explicit and public about the

jurisdictions in which they will accept warrants.

The proposed scheme is simple, allowing it to be understood by people who are not technical experts.

It uses only basic cryptography. Since many communication apps already have a backup feature, and

users are likely to want to keep such a feature, adding the backdoor requires very little additional

client-side code in many cases.

Figure 1: WhatsApp encourages the user to enable backups, causing an unencrypted copy of the user's messages to be uploaded to a server.

Law enforcement gains access to any data that is stored on the targeted user’s devices at the point

in time when the warrant takes effect (including message history if it is stored), but any data that

has been deleted from the targeted user’s devices is gone. If the system provides forward secrecy,

the LEA does not gain the ability to retroactively decrypt deleted messages. I believe this is

a reasonable compromise, since it is the same information as a LEA would gain if it physically

seized the device and unlocked it.

A limitation of this design is that it assumes the messaging software is able to run on the target

device and is able to receive and process messages. In cases where the device has no network

connectivity, it might not be possible to remotely activate the backdoor, so the LEA would need to

gain physical access to the device and unlock it instead.

The fact that an app contains a backdoor would be publicly known. Would this mean criminals simply

move to another app? Probably not: how is a gangster to know that the alternative app isn’t

secretly operated by the FBI? And installing a custom

build of an open source messaging app, after having carefully reviewed its code for weaknesses,

requires deeper technical skills than most criminals have. Moreover, there are network effects:

co-conspirators need to be convinced to use the same app.

The proposed scheme relies on a trusted oversight board to check the validity of warrants. There is

a risk of the oversight board being too docile (regulatory capture), which is mitigated by making

the number of warrants public. If civil liberties organisations believe that the number of people

being surveilled is too high, they can instigate public debate and put pressure on the oversight

board to be stricter.

Would this scheme be acceptable to LEAs? In a

2018 article, two GCHQ technical directors set out principles that they

think backdoors should satisfy. They explicitly do not want key escrow or bulk decryption

capabilities, and they do want to provide transparency about the number of people surveilled, in

order to assure the public that the backdoor is only used on a small number of specifically named

suspects. This is exactly what my proposal provides.

Conclusion

LEAs have a legitimate need for targeted surveillance to investigate crime. This does not mean we

should bow to every LEA wish, but we cannot dismiss them wholesale either. I fear that if the

information security community categorically refuses to engage with the need for targeted

surveillance, we will end up with poorly conceived legal measures being imposed, to the detriment of

everybody’s security. I believe it is better to engage constructively with law enforcement and to

work together towards system designs that balance investigative capabilities with protection of the

civil liberties that form the foundation of a democratic society.